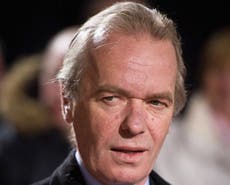

Martin Amis: The writer’s rant about Jeremy Corbyn’s lack of exam success says more about the biter than the bit

No doubt to a man who achieved a 'congratulatory' first at Oxford and published his first novel at the age of 23, two A-levels and retirement from the educational process at the age of 18 is a bit of a come-down

Long relished by the media, and long disparaged by people who imagine that a writer’s reputation ought to depend on the books he, or she, writes, the Martin Amis row comes round as regularly as a migrating swallow. What generally happens is this. From the comfort of his exile’s brownstone in Manhattan, Mart files a searing couple of thousand words on some vexed and unfathomable topic for a British newspaper – the rise of the militant pensioner, say, or, as happened last week, the intellectual nullity of Jeremy Corbyn, whereupon all hell erupts. The proud author murmurs that he can’t understand what all the fuss is about and discreetly retires, only for another spat, strikingly similar in tone, to break out six months or a year later.

It is all very cunningly done and, in the case of poor Mr Corbyn, an absolutely vintage Mart performance, in which the Labour leader, were he to have read The Sunday Times, would have found himself sneered at for being under-educated, full of second-hand ideas, inflexible, dull-witted and – an accusation which has wrecked many a promising career – “humourless”. Further targets for Amis’s asperity included his vegetarianism and his teetotalism. Mr Corbyn is also, apparently, stupid, smug and out of touch with the English people. For their own part, one or two of Mr Amis’s critics – I can’t imagine why – have attributed this titanic disdain to snobbishness.

No doubt to a man who achieved a “congratulatory” first at Oxford and published his first novel at the age of 23, two A-levels and retirement from the educational process at the age of 18 is a bit of a come-down. At the same time, the Mart-attack sets loose so many hares across the greensward of our national life that it is difficult to disentangle them. But the two most obvious – there is a third, which I shall get to later – are these: if Mr Corbyn is under-educated, then what does it mean to be “educated” in the early 21st century? And, having established what an educated man or woman is, should we expect our politicians to aspire to this exalted state? What is in it for them and, perhaps more important, what is in it for us?

To return to first principles, most onlookers would probably concede that the modern view of being “educated”, whatever it is, represents a substantial falling-off from the standards of the later 19th century. There is, for example, a celebrated passage in Jude the Obscure, in which Jude Fawley – a self-taught stonemason keen on taking holy orders – reckons up the amount of knowledge he has managed to accumulate. The list includes two books of The Iliad, Hesiod, Thucydides, the Greek Testament, three books of Euclid, information about the early Church Fathers “and something of Roman and English history”. A subsequent daydream about “Livy, Tacitus, Herodotus, Aeschylus, Sophocles, Aristophanes…” is only cut short by the arrival of the woman who will start blighting so many of his hopes.

And, by the measure of the late-Victorian age, Jude is scarcely “educated” at all. The novelist George Gissing (1857-1903), who quitted formal education at the same age as Mr Corbyn, was a terrifying polymath who spent his leisure reading the classics and philosophy, and embarked on feats of reading that would leave his modern-day equivalents ashamed by their lack of intellectual frills. Am I, with my 10 O-levels, three A-levels and Oxford degree in modern history, what you might call “educated”? By George Gissing and Jude Fawley’s yardstick, not in the least. Working knowledge of British and American history, ditto politics, smattering of geography, a grasp of English Literature that might be compared to Sam Weller’s knowledge of London (which Dickens describes as “extensive” but also “peculiar”), an ability to just about hold a conversation in pidgin French if the vis-à-vis speaks very slowly, but beyond that, well, nothing. It is a shameful fact, but unquestionably true, that the only equation I can remember from a year’s physics is that density equals mass over volume.

As to what that formula means, in practical terms, I neither knew nor ever wanted to know. All of which, I suspect, on the Amisian scale of values, makes me just as much of a dullard and hapless second-rater as poor Mr Corbyn. Much better, no doubt, to define “educated” in the stark, practical sense of having been through what the modern age regards as an education, that is spent two years in a school sixth form or further education college and acquired a decent (i.e. upper second-class) degree at a university. But even if we accept that this is what being “educated” means, is it necessarily something that our politicians have to acquire before we start taking them seriously?

This question looms all the more largely when you examine all those bygone cadres of politicians who prided themselves on their intellectual éclat. Harold Wilson’s first cabinet, it may be remembered, contained the bearers of nine first-class Oxford degrees – just like Mr Amis – and what, you might reasonably inquire, were the achievements of that happy band over the next six years? Ernest Bevin, who went out to work at 11, was one of the finest foreign secretaries the country ever had. All of which is to ignore the deeply instructive story of James Callaghan, Wilson’s successor, on which I once, quite by chance, managed to eavesdrop myself.

This happened in the autumn of 1977, when I found myself invited to join a line-up of teenagers greeting the then prime minister as he inspected Norwich Cathedral. “Well then,” Jim inquired avuncularly as he drew near, “what are you going to do?” I replied “I’m thinking of going to Oxford, Prime Minister.” And, suddenly, for perhaps a second or two, Callaghan looked ill-at-ease. There was a silence, after which he diffidently proposed that “There are other places, you know.” The sheer oddity of this exchange went unexplained until I came across Susan Crosland’s biography of her husband Tony, Callaghan’s first foreign secretary, which discloses the considerable chip that Callaghan bore on his shoulder about having left school at 17.

Ernest Bevin, who went out to work at 11, was one of the finest foreign secretaries the country ever had

Tony Crosland also contains an episode in which Callaghan demands of his cabinet colleagues “I hear you all think I wouldn’t have got a second if I’d been to Oxford”. Not at all, Crosland – not unpatronisingly – assures him. He could have got a first had he allowed himself more time to reflect. Callaghan’s first words, on entering 10 Downing Street in 1976, are supposed to have been a variant on “all this and I never went to university”. The student of Callaghan’s decade-and-a-half at the top of the political tree, in which he brought off the unique feat of holding all four major offices of state, might think he did OK despite this dreadful handicap.

But back to the third hare that Mart set loose in his Sunday Times harangue. This is his not-quite-unspoken assumption that the condition of being “educated” can be detached from the bedrock sharpness or instinct that millions of people who have never been near Tate Modern or the Man Booker Prize dinner naturally possess, that it consists merely of the training necessary to crack one or two cultural codes not available to hoi polloi. All this tends to suggest that being “educated” has very little to do with “education”, in much the same way that being “cultivated” has nothing to do with culture and is merely the excuse for a lot of nonsense about first nights, RA exhibitions and the pas de seul being divine.

A fine distinction, perhaps, but Mr Amis, of all people, ought to be capable of making it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies