The Only Way is Ethics: What’s in a name? That depends on the accusation

Surely we should be allowed to know when the police are arresting people

Three years ago there was a striking change to the British criminal justice system, when teachers accused of an offence against a pupil were granted anonymity until such time as charges were brought.

It had long been said that teachers are particularly vulnerable to false – even malicious – allegations by students. And it is certainly true that teachers’ careers, and reputations, have been tarnished beyond repair by unsubstantiated claims being aired publicly.

Yet it always seemed to me a dangerous precedent to set. If teachers could have a legal right to anonymity, why not other people? There has, in particular, been a long-running question about whether individuals accused of rape or sexual assault ought to be granted the same protection. Again, the basis for suggesting they should is the degree to which public knowledge of such allegations affects the accused, even if they are not brought to trial (let alone found not guilty).

On the other side of the argument are those who point out that publicity often encourages other victims to come forward. In the case of anonymity for teachers, there is the specific absurdity that even if allegations are true – and for instance the teacher is sacked – they cannot be discussed, by the media or anyone else, unless a charge has followed.

This plays to the most compelling argument against anonymity for people accused of crime, which is simply that transparency is vital to a well-functioning criminal justice system. Unless it is necessary to withhold it, surely we should be allowed to know, for example, when the police are arresting people.

With all this in mind, I was surprised to find myself on the fence last week in relation to a report about a woman who had killed herself after the acquittal of a man alleged to have raped her. The woman’s mother had spoken of her daughter’s despair at the verdict; her suicide clearly raised important questions about the way witnesses are treated in the court process, especially in cases involving sexual attacks.

But should we have named the acquitted man? There was no legal or regulatory reason not to; and the outcome of the trial was made clear. Yet in light of the not guilty verdict, was it right to implicate him in the death of his accuser? I felt uneasy about it, but in the end we – like most outlets – included the name. And in the name of transparency, perhaps on balance that was the right call.

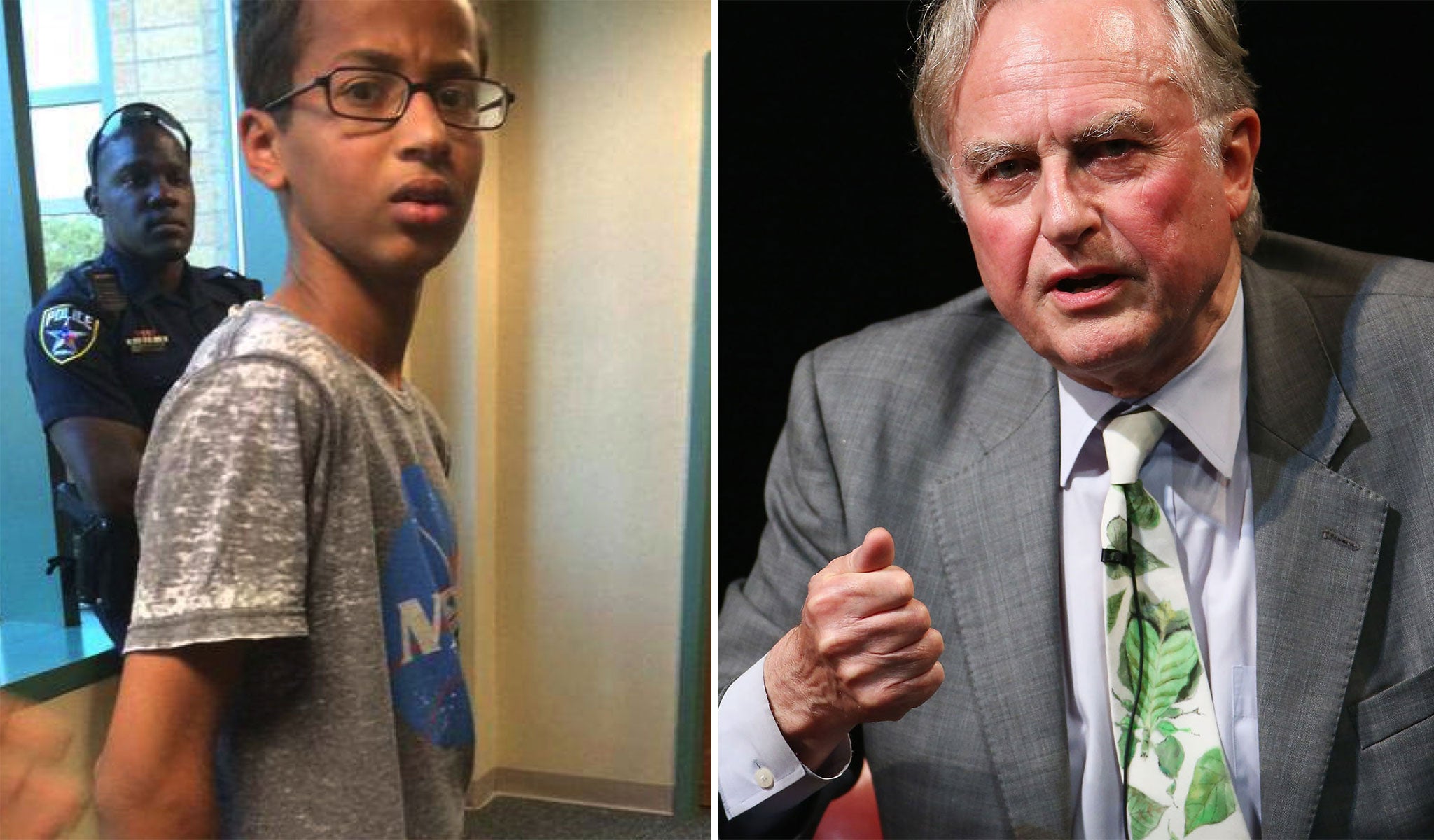

Dawkins and the sleep of reason

Richard Dawkins caused a kerfuffle last Tuesday when criticising the American boy who came to public attention after being arrested for bringing what teachers believed was a bomb to school. In fact, it was a clock. Depressingly, the boy and his family are now suing for $15m (£9.9m) over the incident.

In challenging those who defended the boy on account of his age, Dawkins suggested that he was old enough to take responsibility for the decision to sue – and then tweeted a link to a child carrying out an execution for Isis. The implication seemed to be that neither boy could be absolved by reference to their youth.

Regrettably, when embedding Dawkins’ tweets in our web report, the image to which he had linked – of a boy holding a knife to the throat of a prisoner – was visible on our site. Among the many perils of Twitter, this was a new one: we re-embedded the tweet in a different format post-haste.

As for Dawkins, if the core feature of atheism is (supposedly) reason, then he is becoming a bad advert for it.

Will Gore is Deputy Managing Editor of The Independent, i, Independent on Sunday and the Evening Standard

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies