The allegations against Philip Green are sickening – but naming him in parliament points to problems in the system

It is said that two individuals who signed NDAs with Green’s companies did not wish for the injunction to be removed

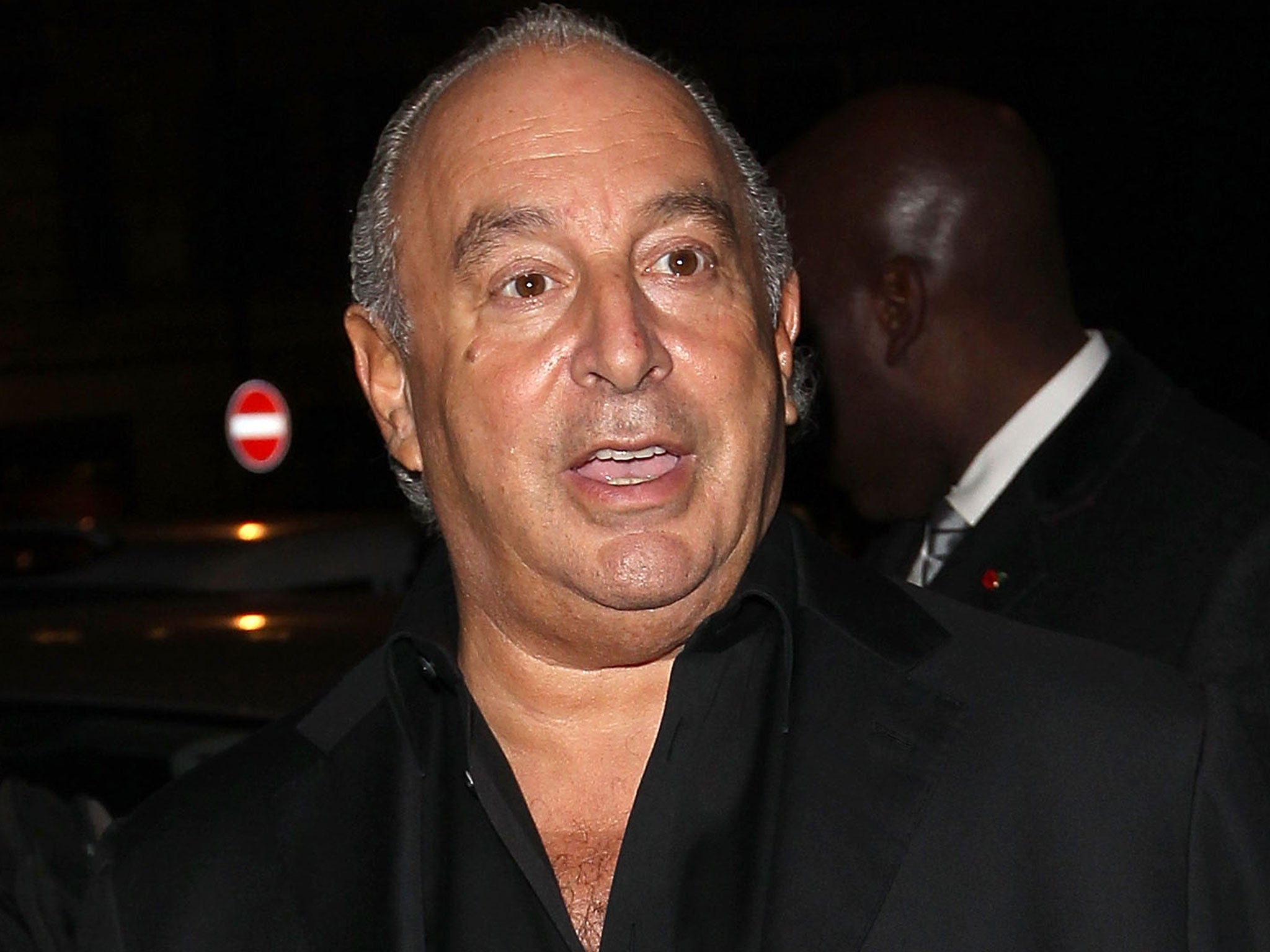

Sir Philip Green, it is fair to say, is unlikely to attain the status of national treasure anytime soon. Some find him brash. He owns a large yacht. His lifestyle is ostentatious. He is robust in defending his interests. None of these are crimes. His business exploits alone have been controversial, to say the least, and now he has been named in the House of Lords as the senior executive who had an injunction placed to prevent reporting of allegations of sexual harassment and racial abuse. Sir Philip “categorically and wholly denies” allegations of “unlawful sexual or racist behaviour”.

Peter Hain, a former Labour cabinet minister hitherto not one of Sir Philip’s high profile critics, used the ancient right of parliamentary privilege to remove Sir Philip’s anonymity. Should he have done so? There is a strong case, in this instance, that he should not, despite the obvious public interest – acknowledged in a lower court – in the story.

The point about an independent judiciary is that it is just that. Parliamentary privilege should be untrammelled – but, to preserve its sanctity, it should also not be abused. Lord Hain has seen fit to, in effect, second-guess the judgment of the courts, without the benefit of legal expertise or the full evidence being placed before him. It is, in other words, not his job to lift an injunction. His action was entirely lawful. It can be justified on all manner of grounds. It is constitutional; given the unlimited freedom membership of the Lords of the House of Commons confers on politicians. But the privilege has been used carelessly, in a quasi-judicial fashion. Lord Hain also needs to offer a fuller explanation of his links to the firm of lawyers advising the newspaper that first levelled the accusations against Green.

Moreover, the injunction was temporary. A full hearing would have been heard early next year in any case. So far as can be seen, there was no huge urgency in having the injunction lifted immediately. It could – should – have waited for the courts to decide whether to do so. The legal processes may be frustratingly slow, for all sorts of reasons good and bad, but they are what they are. If impatience with the judicial system was justification enough for members of parliament to, literally, prejudice proceedings we would be in a difficult place indeed. The injunction might well have been lifted next spring, in any case.

And what, in a hypothetical way, if an MP decided to lift an injunction on proceedings in which the principal is, to use the term loosely, “innocent”? What if their anonymity has been removed without any proof that they have done anything wrong? That is why parliamentary privilege is used so seldom. It is a currency that is easily debased.

The calls have gone up for Sir Philip to lose his knighthood. Certainly the accusations made against him are – if true – horrifying, unacceptable and wholly incompatible with normal and decent citizenship, never mind such a high honour. Yet he has been convicted of no criminal offence. It is also said that two of the individuals who signed NDAs with Sir Philip’s companies did not wish the injunction to be removed. All five individuals were free to make “legitimate disclosures” (including reporting criminal offences) if they wished to do so.

Whatever the facts of this case, there is a wider question about the use and misuse of NDAs, which ministers are presently examining. There is also a case – it would need to be tested properly – that NDAs are, in a practice, unenforceable because they conflict with the Human Rights Act, especially the right to free speech. Because of the cost and hassle of going to law many employers simply cannot be bothered to enforce them in any case. But still, in some cases they can be imposed on individuals who are in a vulnerable position, and agreed to even with access to legal advice. In general, NDAs should not be used to wish away or cover up criminal behaviour. And they should never be the tool of the bully.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies