Not fit for purpose: why this Bill is unworkable, ill-considered, and an affront to our privacy

If a very similar Bill was rejected in 2009, why should the Government think that it will be widely accepted now? They should go back to the drawing board and start again

Today, the final report of the pre-legislative scrutiny committee on the Government’s draft Communications Data Bill is published. Together with the Intelligence and Security Committee Report, also published today, it does not make easy reading for the Government. The Bill is not fit for purpose. The issues that it attempts to deal with are real enough. The Government should accept the two committees’ reports as just criticism.

For the past six months I, together with eleven other members of the Commons and the Lords, have sat on the scrutiny committee. We have taken evidence from the Home Secretary and her officials, technical experts, service providers and civil liberties campaigners, as well as over 100 individual written submissions from members of the public.

A different world

The case for legislation is this: before the internet, when we all communicated by phone, BT or whoever provided your phone line had a business case for keeping a record of your phone calls. They billed you according to how many calls you had made that month. Therefore if someone was suspected of a crime, the police had a way of checking that person’s recent communications history.

Online providers, the companies that provide your internet or the email service you use, have no need to keep any of this. BT don’t care what websites you are on or who you send emails to, just that you pay the flat bill at the end of the month. The Home Office say that this means there is an ever growing capacity gap in the information available to the authorities to help convict criminals. The Communications Data Bill is the Government’s attempt to plug that gap.

In essence they seek to address this by legislating to enable the Government to pay providers to keep the extra information that law enforcement agencies say they need. This is the same proposal put forward by the Labour Government in 2009, with one difference: the information will not be stored centrally, but instead will be accessible via a “filter”, a search engine which can dip into each private company’s store of information.

In 2009 the Government consulted on the plans and decided that, on balance, this was not a proportionate measure for dealing with the problem. Predictably, the Joint Committee heard that the problems identified three years ago around privacy and proportionality have not been addressed in the current Bill.

In particular Clause 1 of the draft Bill, which details what information the Home Secretary can require companies to keep and which authorities can access it, is drawn far too wide. It is essentially an enabling clause, allowing the Home Secretary to decide and revise these requirements at a later date.

When dealing with an issue which raises so many questions around privacy it is essential that the legislation be more prescriptive. It should be for Parliament to decide if other agencies are to be added at a later date. The Joint Committee Report also questions whether the case has been made for requiring companies to keep weblogs, records of which websites their customers have visited.

The central area of public concern is one of privacy. People are worried that if all this information is kept and is available to public officials then some of those officials will either lose it somehow or will be tempted to sell it on for profit, probably to a tabloid newspaper journalist. Of all the written submissions we received from individuals not one was in support of the Bill. The Joint Committee has made several recommendations on tightening up the security of data, the penalties for abuse and the oversight of the whole structure.

There is a good case for a strengthened role for the Information Commissioner and also for creating a new offence of wilful or reckless use of communications data. If the Bill is to go ahead it is essential that the public has confidence in the new system.

Even if we accept the case that the plans will go some way to plug the information gap, and will do so in a secure manner, the Home Office have clearly failed to make the “business case” for the Bill. It is costed at £1.8bn, claims benefits of up to £6bn, and the Home Office say it will enable access to 85% of communications data rather than 75%. The Joint Committee Report is categorical: “The Home Office’s cost estimates are not robust… The figure for estimated benefits is even less reliable than that for costs, and the estimated net benefit figure is fanciful and misleading”.

In other words these figures seem to have been plucked out of thin air. In 2009 the plans were costed at £18bn. Even at £1.8bn the Bill costs more than the £1.5bn the Government will save in this Parliament by sacking police officers. It is reasonable to accept that this Bill will catch criminals but to wonder if the budget could be better spent. Without any evidence to support the Home Office’s costings it is impossible to weigh that decision.

Unworkable

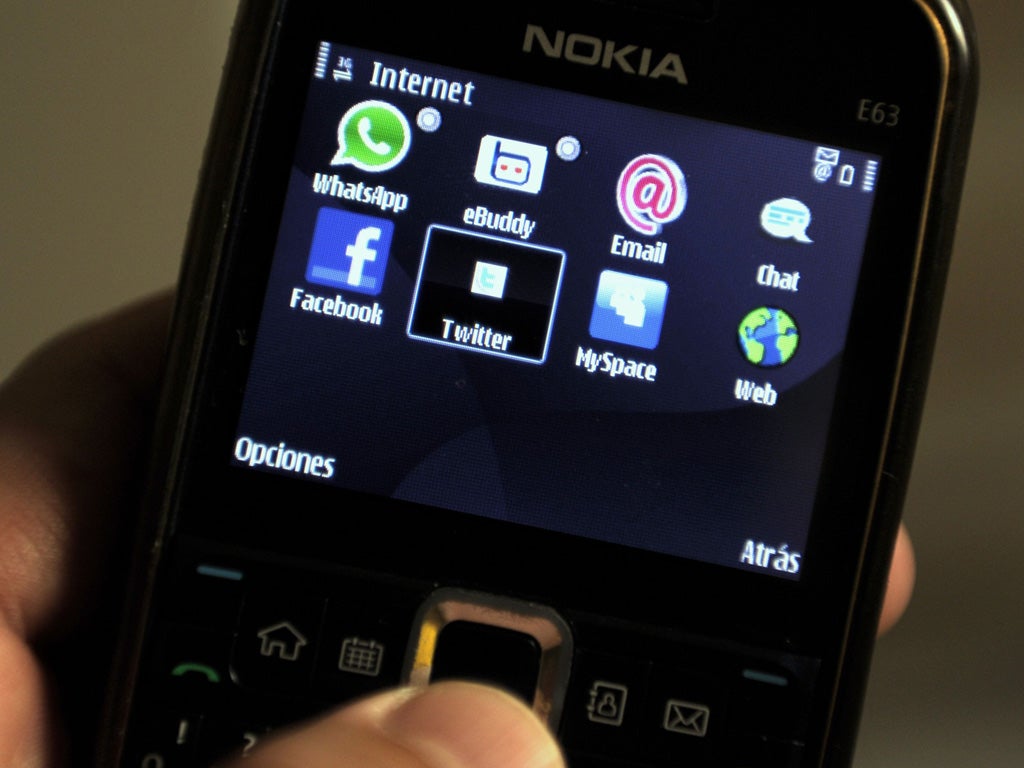

Finally – will the Bill work? The Home Office and the law enforcement agencies have been cagey about giving too much detail about what their information gaps are, and reasonably so. We wouldn’t expect them to publicly declare how criminals can evade the law. But it does invite the suspicion that the powers of this Bill are being overplayed. Already it is possible to think of communications technologies that wouldn’t be captured by this Bill – draft emails, interactive computer games and embedded content on social networks are just some of the examples put to the Committee.

The reasonable conclusion is that yes, this legislation will lead to convictions, but for pretty low level crime – “Incompetent criminals and accidental anarchists” as the Information Commissioner put it. Serious and systematic law breakers who have the motivation and resources to evade the police will surely find this Bill does little to hinder them.

The Home Secretary has defended this Bill in the past fortnight by howling about terrorists and paedophiles. But she also gave the example of the two police officers who were killed in Manchester earlier this year. The shootings, she said, “show the extent of the problems caused by criminals”. Well, yes, they do, but it’s hard to see how the police having a better record of the gunman’s internet usage would have stopped him shooting two officers on a seemingly routine call. The use of the case as an example is a pretty offensive trick for the Home Secretary to use.

And therein lies the problem. The Tories and the Lib Dems are trying to push through legislation which both parties shrilly opposed in 2009. The Home Secretary hasn’t found the answers to overcome the objections that persuaded the then Labour Government not to proceed with similar legislation. Almost every witness to the Joint Committee, from civil liberties groups to service providers, complained of a lack of clarity from the Home Office about what is being proposed and a lack of consultation over whether it would work.

The privacy concerns of the wider public have not been addressed. If the Home Secretary is right that criminals are going free because this legislation hasn’t passed yet, then it is her responsibility to urgently work with the industry to put together a Bill that will actually do what it sets out to, and that will address people’s legitimate concerns about their personal privacy. The present draft Bill isn’t it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies