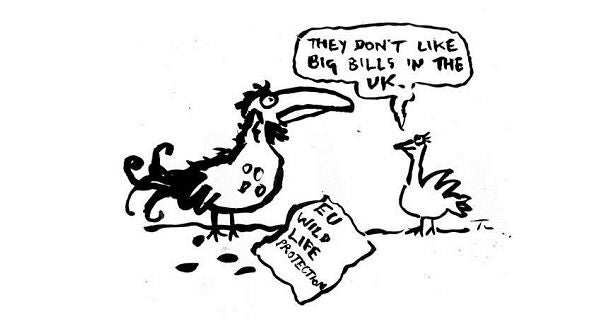

If you love wildlife, think twice before contemplating voting to leave the EU

The strongest protection for nature in the UK comes straight from Europe

Starting to hate the European Union? Feeling swayed by the clamour about unrestricted immigration and unreasonable demands for huge new budget contributions, etc? Well if you are, and if you feel you might vote for us to leave in a 2017 referendum (should the Tories win the next election), you need to do some serious thinking – if you also love Britain’s countryside and wildlife.

For it is remarkably little appreciated by the public at large, but the strongest protection for nature in the UK itself comes straight from Europe, and withdrawal from the EU would put that at risk.

One of the EU’s outstanding achievements has been the creation of a vast body of environmental law looking after the natural world, which is far tougher than any such legislation we have passed ourselves.

These laws, framed in what Brussels terms as directives, and subsequently transposed into British regulations, cover everything from river pollution to air quality, from waste disposal to sewage treatment, and over the past 40 years they have forced the UK to clean up its environmental act substantially, in a way that would never have happened had we remained outside the EU.

Perhaps the clearest example of the benefits European legislation offers the environment in Britain comes in the form of the EU wildlife laws, which are enshrined in two closely related directives, the 1979 Birds Directive and the 1992 Habitats Directive, implemented in British law through what are known as the Habitats Regulations. Under these, a wildlife site – an estuary, a mountain, a forest, an island – can be designated a Special Protection Area, or SPA, under the Birds Directive, or a Special Area of Conservation, or SAC, under the Habitats equivalent, and if that happens, the site in question suddenly has a formidable shield around it.

It becomes, if not quite impossible, extremely difficult for inappropriate development to take place on it, and far more difficult than it would be had the site been notified under home-grown, much weaker, designations – as a Site of Special Scientific Interest, say, or as part of an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, or even as part of a National Park.

“EU laws now underpin nature conservation in Britain, providing the highest level of protection for the most important sites and species,” says Martin Harper, conservation director of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds.

With SPAs and SACs, any developer has to demonstrate there are no alternative ways of meeting the project’s objectives; that there are “imperative reasons of overriding public interest” for carrying out the project in the first place; and that compensation will be provided, usually in the form of land equivalent to the habitat the project has destroyed.

These are pretty tough tests to pass, and indeed, in recent years they have stopped in their tracks some proposed big developments which many people regarded as immensely damaging.

One such was the plan for a colossal container port at Dibden Bay on the edge of the New Forest, which would have contained more than a mile of shipping berths in one of the largest dock areas in Europe, generating more than 3,000 heavy lorry journeys a day through the eastern side of the forest.

Another was a wind farm of 181 turbines planned for the Isle of Lewis in the Hebrides, which would have devastated a wildlife-rich landscape.

These rejections, of course, greatly angered the developers, and in 2011 the Chancellor, George Osborne, showed his own impatience with the Habitats Regulations, complaining that they placed “ridiculous costs” on British business.

He demanded a review by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra). Defra reported four months later – bravely, you might think – that the regulations were “working well” and were “not a burden on business in most cases.”

Mr Osborne, and others, would no doubt like to tear the regulations up; but of course he cannot, as we are an EU member state. But were we to withdraw – and this is the point – there would be nothing to stop him persuading the Cabinet to rescind them, or at least, alter them so that their effectiveness would be neutered.

And it is not just wildlife sites which European law covers. One of the most important of recent EU measures has been the Water Framework Directive, which is driving a wholesale restoration of the ecological quality of rivers and lakes; just as another law, the Bathing Waters Directive, forced British water companies in the 1990s to spend billions of pounds cleaning up the sewage they pumped into the sea.

The point, ultimately is a simple one. If you’re thinking of voting for EU withdrawal but you also cherish our environment, our countryside and our wildlife, be careful what you wish for.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies