Savile's escape has put our public institutions on trial

From his own relatives to BBC executives and charities, those who could have stopped the abuse had incentives not to ask questions

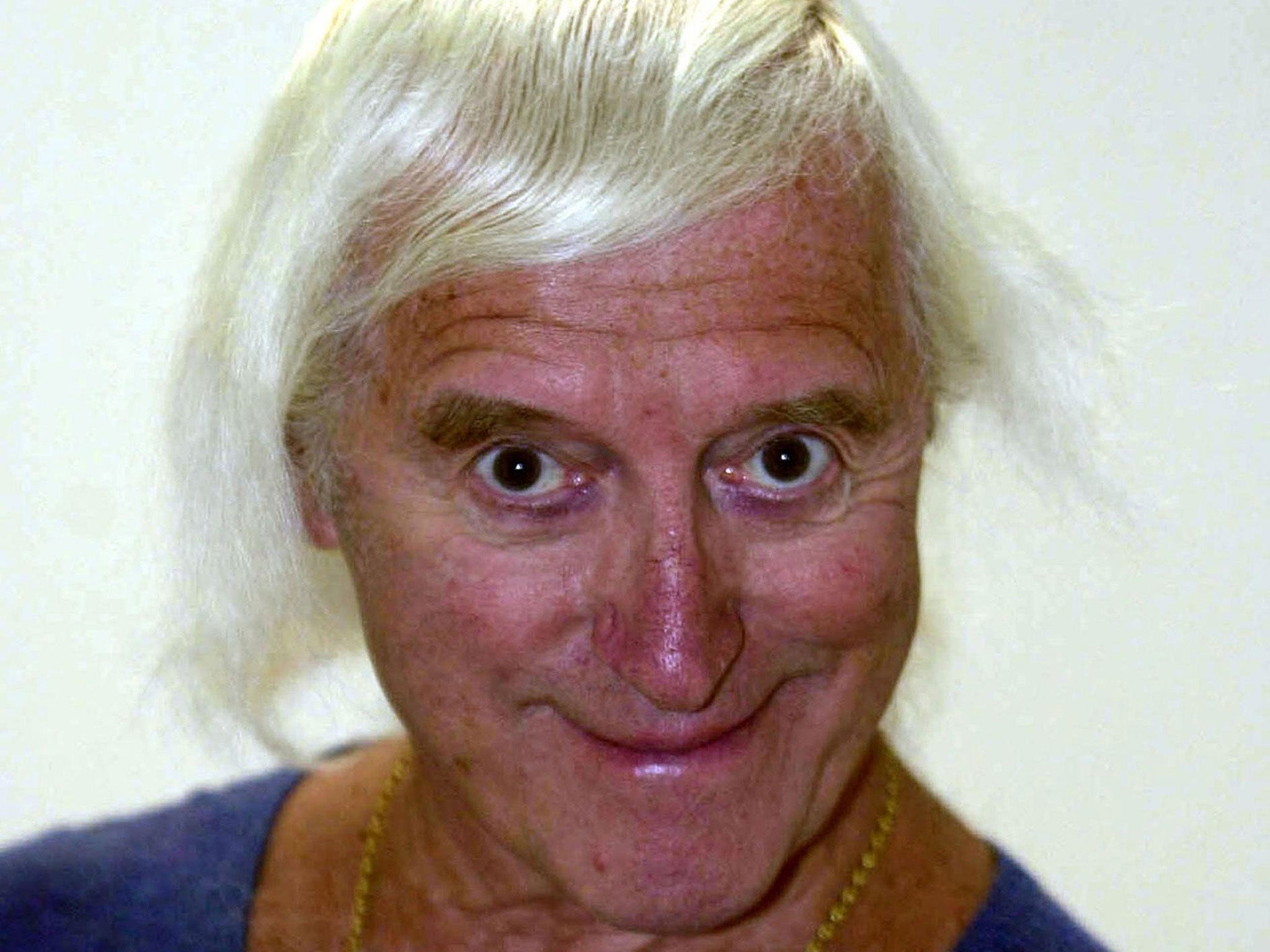

When I was a young man, I had my own encounter with Jimmy Savile. It was not sexual, but involved the kind of abuse that lies at the heart of the scandal which has rebranded the "wacky national treasure" as one of Britain's "most prolific sex offenders".

I was a young reporter on the Yorkshire Post in the days when Savile had just made the transition from a Radio 1 DJ to the presenter of one of Britain's most popular television shows, Jim'll Fix It. He was, consequently, a major figure in his home town of Leeds where, after some charity fundraising event, I interviewed him. Savile was a man with two faces; his flamboyant public bonhomie could give way in private to something quite threatening. I asked him, probably naively, whether there wasn't an ambiguity to his image as the man who raised £40m for charity, since it obviously gave quite a boost to his television career.

"Did you know I'm good friends with Gordon Linacre?" he inquired coldly. (Linacre was the chairman of the board of Yorkshire Post Newspapers). "I don't think he'd like it if he knew one of his reporters was asking questions like that."

Jimmy Savile was a good friend, by his own account, of all sorts of people including Margaret Thatcher, Prince Charles and the Pope. On the side, we now know, he was sexually abusing more than 400 people, most of them girls aged between 13 and 16, and committing 200 crimes, including 31 rapes. But considering the way he used his fame it is hardly surprising that no underage teenager felt anyone would believe her word against his.

A few tried. A 15-year-old dancer on Top of the Pops went to the police in 1971. But when detectives dismissed her claims as fantasy she committed suicide, leaving behind a diary detailing claims of how she had been "used". Later a detective reported allegations – made by a nurse at Stoke Mandeville Hospital – that Savile was abusing patients. His commanding officer told him there was not enough evidence to proceed against a celebrity of Savile's stature.

But some were believed and quietened. Savile's niece complained to her grandmother when her uncle put his hand inside her knickers. Don't make a fuss, she was told, it's only Uncle Jimmy. Grandma's comfortable lifestyle depended upon Savile's largesse. It was a pattern that others replicated – colleagues in the music industry, BBC producers and executives, charities and hospitals all had an investment in not asking too many questions.

There was something else. Social attitudes were different then in so many ways. The nature and scale of child abuse were not understood. Those were the days when the National Council for Civil Liberties, staffed by Patricia Hewitt and Harriet Harman, allowed the Paedophile Information Exchange to be an affiliate, despite its members lobbying for the age of consent to be lowered. It was a time when mainstream television comedy consisted of a leering Benny Hill, in his dirty old man raincoat, chasing girls in short skirts round a tree. And Jimmy Savile could put his hand up a teenager's skirt on live TV as he introduced the next act on Top of the Pops. He hid behind the truth to con the entire nation.

The Seventies and Eighties were still, for all the social revolution of the Sixties, an age of deference. As a boy, I was once punished by a priest teacher who made me lie spread-eagled on the floor. He then walked over my fingers. When I told my mother of this decades later she was astonished and asked why I had not told her at the time.

She had forgotten that in those days the axis of relationship was different. All adults – teachers, policemen, priests and parents – were authority figures who shared a common view of the world. If you told your father you'd been disciplined at school you would quite likely be punished again for it at home. But all that has gone. Today a parent is on the child's side, and is far more likely to march up to school to punch the teacher. Deference and unearned authority have been replaced by a culture of suspicion.

There are good and bad sides to this. We now know more about the compulsive behaviour of child abusers – though, even now, young victims are sometimes still not believed, as the abused girls of Rochdale know to their cost. We are unforgiving of those such as the Catholic church who seek to cover-up such horrible crimes, though recent years have also taught us that press, politicians and police can be as corrupt as priests. We have put in place all manner of child protection measures, to a degree where we sometimes impoverish relationships between adults and children; many teachers are now afraid of cuddling a distressed child. Everywhere, process and procedure have replaced leadership and action, which is why the Pollard Report found the BBC's "rigid management" systems were "completely incapable" of dealing with the fallout of the Savile crisis.

Yet for all the media focus on the BBC, we now discover that twice as many of Savile's assaults took place in hospitals as in TV or radio studios. And the police investigated him six times but failed ever to find a way to curb his abusive behaviour. Jimmy Savile has escaped trial, but a wide range of our public institutions have not, and they have been found wanting.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies