The silent epidemic of head injury in young offenders

New research suggests that a childhood brain injury could increase the likelihood of someone committing a violent crime.

A few years ago I arranged a study visit to a prison.

While I was there one of the inmates asked me why, when he pressed a part of his head, he experienced odd visual sensations.

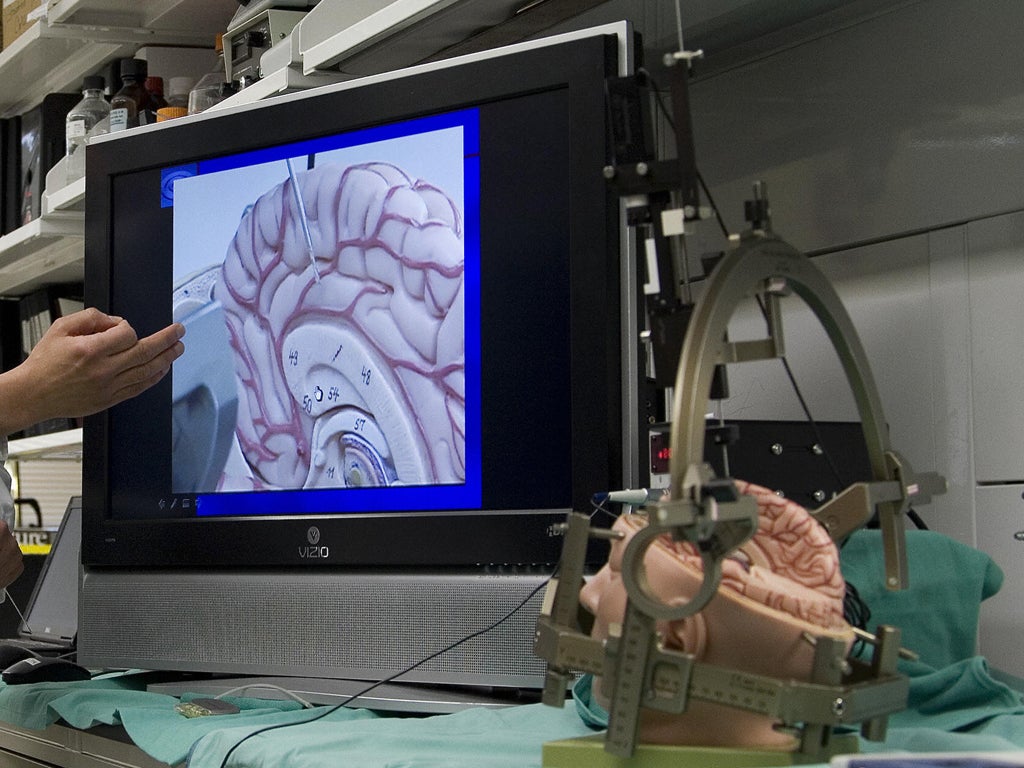

I noticed an area of his shaved head where it looked as though there was a piece of skull missing, over the sensory motor cortex. I advised him to stop pressing the area. It is likely that a part of his skull was removed to decrease pressure on the brain, probably after a traumatic injury, but a replacement titanium plate hadn’t been inserted. It led me to wonder what the true scale of head injury was in the prison population – and whether their needs were being met.

Think about your brain for a moment. As you read this billions of neurons are at work, making connections and transmitting data in processes of breathtaking complexity. While awe-inspiring, the brain is also highly vulnerable, particularly during development.

It’s not until our early twenties that our brains are fully developed. The process is particularly dynamic across the teenage years and continues beyond the age at which government may declare “adulthood” to have begun. During adolescence and young adulthood, the brain’s grey matter – the outermost layer of brain tissue – matures by discarding or strengthening connections. The brain gets “sculpted” into being. This is a time of turmoil, both neurologically and socially, when the risk of receiving a traumatic brain injury is heightened, especially for boys and men, through falls, sports or road traffic incidents.

Thankfully most injuries are mild, but with more injuries there may be a cumulative impact leading to ongoing problems. In a bar on a Saturday night out, someone may be punched, fall to the ground, bang their head on a pavement and be unconscious for minutes, hours or days. Depending on the severity, there could be ongoing neurological consequences from poor concentration and memory, to mental health problems, to problems controlling impulses and anger. While marked changes in behaviour may follow, often these injuries may not be detected or treated.

Today sees the launch of a report I have written on the implications of brain injury for criminal justice, which was commissioned by Barrow Cadbury Trust for the Transition to Adulthood Alliance, a coalition of 12 charities working to evidence and promote effective approaches for young people in the transition into adulthood throughout criminal justice.

Our work and other research conducted internationally points to the fact that a childhood brain injury increases the likelihood of someone committing a violent crime by adulthood. Shockingly, around 60% of young adult offenders report having suffered brain injuries, between three and six times as many as in the population at large. The evidence is that where there is treatment after injury there is less risk of violence. When untreated though, they seem to magnify other problems, from hyperactivitity to drug misuse.

This is not to excuse anti-social behaviour, but explain how brain injuries can becomes a catalyst for it. There are thousands of young people who have suffered neurological damage, who did not receive necessary support – to stay in school, to manage their emotions – and have been left vulnerable to being drawn into criminal activity.

The way we treat young people with brain injuries goes beyond criminal justice – and I’ve explored the issue alongside Dr Nathan Hughes of the University of Birmingham in a report for the Office of the Childrens’ Commissioner also released this week. But criminal justice is the coalface where these challenges are most acutely felt. Indeed, that report also calls into question whether the criminal justice process treats young people with neurodisability fairly.

So what we do to treat this silent epidemic? How do we halt the conveyer belt through our courts, Young Offenders Institutes and prisons, of young people who need not have been drawn into crime?

We need early intervention, effectively managing brain injuries immediately after incidents, monitoring and treating ongoing symptoms. Schools have a part to play here. Secondly, we need widespread recognition of the issue among criminal justice professionals, alongside effective assessment and screening, both in custody and in the community. It should be standard practice to screen young people for brain injuries pre-sentencing.

This should be an example of evidence-based policymaking. Without a firm grounding in the science and in lived experiences, we can’t make criminal justice work for young people or for society at large. We know that allowing young adults to be drawn into the criminal justice process has a huge cost; to the Treasury, to communities and to individuals. We know that the chances of young people reoffending is actually increased by contact with criminal justice agencies.

We know with the right interventions, young people with brain injuries can lead full lives as valued members of society. We need to start making connections.

Prof Huw Williams is an Associate Professor of Clinical Neuropsychology and Co-Director of the Centre for Clinical Neuropsychology Research, University of Exeter.

You can follow the Transition to Adulthood Alliance on Twitter: @T2AAlliance

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies