China and the beginning of Coronavirus: 25 days that changed the world

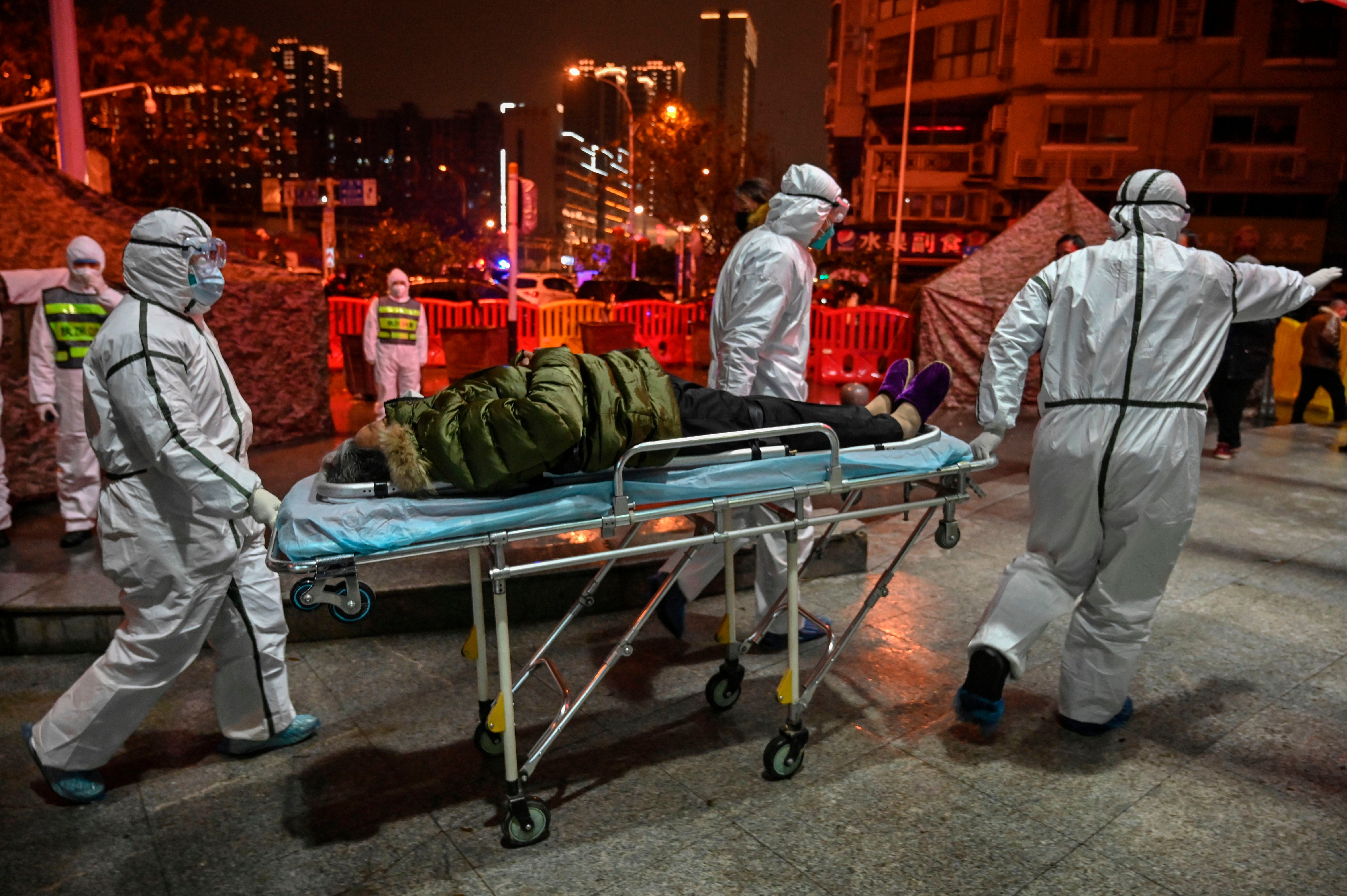

When authorities in Wuhan first started to tackle a deadly virus in their city, those early days would change the world, write Chris Buckley, David D Kirkpatrick, Amy Qin and Javier C Hernandez

The most famous doctor in China was on an urgent mission.

Celebrated as the hero who helped uncover the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic – or Sars – 17 years ago, Zhong Nanshan, now 84, was under orders to rush to Wuhan, a city in central China, to investigate a strange new coronavirus.

China’s official history now portrays Dr Zhong’s trip as the cinematic turning point in an ultimately triumphant war against Covid-19, when he discovered the virus was spreading dangerously and sped to Beijing to sound the alarm. Four days later, on 23 January, China’s leader, Xi Jinping, sealed off Wuhan.

That lockdown was the first decisive step in saving China. But in a pandemic that has since claimed more than 1.8 million lives, it came too late to prevent the virus from spilling into the rest of the world.

The first alarm had actually sounded 25 days earlier, last 30 December. Even before then, Chinese doctors and scientists had been pushing for answers, yet officials in Wuhan and Beijing concealed the extent of infections or refused to act on warnings.

Politics stymied science, in a tension that would define the pandemic. China’s delayed initial response unleashed the virus on the world and foreshadowed battles between scientists and political leaders over transparency, public health and economics that would play out across continents.

This article, drawing on Chinese government documents, internal sources, interviews, research papers and books, including neglected or censored public accounts, examines those 25 days in China that changed the world.

Scientists and private laboratories in the country identified the coronavirus and mapped its genes weeks before Beijing acknowledged the severity of the problem. Experts were talking to their peers, trying to raise alarms – and in some cases, they did, if at a price.

“We also spoke the truth,” says Professor Zhang Yongzhen, a leading virus expert in Shanghai. “But nobody listened to us, and that’s really tragic.”

As political hostilities erupted between China and the United States, scientists on both sides leaned on global networks built up over decades and sought to share information, with leading experts recognising early on that the virus was probably contagious among humans.

On 8 January, the head of the Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), George Gao, became emotional after acknowledging that danger during a call with his American counterpart, Robert Redfield, according to two people familiar with Redfield’s account of the call.

Yet neither Redfield nor Gao, each constrained by politics, signalled a public alarm. In Beijing, top health officials had received ominous reports from doctors in Wuhan and had sent two expert teams to investigate. Yet they lacked the political clout to challenge Wuhan officials and held their tongues in public.

To a degree, Zhong’s trip to Wuhan was less medical than political. He already knew the virus was spreading between people; his real purpose was to break the logjam in China’s opaque system of government.

Officials ultimately got control, both of the virus and of the narrative surrounding it.

Chinese diplomats argue that the country’s record of stifling infections after the Wuhan lockdown has vindicated Xi’s strong-arm politics, even as the government has airbrushed over the early weeks, when decisive action could have curbed the outbreak. One early study projected that China could have reduced the total number of cases by 66 per cent had officials acted a week earlier. Action three weeks earlier could have dropped the caseload by 95 per cent.

China’s reluctance to be transparent about those initial weeks has also left gaping holes in what the world knows about the coronavirus. Scientists have little insight into where and how the virus emerged, in part because Beijing has delayed an independent investigation into the animal origins of the outbreak.

‘Everyone saw it on the internet’

On 30 December, after doctors in Wuhan came across patients with a mysterious, hard-to-treat pneumonia, city authorities ordered hospitals to report similar cases. By policy, the hospitals should have also reported them directly to the national CDC in Beijing.

They did not.

Barely 12 minutes after the internal notice was issued, though, it spilled onto WeChat, China’s nearly ubiquitous social-media service, and a later second internal notice on patient care also quickly spread online until talk of a mysterious pneumonia outbreak reached Gao, the Oxford-trained virus expert who heads the CDC.

“Wasn’t it all being talked about on the internet?” Gao said when asked about how he learned about the Wuhan cases. “Everyone saw it on the internet.”

Late that night, the Chinese National Health Commission ordered medical experts to rush to Wuhan in the morning.

Hours later, the medical news service ProMED issued a bulletin to global health professionals, including the World Health Organisation.

In Wuhan, the outbreak seemed concentrated at the Huanan seafood wholesale market. A week earlier, local doctors had sent lung fluid from a sick 65-year-old market worker to Vision Medicals, a genomics firm in southern China. It found a coronavirus roughly similar to Sars. Two more commercial labs soon reached the same conclusion. None dared go public.

Vision Medicals sent its data to the Chinese Academy of Medical Science in Beijing and dispatched a top executive to warn the Wuhan Health Commission.

The Beijing team that arrived in Wuhan on the last day of 2019 was quickly informed of the laboratory results.

At that point, the Wuhan government had publicly confirmed that city hospitals were dealing with an unusual pneumonia but denied it was potentially contagious.

At the same time, the National Health Commission told the commercial labs to destroy or hand over samples with the virus and ordered that research findings be published only after official approval. The head of the Guangdong Health Commission, under orders from Beijing, led a team to Vision Medicals to seize its sample.

More than 500 miles to the east, Zhang, a leading virologist at the Shanghai Public Health Clinical Centre, was very worried.

Like several other Chinese labs, the team there had cracked the virus’ genetic code and concluded that it could be contagious. Unlike the other labs, Zhang felt a duty to publish the information to help researchers work on tests, treatments and vaccines.

After the team finished sequencing the virus on 5 January, his centre internally warned leaders in Shanghai and health officials in Beijing, recommending protective steps in public spaces.

He also prepared to release the data, a step that took on added urgency after he visited Wuhan to speak at a university on 9 January. That day, the government confirmed the new disease was a coronavirus, but officials continued to play down the potential danger.

On 11 January, Zhang was about to board a flight to Beijing when he received a call from his longtime research partner, Edward Holmes, a virus expert at the University of Sydney.

By now China had reported its first virus death. Zhang had already submitted his sequence to GenBank, a vast online library of genetic data.

Holmes prodded his friend. Look at the rising number of cases in Wuhan, he said.

It was a decision that only Zhang could make, Holmes told him. Releasing the data risked offending health officials who were intent on controlling information.

“I told him to release it,” Zhang said.

Soon the data was up on a virology website.

Some two-and-a-half hours later, Zhang landed in Beijing. When he turned on his phone, messages poured in.

“Getting it out quickly was the only aim,” Holmes said. “We knew that there would be consequences.”

Broken partnership

Redfield, director of the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, was an old friend of his Chinese counterpart, Gao. The two men had spoken after the ProMED alert, but Gao had insisted that the virus had spread only from animals at the market, not from person to person.

But now, on 8 January, Gao said the virus had infected medical workers and was jumping between humans.

Politically, it was a perilous situation for both men.

As its trade war with China escalated, the Trump administration had all but eliminated a public health partnership with Beijing that had begun after the debacle of Sars and was intended to help prevent potential pandemics. By pulling out, current and former agency officials say, Washington cut itself off from potential intelligence about the virus and lost a chance to work with China against it.

Under the partnership, teams of American doctors were stationed in China and, over time, helped train more than 2,500 Chinese public health staff. Another US programme in the country, called Predict, sought to spot dangerous pathogens in animals, particularly coronaviruses, before they could leap to humans.

Yet in July 2019, without public explanation, the US pulled out the last American doctor inside the Chinese CDC. A separate Beijing office of the US CDC closed months later. The Predict program was also suspended.

A toothless watchdog

On paper, Ma Xiaowei, director of China’s National Health Commission and the most powerful person in the country’s medical bureaucracy, wielded formidable resources to stop the virus in Wuhan.

In practice, his hands were tied.

In the Communist Party hierarchy, he stood at the edge of the elite. Outside Beijing, disease control officials often took their cues from local overseers, not Ma.

But on 8 January, Ma dispatched a team to Wuhan. Officials there claimed that no new cases had been detected for days, and the new Beijing team did not publicly challenge that assessment.

Ma was hardly oblivious to the rising risks. A Wuhan tourist visiting Thailand had become the first case confirmed outside China. The National Health Commission called together medical officials across China on 14 January for a video meeting – kept secret at the time – that laid out precautions against the virus.

Afterward, the commission sent out an internal directive: 63 pages that advised hospitals and disease control centres across China about how to track and halt the new virus – and seemed to assume it was contagious.

Yet the instructions hedged on the key issue. There was “no clear proof in the cases of human-to-human transmission among the cases”, one section declared.

In mid-January, Xi presided over a meeting of the country’s two dozen top officials. There was no mention of the coronavirus, at least in the official summaries then and since.

On 18 January, Ma enlisted Zhong to lead a third delegation to Wuhan.

There, Zhong learned from former students that “the actual situation in Hubei was far worse than was public or in news reports,” he told a Guangdong newspaper.

Yet officials still insisted the outbreak was manageable when the governor of Hubei province, Wang Xiaodong, received Zhong’s team in a hotel conference room.

Finally, one of the officials acknowledged that 15 medical workers in Wuhan Union Hospital were likely to have been infected, an admission of human-to-human spread. It was all Zhong needed, and his team rushed to Beijing.

The visit gave Ma, the top health official, political cover to press top leaders for urgent action.

The next morning, Zhong went to the Chinese Communist Party leadership’s walled compound, Zhongnanhai. Xi was away in southwestern China, and prime minister Li Keqiang listened as the experts warned that the virus was spreading.

Three days later, China had confirmed 571 cases of the coronavirus, although experts estimate the real number was many thousands. Xi closed off Wuhan, a city of 11 million people.

Rewriting history

Eleven days later, Xi was facing a political crisis.

China’s internet echoed with fury over Li Wenliang, a Wuhan doctor who was reprimanded by police after trying to alert colleagues to the coronavirus. Li now lay in a critical care unit after contracting the virus. Emboldened Chinese journalists had produced searing accounts of missteps and lies in the previous weeks.

Under fire, Xi defended his record at a Politburo meeting on 3 February, asserting that he had been on the case early.

Infections and deaths kept rising. On 7 February, Li died. Questions spread in China and abroad about Xi’s grip on power.

Eager to show that Xi remained in command, propaganda officials released his Politburo speech from early February – except that ignited even more questions.

Until then, Xi’s earliest known comments on the crisis were on 20 January. But in his speech, Xi claimed he had given internal instructions about the outbreak as early as 7 January, before China had officially announced that the disease was a coronavirus.

On China’s internet, people asked why they had not been warned sooner, given that the issue was urgent enough to go to Xi’s desk. And why, they asked, were Xi’s precise instructions not made public?

But Xi’s speech foreshadowed what was to come – rewriting the history of the crisis even as it was happening.

“We must actively respond to international concerns,” Xi told leaders, “and tell a good story of China’s fight against the outbreak.”

© The New York Times

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies