You should judge a person by how they peel a potato

Dave Hax's domestic tips are reminiscent of George Orwell's tea routine. The world might need revolution, but we like to sweat the small stuff

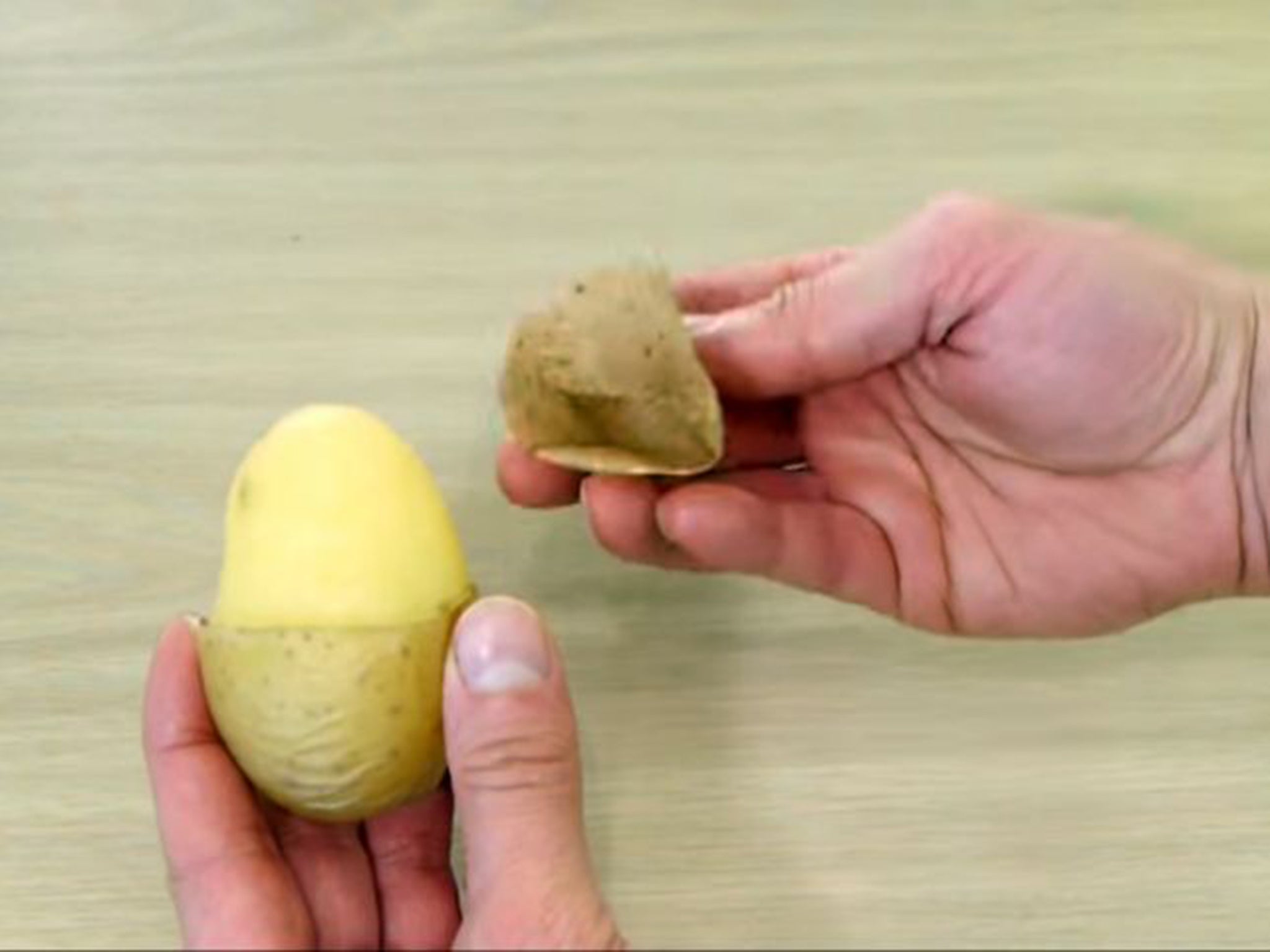

You may not have heard of Dave Hax. I confess to not having come across him myself until the moment, towards the end of last week, when the YouTube video in which he offers advice on the best way to peel a potato began to be picked up by the newspapers. For the record, Mr Hax has come up with the well-nigh revolutionary scheme of leaving most of the work until after the potato has boiled. Apparently, you simply score the unpeeled item around the middle with a sharp knife and remove from the pot 15 minutes later, whereupon the skin, once grasped between finger and thumb, slides away like a snake sloughing off its hide. No fuss, no need for a potato peeler, no cold hands and no dirty water clogging up the sink or splashing over your apron.

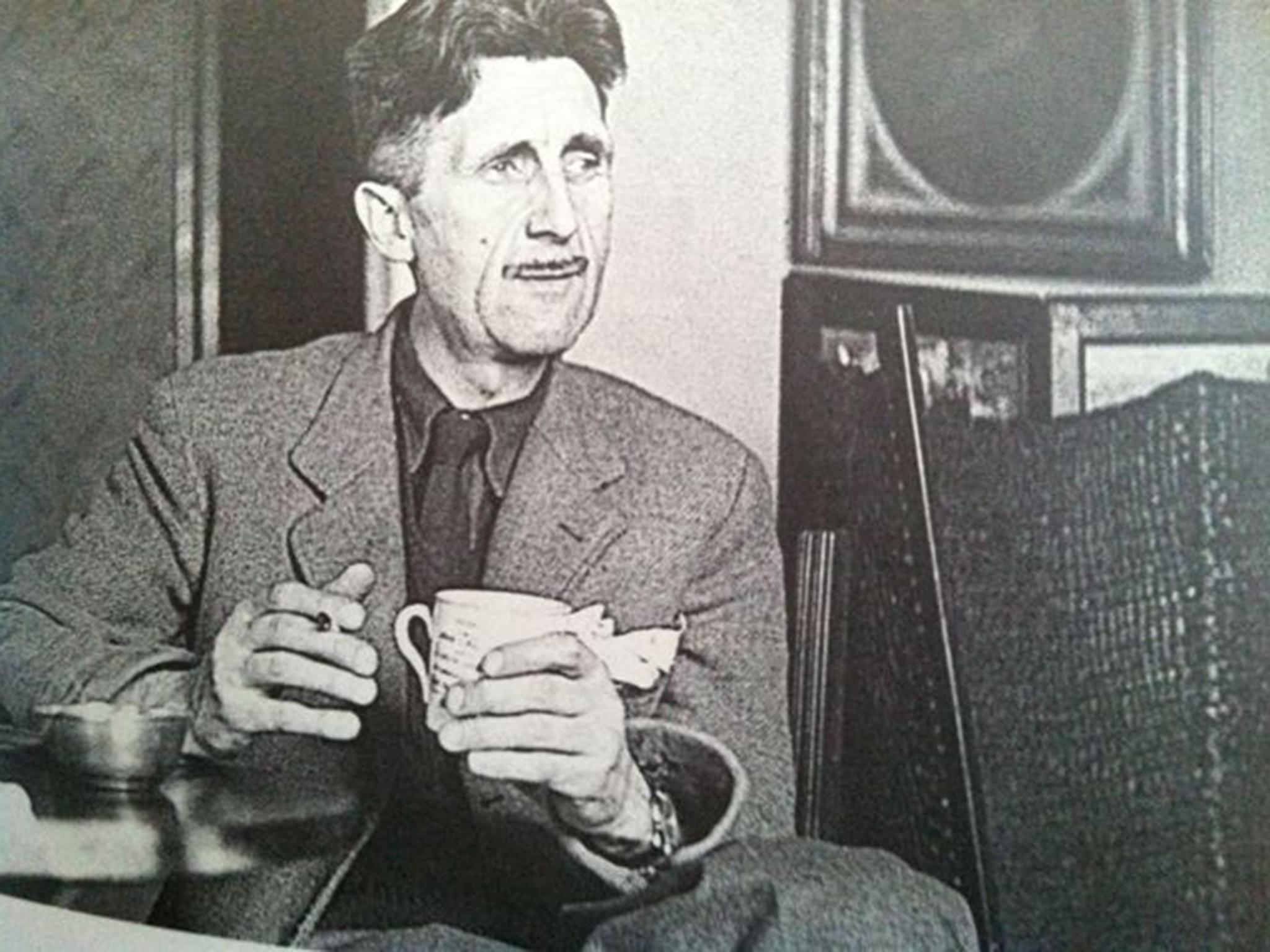

Two things instantly struck me about this ingenious exercise in food preparation. The first was the sedulousness of its approach. Mr Hax, it goes without saying, is a serious operator, a man who genuinely does believe that, having devised this culinary shortcut, it behoves him to share it with the rest of humanity – a grateful humanity, it appears, as the clip, released last weekend, had racked up two million hits by Thursday morning. The second was that it reminded me of something else. It took a second or two’s thought to establish that the thing it so strongly recalled to mind was not another online video but an essay entitled “A Nice Cup of Tea”, which George Orwell contributed to the London Evening Standard in January 1946.

Like Mr Hax, Orwell is deadly serious in his approach. He is – an infallible distinguishing mark of the dispenser of domestic advice – immediately proprietorial, refers straightaway to his “own recipe for the perfect cup of tea”, with the presumption that everyone else’s is worthless, notes there are no fewer than 11 outstanding points to be considered, of which at least four are “acutely controversial” and brooks no opposition from rival theory brokers. There follows a quite pitiless how-to guide to tea-making – what brand of tea to use, what kind of pot, degree of strength – replete with paragraph-long ventilations of what, in the tea-drinking world, are clearly burning issues.

Should one take the teapot to the kettle or vice versa? When should one add milk (Orwell maintains that his own argument, that of putting the tea in first and stirring as you pour, is “unanswerable”)? And how on earth can you call yourself a true tea lover by putting in sugar and destroying the flavour? And so, punctiliously and incriminatingly, on, over no fewer than 18 deeply committed paragraphs which, on most of the occasions that Orwell put pen to paper in 1946, would have been devoted to the state of the Labour Party, the post-war international situation or early drafts of Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Clearly in Dave Hax, Orwell would have found a kindred spirit, for the subtext of Hax on potato peeling is precisely that of “A Nice Cup of Tea” – the profound importance to the specimen human being of supposedly trivial things, and the psychological satisfactions to be derived from imposing your own private patterns upon them. Needless to say, these modus operandi extend deep into the subsoil of popular culture. Many of them, as these illustrations demonstrate, are about food – how to make hot buttered toast, how to boil an egg, how to make coffee without burning it – but an equally large percentage are about household maintenance. Even today, for example, the correspondence columns of magazines such as The Lady positively thrum with advice on how to get the grease off your antimacassars and arrange three carnations, two roses and a tulip advantageously in a water jug.

There are several wider cultural points to be made about these determined efforts to get all the dirt off fork tines or polish your shoes in such a way that you can see your face in the toecaps. The first is that the general material betterment of the past 150 years or so has made no difference to the mental processes that propel them. An Edwardian housewife who wrote to a weekly magazine wanting to know the best way to restitch a torn double sheet or how to preserve her chutney against mould was, by and large, driven by economic necessity. The modern-day antimacassar-cleanser, on the other hand, could easily afford a new one, while knowing that this isn’t the principle at stake: what matters is the thrill of the chase, the pleasure of a problem solved, and the rituals that this problem-solving invariably brings in its wake.

The second is that this relish of trivia, infinitesimally marginal ways of smoothing your path through life, has nothing to do with an innate practicality or a determination to get value for money out of the things before you (although Orwell, writing at a time of rationing, notes rather proudly that his methods, if followed to the letter, will wring 20 cups out of a 2oz packet). Rather, it is to do with mindset. I, for example, am physically inept, cannot drive a car or mend a bicycle puncture, and once nearly electrocuted my wife with a faultily rewired plug. On the other hand, I could happily star in an instruction video on the best way to pluck a pheasant (you start at the lower end of the breast, pulling the feathers away from you so as not to break the skin), disembowel a crab or freshen up a less-than-clean jacket by covering it with strips of Sellotape.

Even more crucial than whether these methods actually work is their philosophical significance. For the real importance of this outlook on life, it goes without saying, is that it runs directly against one of the great motivating impulses of the modern age, which is its utilitarianism. A truly serious person, the argument goes – one of those purposeful titans for whom time is money and light nonsense unthinkable – couldn’t care less how his, or her, tea is made. The drink itself takes precedence over the manner of its preparation. Similarly, if wanting to eat a pheasant, he or she will buy it ready plucked (and with all the shot tidily removed) from a game dealer – a highly logical and labour-saving approach, no doubt, but one which instantly removes all thought of pleasure from the exercise.

All this ignores the fact that half the satisfaction in life comes from activities which have only a very marginal effect on the business of living. After all, what does it matter in the end how one peels a potato or prepares a cup of tea? The potato will taste exactly the same and even a cup of tea brewed on the Orwell principle will not differ very greatly from PG tips in a Styrofoam cup. On the other hand, it could be argued that worrying, or some-times only affecting to worry, about this kind of minutiae is an essential part of the humanist project, something that makes us the people we are. Naturally, there is a fine line to be drawn between the spirit of earnest quasi-scientific inquiry and sheer whimsicality, and it would be very easy, if one had the inclination, to produce a savage parody of Mr Hax’s endeavours in the potato peeling department. But you have a feeling that Orwell, had he somehow been granted access to YouTube, would have been enchanted.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies