Power to the people? Don't make me laugh

It's one of the fundamental truths of modern life that most of the decisions that affect us are taken by people over whom we have not the faintest control

It has been a fascinating few days for anyone interested in the nature of power as exercised in the 21st century, the identities of those who exercise it, and the relationship between the exercisers and the people at the bottom of the hierarchical pyramids that these behemoths command. Item one in this inquiry was the release of Forbes magazine's annual list of the most powerful individuals in the world – an eye-catching roster that included such temporal and spiritual luminaries as Vladimir Putin (at No 1), His Holiness Pope Francis (4), Angela Merkel (5) and Rupert Murdoch (a rather feeble 33), and which, to the experienced power-decoder, might be thought to have seriously missed the point.

For power, as modern novelists long ago discovered to their cost, is no longer a straightforward business, a simple matter of decision and response, the bringing together of resources and influence to achieve an immediate end. Take, for example, David Cameron, who appears at 11 on the Forbes list. To be sure, Mr Cameron is the chief minister of a top-level sovereign state and yet, in all kinds of areas, ranging from foreign affairs, where there are potent allies to be appeased, to economic strategy and even domestic policy, where there are coalition partners forever breathing down his neck, his hands are tied. The power that our man in No 10 wields is, you see, formal and, therefore, in the complicated world we now inhabit, illusory or at any rate seriously contested. The really sharp operators, it might be argued, are oil traders and commodity brokers, hunkered down in the silos of the American Midwest, whose identities are known only to a small number of insiders.

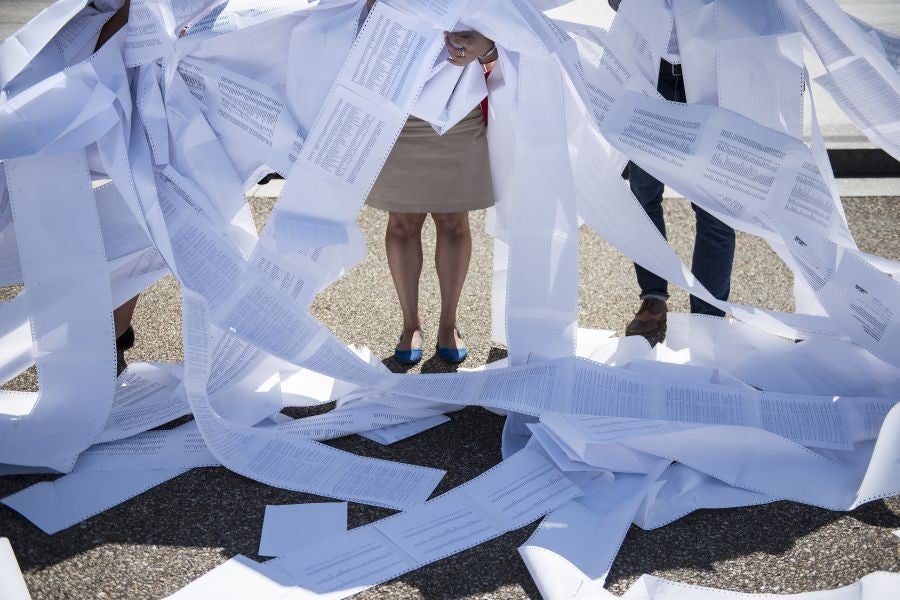

The second item in this inquiry was the number of instances of ordinary people – a majority of ordinary people, so far as one could tell – appearing to want something that, it seems pretty clear, they will not be able to get. Thus Tuesday's opinion poll on the price-raising strategies pursued by the Big Six energy firms showed that 80 per cent of the public wants bills to be frozen but, for all Ed Miliband's spirited interventions, it would be a very sanguine pundit who believed that this was going to happen. On the same day, coincidentally enough, Norfolk County Council's cabinet decided to continue with a controversial incinerator recently constructed in the King's Lynn area. Recently, 67,000 local inhabitants had signed a petition against this fiery furnace; last spring's local elections saw the voting out of many a politician who had supported it; and yet, six months later, the council still voted 40-38 for its retention.

Why can't people – majorities of people – have want they want, whether it is a form of energy supply that doesn't involve the creaming off of enormous profits or the removal of an incinerator from the north Norfolk plain? The answer to question one, naturally, is that this is a highly complex economic issue where popular sentiment counts for very little. The answer to question two is that local councillors, like Members of Parliament, are representatives, not delegates, and that electors trust them, or are supposed to trust them, to use their judgement in pursuit of what they believe to be the common good.

But none of this, alas, disguises what we know to be one of the fundamental truths of modern life, which is that we live not in a democracy but an oligarchy where most of the decisions that affect us are taken by people who are rarely subject to the checks and restraints that inhibit the ordinary citizen's passage through life and over whom we have not the faintest control.

By chance, sitting in the audience at last weekend's inaugural Gibraltar Literary Festival, I found myself listening to what very soon revealed itself as a defence of oligarchy. It was delivered by Mary-Jo Jacobi, whom long-term observers of the US scene will remember as a special adviser to Ronald Reagan and as George Bush Snr's Assistant Secretary of Commerce. Ms Jacobi currently ornaments half-a-dozen boardrooms on both sides of the Atlantic and recently joined the Prime Minister's advisory committee on business appointments. An immensely personable and forceful speaker, she took as her subject "Gibraltar in the global economy", and the thrust of her argument will be horribly familiar to anyone who browses the think-pieces in The Economist or the business pages of right-wing newspapers.

And so here we were, Ms Jacobi declared, smack in the middle of a desperately complicated world, where even the Federal Reserve has trouble understanding what is going on, and politicians are marooned in a kind of economic swamp where only technocrats have the answer and governments can hope to ensure prosperity for their citizens only if they allow entrepreneurs, frackers, and free-traders to let rip with minimal interference. As for Gibraltar, a selection of whose financial services professionals sat raptly before her, its advantages to the incoming foreign businessman were well-nigh limitless: cheap labour just across the border in Spain, a government keen on inward investment, low tax rates and a decent jurisdiction. A fiscal jam pot, in other words, ripe to be exploited and have money made out of it, and we should all straightaway jump in.

The interesting – and rather frightening – aspect of this free-market love-in was the conviction of the attitudes on display. A British captain of industry who embarks on this kind of thing in front of a paying audience generally makes some kind of faint obeisance to the idea of communal will and democratic imperatives. To Ms Jacobi, on the other hand, the economic fate of the world clearly depended on a small collection of rich people being allowed to do what they liked with very few questions asked. In the end, greatly daring – for Ms J is not to be trifled with – I asked a question: did the speaker sympathise with the frustrations of the millions of ordinary people who believed that they had no control over their lives and that the world was increasingly run by a collection of oligarchs so powerful that no government or international organisation had the ability to rein them in?

Ms Jacobi did sympathise; she sympathised very much. But her line here seemed to be that there would always be powerful, untrammelled people at large in the world, and there wasn't a great deal you could do about it. Worse, the democratic institutions of the West, established in a less complex time, had lost the administrative nous necessary to run the 21st-century economy. If we let the oligarchs get on with evading their tax demands and digging up the Dakota shale for gas, then at least a few crumbs from their exorbitantly laden table might eventually descend to the rest of us at floor level.

It scarcely needs saying that all this offered a salutary lesson, though not perhaps the one that President Reagan's former special adviser imagined she was preaching. The real issue, I decided, as the Gibraltar lawyers clapped and Ms J sped off to the airport, is not left versus right, or statism versus bonfires of red tape, or sovereignty versus Europe: it is accountability.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies