Underemployment is inflicting huge pain on the British economy: we need to do more

In aggregate, workers would like to work about 20m more hours per week

A new paper I have written with David Bell of the University of Stirling tackles underemployment in the UK labour market. Workers want to work more hours, but there is insufficient demand to justify those additional hours. This phenomenon has been evident in the UK labour market for some time, but has grown significantly during the Great Recession.

Unlike the unemployment rate, which measures the excess supply of people in the labour market, the underemployment index measures the excess supply of hours in the economy. It combines the hours that the unemployed would work if they could find a job with the change in hours that those already in work would prefer. This index continued to increase during 2012, even though unemployment was stable.

The unemployment rate is the most used measure of slack in the labour market, showing how many people are actively seeking work and are without a job and generally reported as a proportion of the labour force – the employed plus the unemployed.

The UK unemployment rate rose from a low of 5.2 per cent at the end of 2007 to a high of 8.4 per cent at the end of 2011 before falling back to 7.8 per cent at the start of 2013. But during the Great Recession, we have also seen a steady increase in the number of the employed who want more work than they are currently doing – they are underemployed, likely in part due to falling real wages.

Hidden number

The underemployed are defined as those currently in work who would prefer to work longer hours. Their ability to supply hours at the current wage is constrained by the level of demand in the economy, because there simply isn’t enough work around. Some of these people are classified in the official statistics as part-timers who would prefer to be full-time, but the phenomenon also applies to full-timers, which is not reported in the published ONS statistics. There has been such a dramatic increase in underemployment that the unemployment rate is now a poorer indicator of the degree of slack in the labour market than previously.

The Labour Force Survey (LFS) asks all of those who are not looking for a different or additional job whether they would like to work longer hours at their current basic rate of pay if given the opportunity. By the third quarter of 2012, 11 per cent of workers expressed a desire to work longer hours, compared with an average of around 7 per cent in the pre-recession period. The share of employees willing to cut their hours and accept lower pay has been falling since 2003, though it declined more steeply at the beginning of the recession. It then fell again following a partial recovery during 2009 and early 2010. The net effect is that the numbers of employees wishing to increase their hours have exceeded the numbers wishing to decrease their hours since early 2011.

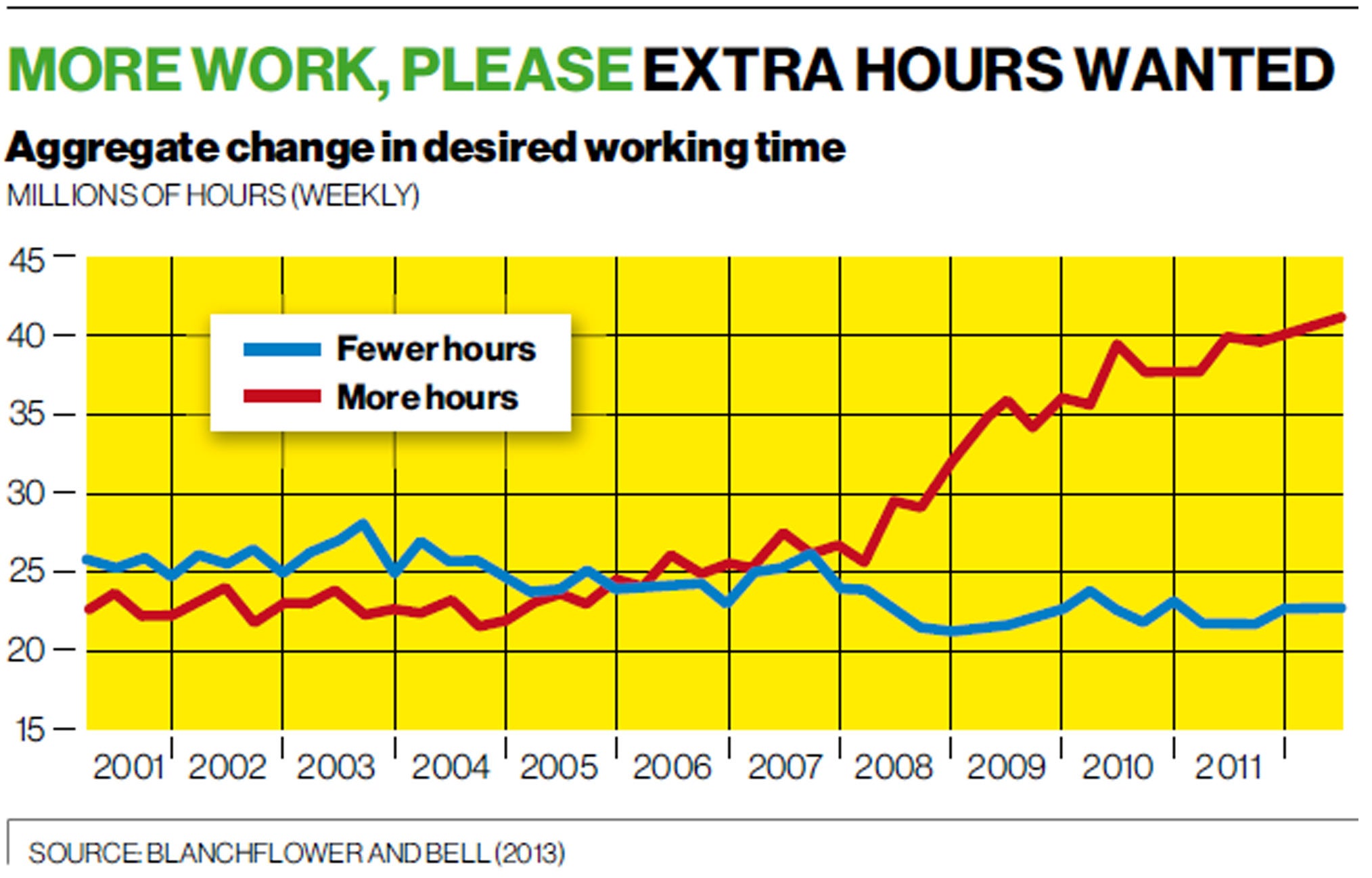

Both those wishing to work more hours and those wishing to work fewer hours are asked how many more or fewer hours they would like to work. Aggregate changes in desired weekly hours are given in the graph, which shows the sum of the additional weekly hours desired by those wanting to work more hours and the equivalent aggregate for those who want to work fewer hours. Until 2007, these aggregates are largely balanced.

Since the start of the recession in 2008, we’ve moved from a situation where in aggregate workers would like to work fewer hours to a situation where they would like to work about 20m more hours per week. That’s the gap between the two lines in the chart. Assuming full-year workers do 2000 hours, this is the equivalent of raising the number of unemployed by half a million. The underemployment rate is currently 10 per cent and worsening.

Not only do young people aged 16–24 have the highest unemployment rates of any age group, they also have the greatest gap between their unemployment rate and their underemployment index. In 2012, the supply of youth labour exceeded its equilibrium level by 30 per cent. Not only was the unemployment rate 21.6 per cent, but the shortfall in hours actually worked over desired hours increased the underemployment index by a further 8.4 per cent. In contrast, among older workers, the underemployment index is consistently lower than the unemployment rate.

Slack

This is because older workers typically wish to reduce, rather than increase, their hours, implying that actual hours exceed desired hours for this group and so the underemployment index is lower than the unemployment rate.

The major factor influencing the desire for extra hours has been the fall in real wages. Since the start of the recession in 2008, the Consumer Prices Index has risen by 17 per cent while average weekly earnings have risen by 7 per cent, suggesting real earnings have fallen by about one tenth during this period.

It does not appear, though, that this rise in underemployment has been because of a decline in average hours, which have actually risen since 2008. According to the ONS, average hours for full-time workers in January 2008 was 37.0 compared with 37.4 in December 2012. In the case of part-timers hours worked also increased, going from 15.5 to 15.8.

Perhaps the most important finding we have is that there appears to be significant slack in the economy. The primary argument made by the supporters of the Government’s current macroeconomic stance is that what’s going in the labour market shows that the UK economy is primarily supply not demand constrained, that the output gap – a widely used measure of spare capacity in the economy – is small, and crucially that we are now quite close to full employment.

Our paper potentially deals quite a big blow to that view by showing that there is very substantial spare capacity in the labour market; the implication being that if demand were higher, output could easily be higher, and it could be higher without exerting any significant upward pressure on real wages. So any further stimulus, whether fiscal or monetary, would not be inflationary. People want to work.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies