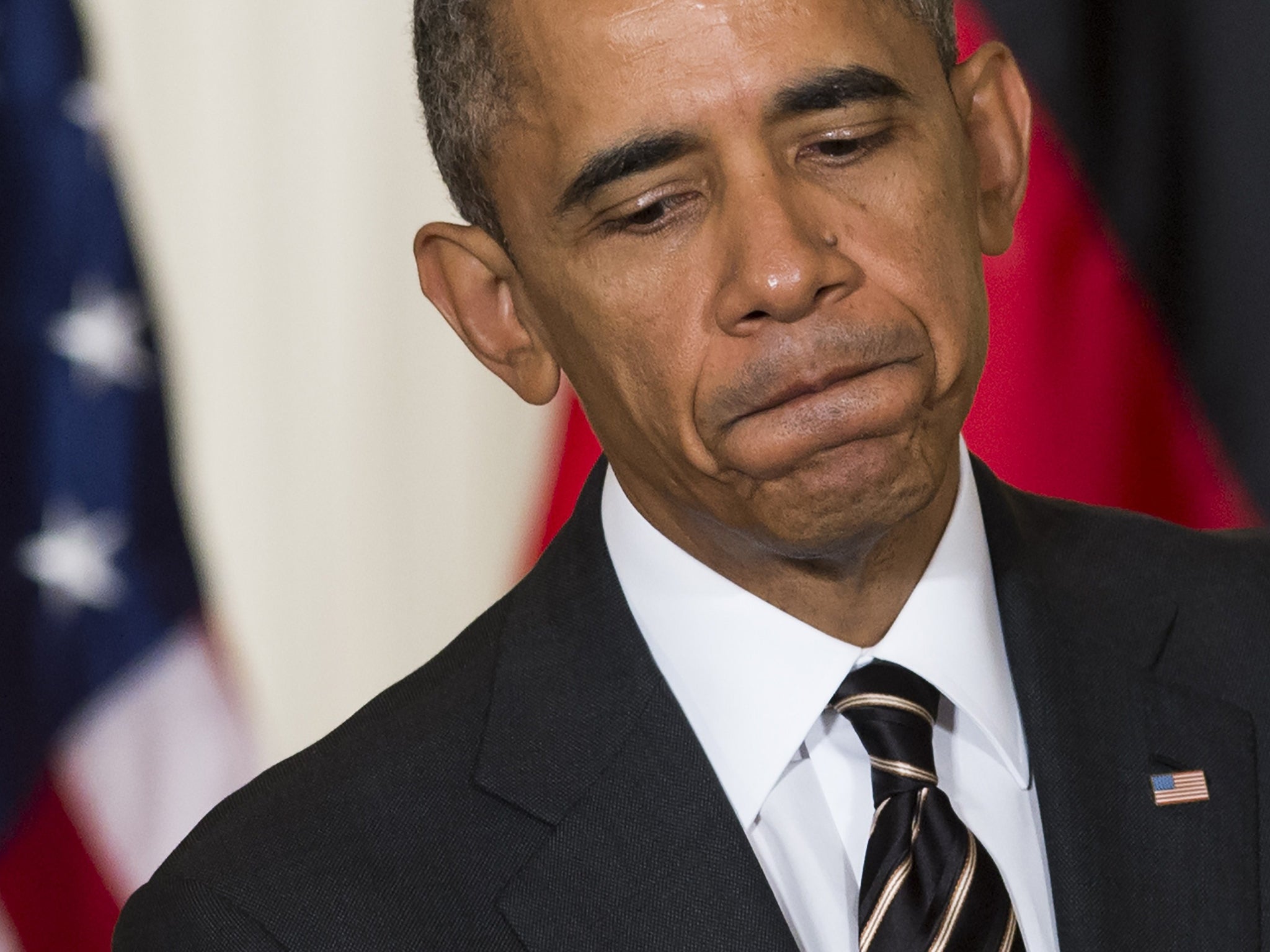

War or peace, Obama just can't win

No one wants another Iraq, but that doesn’t stop the President being criticised on all sides for caution on the world stage

Damned if you do, and damned if you don’t.

George W Bush was blamed, rightly, for launching his war of choice in Iraq. Now, his successor Barack Obama is assailed from every side for doing nothing as the world – from Syria and Libya to Islamic State, Boko Haram and radical Islam, to the crisis over Ukraine – seems to be going to hell in a handbasket.

An enduring fallacy has it that foreign policy doesn’t much matter in US elections, that they’re invariably about bread-and-butter domestic issues, and which candidate Joe Public would rather have a beer with. In truth, Obama’s opposition from the outset to the Iraq invasion was a key factor in his defeat of Hillary Clinton in the primaries and then John McCain in 2008.

And foreign policy shapes presidential legacies: Lyndon Johnson and Vietnam; Jimmy Carter and the Camp David accords and the Iranian hostage crisis; Reagan and victory in the Cold War. Bush senior is remembered for the first Iraq war, his son for the second. But Obama thus far? The killing of Osama bin Laden, the expanded use of drones – and that’s about it.

For the rest, his critics say, just vacuity. He dithers, he has no personal touch, he’s naïve, he over-analyses, he leads from behind, he makes promises and threats he doesn’t keep. And when it comes to Obama’s famous “red line” over Bashar Assad’s use of chemical weapons, they have a point.

The complaints are not just from neo-cons, or right-wingers who call into question his patriotism, and even (still!) his citizenship. “I do not believe the president loves America,” Rudy Giuliani, a former mayor of New York and Republican presidential candidate said last week. Democrats too are unhappy: “Great nations need organising principles, and ‘Don’t do stupid stuff’ is not an organising principle,” Hillary Clinton has said, attacking Obama for his risk-aversion. The left, meanwhile, is dismayed at America’s lack of concrete support for the 2011 Arab Spring, and what it sees as a sell-out on human rights in places such as Egypt.

To which Obama’s reply is, get real. The United States can’t solve all the world’s ills. “You take the victories where you can,” he told the online network Vox in a revealing interview last month, “You make things a little bit better rather than a little bit worse.” He said this didn’t mean that “America is withdrawing or there’s not much we can do. It’s just a realistic assessment of how the world works.”

This cuts against the national grain. In baseball parlance, Obama’s goal is to score singles and doubles. But in foreign affairs, Americans yearn for home runs: clear victories and quickly imposed solutions. A White House national security paper advocates “strategic patience”. Patience is not America’s best known attribute. Now, though, America’s allies are showing impatience too. As a result, Obama must navigate between Scylla and Charybdis.

On the one hand, the US is the nearest thing going to a global policeman, the lone superpower to whom the world looks when some international crisis flares up. On the other, it seems to be abdicating that role. But no democratically elected leader can ignore public opinion, and in part, Obama’s difficulties stem from a national schizophrenia over foreign policy. Americans want a bit of swagger, proof that the US is top nation. But after George W Bush’s disastrous war in Iraq – whose claim to be the country’s greatest foreign blunder in half a century (Vietnam included) grows with each passing month – the last thing they want is a repeat.

Reasonably enough, Obama has concluded that when an immediate and vital US interest is not at stake, broad international coalitions are the way to go. But this principle is muddied by another reality: despite horrific images of beheadings and immolations that flash around the globe in seconds, today’s world is actually growing less violent. Old-fashioned inter-state wars are in decline, replaced by messy internal conflicts that often spill across borders. Hence the paradox of a world with fewer wars, but less peace. The question when to intervene becomes ever more complicated.

In these circumstances, “strategic patience” makes sense. But that doctrine comes up against an eternal truth of all human relations: that power lies in the perception of power, and the perceived readiness to use it. Too easily, caution is perceived as weakness. Vladimir Putin’s behaviour over Ukraine suggests he falls into this camp. So too may Iran as talks continue for a deal on Tehran’s nuclear programme, whose success or failure, and all that flows therefrom, may prove Obama’s most important foreign legacy.

The hawks bay for blood: address Putin with force, the only language Russia understands, they clamour, and make clear to Iran that if it doesn’t stop enriching uranium, its nuclear facilities will be bombed to smithereens. But who wants a new war – whether one against Iran whose long-term scale would probably dwarf Iraq in 2003, or, heaven forfend, against Russia.

Obama is right. The US can’t do it all. That is simply a recognition of reality. But no previous president could have uttered such opinions – until this son of a Kenyan, who spent part of his childhood in Indonesia, who understands that other countries have other points of view, that every country, not just the US, regards itself as “exceptional” in its way. And which previous president, at a National Prayer Breakfast, held amid revulsion at the barbarities of IS, would have pointed out that Christianity had such sins as the Crusades and segregation in its own past.

More pertinently, neither Clinton nor the Republican contenders offer alternatives: not Jeb Bush’s vaguely hawkish platitudes last week in a “major foreign policy speech” which could not escape the shadow of his brother’s Iraq debacle; and certainly not Chris Christie’s boast that if he’d been in the White House, Putin would have backed down over Ukraine. Dream on.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies