The Irish border issue presents a significant obstacle to Brexit

The finest diplomatic, political and economic minds in Europe have not been able to solve the insoluble – how Northern Ireland can be outside the EU’s single market and customs union, but have no economic border with Ireland

Theresa May has spent the last year or so learning how to put a brave face on the most calamitous events in recent British political history – some her fault, some not.

Today, in the convivial company of European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker, the brave face was on display once again, the Prime Minster sounding as upbeat as she could be about the failure – there is no other word for it – of the latest round of talks. In this she was abetted by the silken rhetoric of Mr Juncker, something of a charmer over the lunch table by all accounts, but, if anything, Mr Juncker only made matters worse when he let slip that there were “two or three” issues still open for further negotiation and “consultation” – which is one or two more than might have been assumed. In other words the latest iteration of the historic “Irish question” is not the only sticking point, as appeared from some of the more positive mood music emanating from Brussels and London in recent days.

Some of this, in fairness, is not Ms May’s fault, and not simply because she was once, in a lost world far away, a Remainer, albeit a highly reluctant one during the EU referendum. It is simply that, after around 18 months of wrangling, the finest diplomatic, political and economic minds in Europe have not been able to solve the insoluble – how Northern Ireland can be outside the EU’s single market and customs union, but have no economic border with the Republic of Ireland.

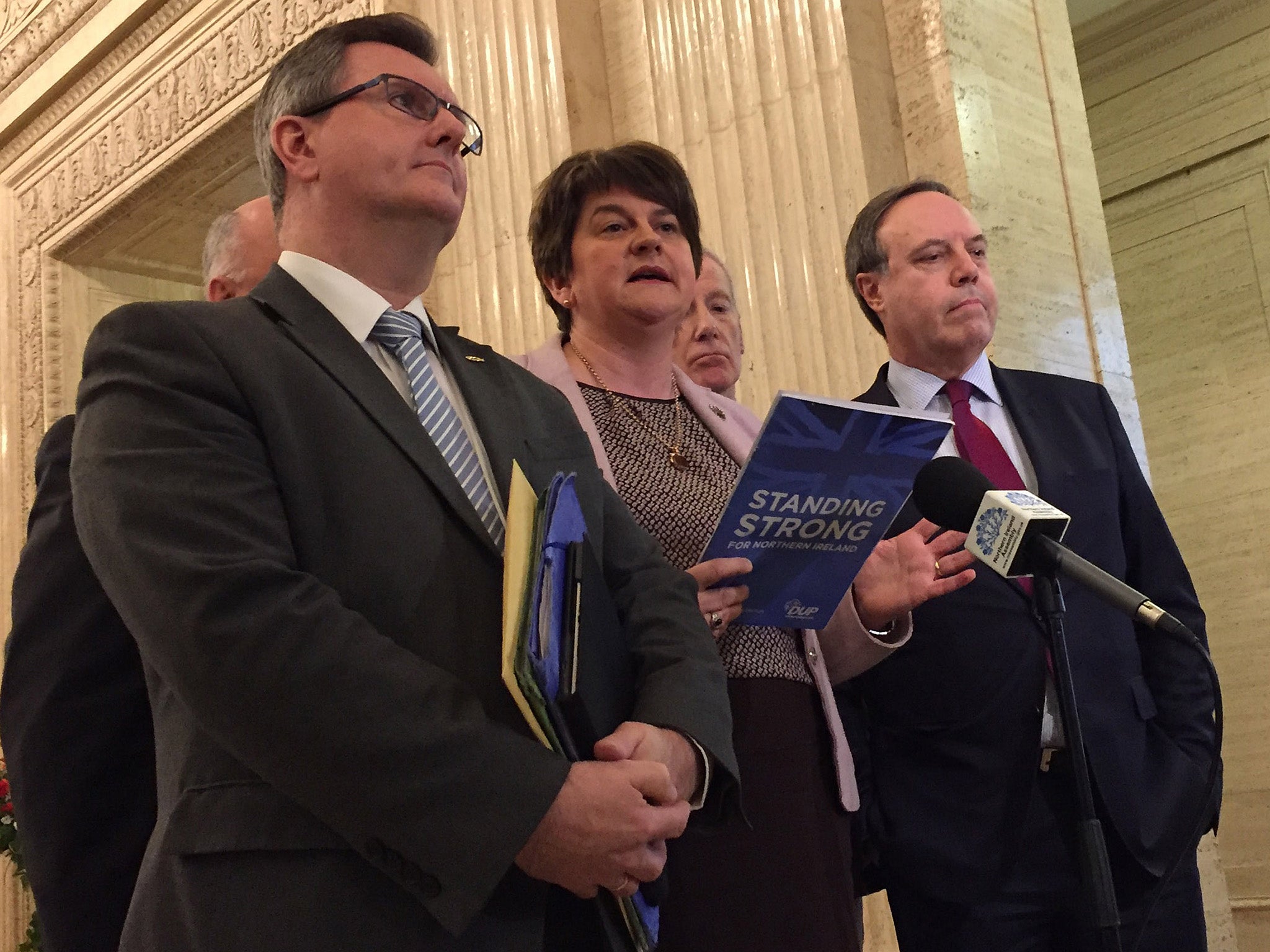

In a thoughtful and creative position paper in the summer the British Government attempted to solve the problem by suggesting that new technologies could be used to remove most of the difficulties. Former Taoiseach Bertie Ahern suggested a blind eye could be turned to small-scale movements of goods and people strictly outside of the letter of Brexit. The Irish government suggested, successively, an economic border between Great Britain and Northern Ireland (and thus the EU). A new wheeze, of “regulatory convergence” between Ireland and the EU on the one side, and Northern Ireland on the other, was swiftly agreed by the British Government, and just as rapidly spat out by Arlene Foster, leader of the Democratic Unionists.

So this failure to settle the economic status of Northern Ireland by giving it special treatment suggests that the problem is so intractable as to represent a significant obstacle to Brexit in its own right – along with still unresolved issues about the rights of EU citizens in the UK and the divorce bill. To put it colloquially, the British people may soon wonder whether the as yet undefined and uncertain benefits of Brexit – many of which have evaporated on the journey from the side of the Brexit bus to reality – are worth all of the hassle. At the very least they would be forgiven for asking for another referendum vote on how things seem to be shaping up for a deal.

Theresa May cannot be blamed for failing to make two plus two make five, and neither can anybody else. There is genuine goodwill about the problem, and about the determination to keep the UK-Ireland common travel area that has lasted since partition in 1922 (and of course for centuries before), and avoid hard borders. If goodwill and a sense of partnership was sufficient to solve the Irish border question it would have been sorted long ago. That it has not is extremely ominous, ether for peace in the province or for the prospects for a meaningful Brexit.

Where Ms May plainly didn’t do her homework was in squaring the political party she relies on for her survival at Westminster – the Democratic Unionists. It seems as though Ms May might have been under the misconception that the Unionists could be “bounced” into going along with “special status” for Northern Ireland. The Prime Minister, in a very tight corner and desperate to move to the next stage of trade talks, might have risked the support of the DUP to seal this first phase of the Brexit deal. The cynical calculation usually is that the DUP would be unwilling to overthrow Ms May if it meant the arrival of the IRA-sympathising (in their view) Jeremy Corbyn into No 10.

If so she made a fundamental mistake. First, Ms May has underestimated the confidence and belligerence of the DUP, whose constituency could never accept different economic arrangements in Ulster to those in the rest of the UK, for political and for financial reasons. Moreover, there principle is that Northern Ireland leaves the EU on the same terms as the rest of the UK – and terms themselves appear secondary. Thus, if Jeremy Corbyn wants a soft Brexit where the whole of the UK stays in the single market and some version of the custom union, then that would be a more “unionist” policy than that of Ms May, who is proposing to erect a border between Northern Ireland and the UK, with customs checks on the ferries and at the airports.

This is not what Ms Foster and her friends came into politics to deliver. In their 2017 election manifesto the DUP stated they wished to see a “comprehensive free trade and customs agreement with the European Union; ease of trade with the Irish Republic and throughout the European Union”; “particular circumstances of Northern Ireland with a land border with the EU fully reflected”; and “frictionless border with the Irish Republic assisting those working or travelling in the other jurisdiction”. Mr Corbyn’s policies are presently closer to those commitments than are Ms May’s – which might mean Northern Irish citizens having to present a passport to enter the rest of their own country.

Brexit, then, is throwing up some strange and unexpected contortions in the British body politic. At the moment, those contortions make the medium-term survival of the Prime Minister even less likely than a few weeks ago.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies