Wondering what your time is worth? £17 an hour – so don’t waste it listening to hold music

The cost of hanging on the phone to the taxman reached a disgraceful £66m last year, according to the National Audit Office

There’s something exquisitely painful about being forced to hang on the telephone, in vain, to speak to some company to rectify a mistake they’ve made. I experienced my own moment of torture recently when I was trying to get through to speak to someone at my pension administrator when I discovered I’d suddenly been locked out of online access to my funds.

I’d ring up (during work hours, because this was the only time the lines were open), wait on the phone for 10 minutes, and then give up because I needed to get on with some work. Then, later, I’d try again – only to be left hanging once more.

This went on for a week. It was only when I finally lost my patience and rang up the company’s press office to demand action that I finally managed to get a technician to ring me back and restore my access – not an option open to most people.

Why is it so painful? It’s not just the tedium, but the waste. Companies that don’t answer their phones promptly, for whatever reason, are time-wasters. They’re costing us time. But how much is that time that they waste worth?

It’s not a trivial question. One of the foundational concepts in economics is “opportunity cost”. That time I spent on hold trying to get through to my pension company could have been spent doing something economically productive. I didn’t lose any cash due to their incompetence, but it certainly cost me.

How much is your time worth? Around £17 an hour, according to the ready reckoner used by the tax authorities to value the time of people who fill in their returns.

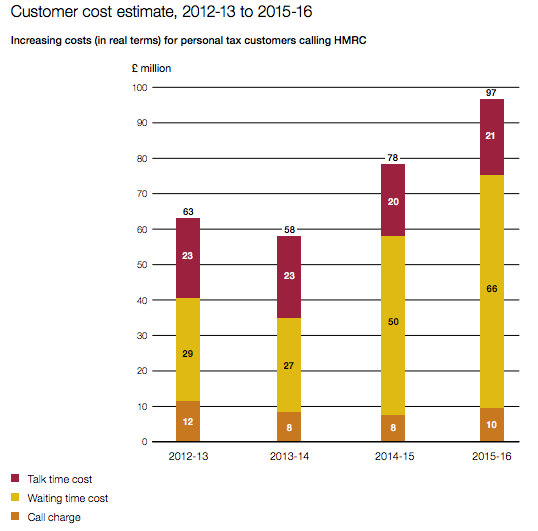

Last week the National Audit Office used this figure to calculate the total value of all HMRC customers’ time wasted waiting to speak to the authorities in 2015-16, after HM Revenue & Customs, like my pension firm, failed to ensure their phone lines were properly manned, resulting in massive phone delays.

According to the NAO, the effective cost imposed on the public came to a quite disgraceful £66m, more than double the cost two years earlier.

But how did HMRC make this £17-an-hour calculation? Through a lot of broad assumptions: they took the average annual full-time worker’s wage and applied a mark-up for a typical employer’s overhead costs.

But not everyone works in the formal workplace, so how do we value the time of those that don’t? The authorities took an estimate of the effective “wage” of people who look after children and do other activities that are valuable but don’t attract a salary. Then they derived the average hourly figure for a typical HMRC customer based on the proportion of the UK population in formal work and those who are not.

If this sounds a bit arbitrary to you, you’re right. It is. But it has to be done.

Rough estimates of the cost of people’s time are needed to guide policymakers. Think, for instance, of the cost of missed doctors’ appointments when NHS patients forget to turn up. No money changes hands, but the time of expensively trained medical staff has been wasted. That’s not free and people who keep missing appointments need to be sanctioned.

Bad policies can result when time value calculations are not done rigorously. The Government’s original high-speed Birmingham-to-London rail line cost-benefit calculations essentially assumed business travellers don’t do any work on trains. That boosted the case for the £40bn public investment to move people around the UK more rapidly.

But the idea that train journeys were unproductive time was always unrealistic, when people could work on laptops on longer journeys. And the proliferation of smart phones and wifi in recent years has made it even more flawed.

Yet we should remember that time cost calculations are also inherently speculative and inexact. Rude people push past you when you’re leaving a building. They act as if their time is worth more than your time. And that may actually be true. Higher personal productivity means higher opportunity cost.

The reality is that the opportunity cost will be different for different people. Averages, like those used by HMRC, will tend to conceal much.

And it’s not just our productivity at work that we need to consider when working out personal opportunity costs, but the value of our leisure time too.

We recently had some new shelves built in our house, and they needed to be painted. My wife and I had a choice: pay decorators £700 to do the job in a couple of days or do it ourselves bit by bit over a week.

We could afford the decorators. The choice was between several evenings relaxing versus saving some money by donning the overalls and wielding the rollers ourselves.

But the implicit question we were answering was: how much do we value our own leisure time? In case you were wondering, we painted the shelves.

Yet we must be careful over such calculations. Not everyone has the autonomy to “reveal their preferences” between leisure and work in this way. Restrictive working conditions can limit people’s choices.

If you feel you could be fired if you don’t agree to lots of overtime, then you’re not really revealing a preference by the hours you put in. People who can't get as many hours as they'd like due to the weakness of the wider economy, on the other hand, can skew calculations the other way.

Even when we have a choice, we’re not always strictly “rational” in a narrow sense either.

I once spent several days extracting money from a mobile phone network provider that had reneged on an introductory offer. The refund wasn’t remotely worth my time in chasing it, but I wasn’t going to let it go because I wanted to force the network provider to honour its commitment. Plus, I knew they were stalling on the assumption I’d eventually give up and go away.

Principles matter. I don’t care how high an individual’s productivity is, nothing gives them the right to rudely push past me, or jump the taxi queue. I suspect you feel the same.

On a less vexing note, there can be personal benefits from donating your time for free too, as many unpaid volunteers understand. Yes, they incur an opportunity cost, but they also get something intangible back: a gratifying sense of wellbeing from having contributed to the community.

Time most certainly has a value, as anyone who has been left hanging on a phone line by the taxman or an incompetent pension company will know. The opportunity cost is real, even if your wallet is no lighter, but don’t get too hung up on precisely how much an hour of your precious time is worth.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies