Last week’s most heartening arts world story could be found in some remarks dropped by Frances Bean Cobain, daughter of the late Kurt and his wife Courtney Love, in the course of an interview designed to promote the forthcoming biopic of her father, Cobain: Montage of Heck. “I don’t really like Nirvana that much,” the 22-year-old Ms Cobain declared, of Kurt’s trail-blazing early Nineties trio. “Sorry, promotional people.”

Claiming that her musical taste extended to Mercury Rev and Oasis (“the grunge scene is not what I’m interested in”) she was also determined to peel any last shred of camouflage from the roof of her parents’ marriage – “I always knew their relationship was toxic” – while characterising herself as a “fix-it baby”, conceived to paper over the cracks in a union eventually brought to a close by her father’s suicide.

The satisfactions to be got out of this bleak analysis of Kurt’s music, his marriage, the myths that surround him 20 years after his death and even the reasons for her own existence lie, on the one hand, in its realism – a quality absent from most relationships at the best of times – and, on the other, in the blow Ms Cobain appeared to be striking for that very common piece of human jetsam, ceaselessly blown about on the contemporary tide, the artistic titan’s child.

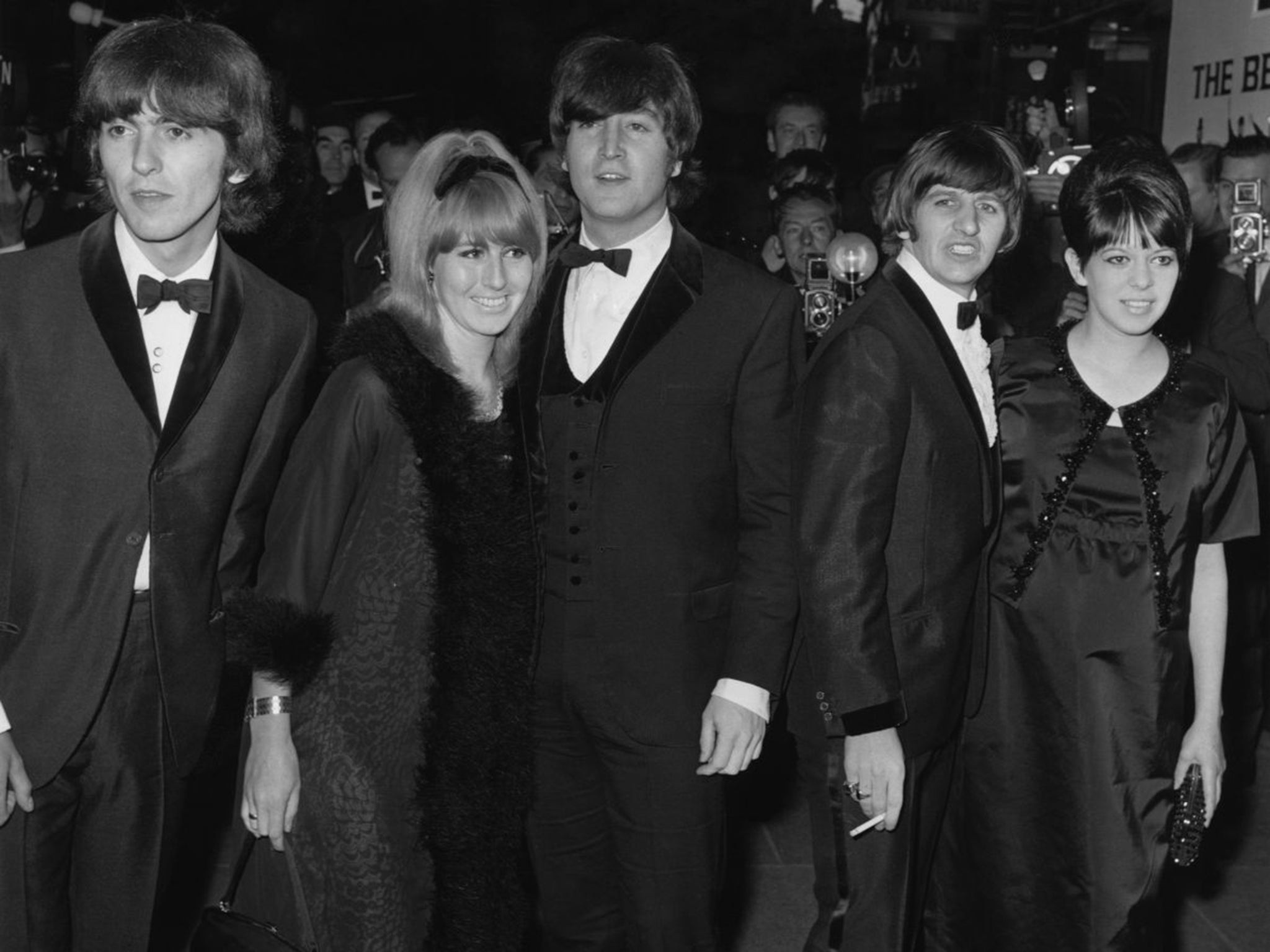

If the recent death of John Lennon’s first wife Cynthia reminded us what a truly awful destiny it very often is to be married to a famous novelist, a Hollywood A-lister or a globe-bestriding rock star, then Frances Bean’s comments about her dad moved the dilemma down a generation by suggesting that the next worst destiny is to be one of their children.

Grim as some of these inheritances undoubtedly are, the parameters of this debate are not entirely the same. Naturally, there have been plenty of creative behemoths whom posterity has convicted of mistreating or neglecting their children. Dickens, for example, seems to have simply squeezed the life out of his progeny, gave them the names of his favourite writers (one unfortunate was christened Edward Bulwer Lytton Dickens) built them up in his imaginations as models of rectitude and talent, and then cast them aside once they failed to shape up. Of his 10 immediate descendants, only two, Charley (a literary journalist) and Henry (a barrister), were in any way successful in the careers they pursued. Others were sent to sea or despatched to Australia to work as sheep-farmers in what can only be construed as parental exercises in damage limitation.

Yet this was only part of the problem confronting the wistful, bewildered and at times downright sullen faces that stare out of Dickens family portraits and individual miniatures. Even worse, perhaps, were the trails of well-nigh mythological glory that hung about the ghost of dear papa in the decades after his death when he was elevated to a select national pantheon that included Chaucer, Shakespeare and Milton.

How, to put the matter bluntly, is it possible get on with living life on your own terms if every library you venture into owns a complete set of your father’s works and the smile that crosses the features of 90 per cent of the people introduced to you is entirely vicarious, based on your paternity rather than your own particular attractions?

Naturally, the tocsin of parental celebrity clangs just as loudly in the modern age as it did in the era of Bleak House and Little Dorrit. A literary friend of mine once told me of the holiday she had spent in the south of France with the daughter of highly regarded modern novelist X. The two of them were to share a room. On inspecting the bookcase they discovered a dozen or so productions of X’s pen, whereupon his daughter, saying nothing, but with a single dramatic sweep of her hand, up-ended the shelf on to the floor. Thinking about this horribly symbolic gesture, and knowing something of the background, I don’t believe that it was a result of X’s daughter disliking her father, or – less culpably – disliking his books, or even being jealous of his achievements. Rather, it was a silent plea for autonomy, an urgent desire not to be followed on holiday by constant reminders of the brooding presence of the man who made you who you were.

Inevitably, relationships of this kind are set in even starker light when the sons and daughters of celebrated creative types nurture (as Ms Cobain apparently does) artistic aspirations of their own, for the odds of picking up the torch that your father or mother set ablaze are not high. Genes seldom transfer with quite the same lustre, or, if they do, rarely have a habit of manifesting themselves in quite the same area of artistic achievement: the Edwardian artist George Lambert, for example, begetting a musician (Constant) and a sculptor (Maurice) with the former himself siring the louche, rock band-managing Kit; or Thackeray’s line of descent taking in his daughter Annie (a proficient novelist if not quite in the same league as her dad) and finally working itself out, several generations later, in the appearance of the pub landlord and Nigel Farage-confounder Al Murray.

Given these impediments, the emergence of a father-son or mother-daughter team operating at more or less the same creative level is highly unusual. Back in the mid-1980s, noting the simultaneous appearance of one of his own novels and one of his son Martin’s, Kingsley Amis congratulated both parties on what he imagined was a unique achievement. And yet even the Amis father-and-son alliance was prone to periodic fracture and remonstration. “Did I tell you Martin is spending a year abroad as a TAX EXILE?” Amis père wrote to Philip Larkin in May 1979. “Last year he earned £38,000. Little shit. 29, he is. Little shit.” There were other complaints about Amis junior’s novels, many of which his father claimed to find unreadable.

That New Statesman’s weekend competition for implausibly titled books, won by the entrant who suggested Martin Amis’s “My Struggle”, has since gone into literary history, but it ignores the very genuine difficulties that Amis junior experienced at the start of his career that had nothing do with his own talent but were simply based on perceptions of his father.

Some aspirants find the whole business of working in the family business too unnerving and go off at a tangent – Auberon Waugh, for example, who after a handful of novels gave up any attempt to emulate his father Evelyn and settled for being a highly distinguished journalist.

All of which brings us back to Frances Bean Cobain, who not only has to spend the next month reading accounts of her parents’ ropey marriage and her father’s suicide, not to mention endless paeans to a brand of music she doesn’t appreciate, but will presumably spend the next few decades attempting to forge a life for herself in the ever more romanticised shadow of the man who wrote “Smells Like Teen Spirit”. It is all reminiscent of the career of Vyvyan Holland (1886-1967), the younger son of Oscar Wilde, who as his friend Alec Waugh once delicately put it “detested notoriety as much as his father had delighted in it”.

In the end Holland managed to confront and defy these demons by writing a spirited autobiography, Son of Oscar Wilde. With any luck, in the fullness of time, Ms Cobain will do the same.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies