Christina Patterson: We don't want your apologies, or your remorse - unless they're from the heart

When I first touched a silicone implant, I felt sick. It felt squashy, but not in the way a breast feels squashy. It felt squashy in the way that something like, say, a waterbed, feels squashy.

It felt squashy, but it also felt hard.

When I looked at this thing, which looked, I thought, like a giant tear, and held it where I thought it ought to go, I thought that this was something I really didn't want in my chest. I thought that if I had to stuff it in a bra, so that it looked as though there was a breast where there wasn't going to be a breast, then maybe, though I hated the thought of it, I could. But I thought that if I had to know that this thing, which felt a bit like plastic and a bit like rubber, was next to my flesh, and under my skin, I'd feel sick all the time.

In the end, I was lucky. A very clever surgeon took a big chunk of flesh, and some of the blood vessels, from my stomach, and put them in the gap where my breast had been. When it healed, which took quite a while, what I had instead of a breast felt soft, like flesh, because it was. But when I heard that other women had had the breasts they'd lost replaced not just by giant tears, but by giant tears made from silicone that was meant to be used in mattresses, which are more likely to break than the ones that are meant to be put in people's chests, and more likely to inflame the flesh around, I felt very grateful, and very sad.

I thought that if I'd had cancer, and had the breast I'd lost replaced by something that was meant to be in a mattress, or even if I'd just decided to have implants because everyone around me thought that the most important thing for a woman was to have big breasts, and now was worrying that those implants would burst, I'd be very, very, very, very cross.

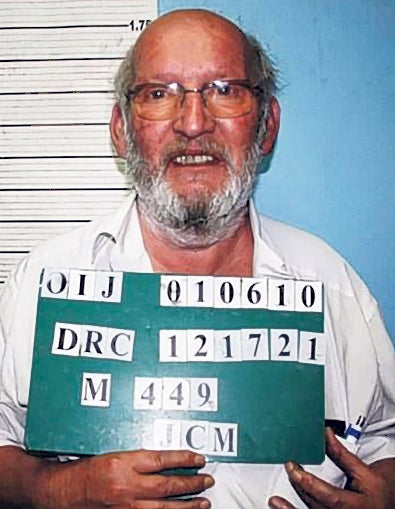

When I heard, for example, that the man who founded a company that supplied implants, which have been inserted into the flesh of about 400,000 women, knew that they hadn't been authorised for medical treatment, and had ordered employees to hide them when safety inspectors visited the factory, and had carried on doing this for 13 years, I think I wouldn't just feel cross. I think what I'd feel is that it might be a good idea to remove his testicles and replace them with something that might burst, and leak, and inflame the flesh around, and make him feel that a part of his body that was meant to give pleasure would give pain.

And when I heard that he'd said that he had "nothing" to say to the women who were having to have operations to remove the implants, and that he said that they were only filing complaints "to make money", I think I might feel that silicone testicles wouldn't be quite enough. I think I'd feel that it was bad enough for a man to make hundreds of thousands of women scared, and maybe ill, just to make more money, but to do that and not, apparently, give a monkey's about a single second of the anxiety he'd caused, was much, much, much, much worse.

But then I think I might also think that if you'd been doing something for 13 years that you knew was wrong, and which you'd tried to cover up, and you suddenly said you were sorry, it might be the kind of apology that didn't sound all that sincere. It might, for example, be the kind of apology that the President of Yemen gave this week when he said he was sorry for "any shortcoming" in his 33-year rule. It would be like the one Diane Abbott gave, after making comments that lots of people thought were racist, when she said she was sorry for "any offence caused". Or like the one Newt Gingrich gave when he was asked why he'd cheated on his wives and said that he "worked far too hard" and that things had "happened" that were "not appropriate". It would, in other words, be the kind of apology where you said you were sorry, but weren't.

This week, a man whose 10-year-old son was slaughtered on a stairwell said he wished the young men who killed him had been hanged. He was speaking as the older of his son's two killers left jail. Richard Taylor still dreams of the son he lost. He dreams, he says, that Damilola is "jumping all over" him. He wakes up, he says, and "he's gone". But he would, he says, have hugged his son's killers if they had shown "proper remorse". He would, he says, "have embraced them". It would, he says, have freed him to "move on".

But they didn't. They were children when they killed him, and could have learnt from the moment that changed their lives, and robbed a 10-year-old boy of his, but they didn't.

Nothing will take away the pain of what this father has lost. And the one thing that might have given him one tiny crumb of comfort hasn't happened, and probably won't. But Richard Taylor is right. He's right to say that remorse helps only when it's "proper". And that apologies mean something only when they're from the heart.

If Jean-Claude Mas, of Poly Implant Prothèse, had said sorry to the women whose lives he has turned upside down, his apology would have been worth as much as the toxic lumps of fake flesh he swapped for his soul.

Poverty? Just of the imagination

Some people might think he's already picked the long straw. They might think that sharing a bed with Carla Bruni was as jammy as it gets. But Nicolas Sarkozy would like, he has said, to "make a lot of money". He's impressed, he says, by Bill Clinton's lecture fees. "I would like," he says, "to fill my pockets, too."

When you're a president, there's almost nothing you can't see. There's almost nowhere you can't go. There's almost nothing you can't do. It's possible, I suppose, that you could meet some of the most interesting people in the world and decide that what interested you more than any of them, or than any of the things you'd seen or learnt about, was counting piles of cash. Possible, but very, very, very, very strange.

Why we all need divorce decorum

Breaking up, Neil Sedaka once wrote, is hard to do. But he was wrong. Breaking up is easy. What's hard, as so many "celebs" remind us, is to do it with good grace. No wonder Debrett's, which has tried to guide us in "correct form" for the past 50 years, has published a "guide to civilised separation". You shouldn't, it says, hack your ex partner's clothes to pieces. You should, it says, take a "minder" to events where they'll be, to monitor your "alcohol intake and emotions". You should, in other words, get a grip. Or perhaps you should just listen to Seal, who has just announced the end of his marriage to Heidi Klum, but described her on TV this week as "the most wonderful woman in the world".

c.patterson@independent.co.uk // twitter.com/queenchristina_

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies