A split or a unifying leader are the only ways to end Labour's civil war

A Labour MP could grow into a Wilson-like figure and seek to be a unifying leader…Only political titans willing to age quickly need apply for that task

Given the crisis engulfing the Labour Party, a visitor from Mars might assume that its divisions over Syria and other policies were freakishly unusual. They are not. The Labour Party has always suffered from deep divisions even during rare phases when it appeared to be formidably united. The difference now is that the divisions take a unique form.

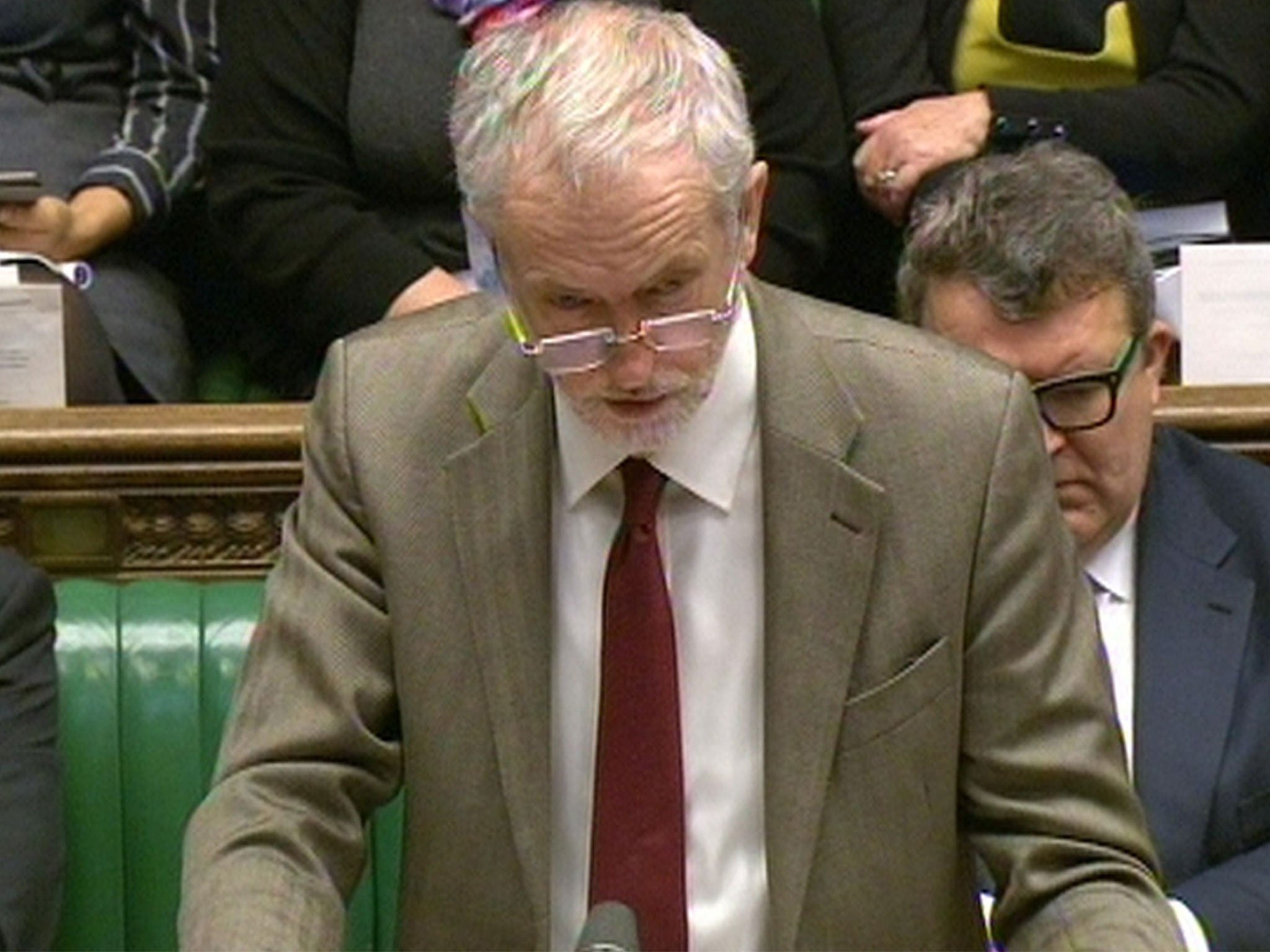

The noisy row over whether to back air strikes on Syria are part of a dynamic that has been in place since the moment Jeremy Corbyn was elected leader. The latest agonised clash appears to be part of a fast-moving story, yet nothing has changed. Corbyn has the support of most party members, but he has little backing in the parliamentary party and in the Shadow Cabinet. In their dissent, Labour MPs have little support in the membership. This is the fundamental problem; it is without a clear solution. They are in a battle.

Who can blame Corbyn for deploying his allies in the party membership when he is isolated at Westminster? Who can blame MPs for feeling threatened if local members turn on them?

Seeking culpability for the situation is futile. Corbyn cannot be blamed for winning a leadership contest. Labour MPs cannot be blamed if they genuinely disagree with their leader – although they should be held to account if they allow despair over Corbyn to cloud their judgement in relation to bombing Syria. But while the form of the division is unique, the scale of the divide is nothing new and nor is the intensity with which both sides make their case.

I could fill this newspaper with examples of Labour’s divisions over the past 50 years. For now, here are a few examples. In 1973, as opposition leader, Harold Wilson whipped his party into voting against the UK joining the Common Market. His move provoked a big rebellion led by the former Chancellor and Home Secretary, Roy Jenkins, a more substantial and experienced figure than rebels in the current Shadow Cabinet. During the 1970s and 1980s Labour was split on most epic issues, from continuing EU membership to nuclear disarmament and public ownership. When Tony Blair took the UK into war in Iraq more than 100 Labour MPs defied a three-line whip and a former Foreign Secretary, Robin Cook, resigned. Throughout the New Labour era, mythologised for its control freakery, there were intense policy divisions.

Labour’s big tent might be getting smaller in terms of supporters, but the canvas is impossibly wide. From Corbynite socialists to Cameronian Blairites, there is an ideological range that makes the Conservative Party appear a model of unity.

Divisions in both parties are largely hidden when a leader is popular and strong, or when leaders choose unity as their overwhelming objective, casting aside their own personal convictions. Blair could paper over the cracks because he was a winner. The many doubters suppressed their reservations as he led them from opposition and to continued power. The near unity in the cabinet over Iraq arose partly because Blair had won a second landslide election and, shamefully, ministers chose not to probe deeply believing they were acting “responsibly” by backing him. If Labour were currently 20 points ahead in the polls there would be less obvious disunity now.

Apart from aiming for intoxicating popularity, leaders have only one alternative route to unity: to be ruthlessly expedient, papering over divisions as a principled act of leadership. Former Labour leader Wilson has been more or less airbrushed out of political history, but he managed to win four elections leading a party as divided as it is today, presiding over a cabinet that included David Owen, Shirley Williams and Roy Jenkins to his right, and Tony Benn and Michael Foot to his left. The pragmatic wizardry required was exhausting. When Wilson resigned at 60, he looked well over 70 and suffered from paranoia that was largely justified. But he kept his party together with his “balanced” cabinets and shadow cabinets twisting and turning over policy.

Corbyn has called a free vote over Syria because has not been able to impose his will over MPs and, more specifically, his Shadow Cabinet, partly because they do not regard him as a winner even though he slaughtered their chosen candidates in the leadership contest. Nor can Corbyn be a Wilson-like leader because he has convictions which he holds deeply and over which he will not willingly compromise – admirable qualities in some respects, but problematic when those deeply held beliefs fuel division.

To my surprise, I believe that under such circumstances a formal split is possible. I am surprised because the risks are obvious and no dissenting MP plots toward a formal schism. The history of the SDP acts as a powerful warning and the current Shadow Cabinet dissenters are not in the same political league as those that formed the SDP. But for both sides a split is neater than the current nightmare. Corbyn could lead his movement for change without having to spend 90 per cent of his time managing an insurrectionary parliamentary party that is opposed to the movement and the change. Despairing Labour MPs would be liberated from their torment by starting afresh.

Alternatively, a Labour MP could grow into a Wilson-like figure and seek to be a unifying leader, bringing together a party that spans Corbynite socialists with a strong membership base and the Blairites represented in the media. Only political titans willing to age quickly need apply for that task.

What is certain is that the status quo is unsustainable. On this, both sides agree. There needs to be a cathartic battle that changes the nature of the current destructive dynamic between Corbyn and his MPs. A free vote on Syria might postpone the moment, but in its formal recognition of the division makes the cathartic battle more necessary than ever.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies