Why many Italians fear the prospect of Silvio Berlusconi as president

Italy’s former prime minister has ramped up his media campaign ahead of next week’s presidential election but his criminal and often sordid past has alienated much of the public, writes Sofia Barbarani in Rome

From loved-up social media posts with his partner to a full-page newspaper advertisement extolling his achievements, Italy’s billionaire media tycoon Silvio Berlusconi has been enjoying the limelight once again ahead of next week’s presidential elections.

It is no secret that Mr Berlusconi has been eyeing the country’s top job for some time, and the 85-year-old former prime minister knows how to market himself to the public.

He has been making a concerted effort to boost his own image in the lead-up to 24 January, when just over 1,000 lawmakers and regional delegates will vote for president Sergio Mattarella’s replacement.

Italy’s president – elected for a seven-year term – has a largely ceremonial role, although they are often a point of reference in times of national emergencies or political strife.

While there are no formal candidates for the presidential election, Mr Berlusconi has mobilised his media empire behind his bid in a campaign reminiscent of those that helped him win three national elections.

He has shown off his girlfriend, 32-year-old politician Marta Fascina, on Facebook, while the recent advertisement in his family-run newspaper Il Giornale lists 22 supposed qualities and successes, including “ending the Cold War” and “being the president of the club (AC Milan) with the most wins in international football”.

A dominant public figure and the longest-serving post-war prime minister in a country where governments have typically tumbled like dominoes, some 18 per cent of Italians interviewed by polling company SWG last week want Mr Berlusconi at the wheel. Just over half said they are rooting for prime minister Mario Draghi to become president.

Analysts, journalists and several citizens told The Independent they feared a Berlusconi presidency would tarnish the country’s political decorum, sully its reputation abroad, and could even spur the far-right.

Ultimately, the decision of who to elect president rests with parliamentarians and local officials, not ordinary citizens.

But while pollsters suggest that Mr Draghi is the likeliest winner, Mr Berlusconi received a powerful show of support last week when the far-right parties Brothers of Italy and the League gave him their backing.

Even Matteo Salvini of the radical right and populist Lega party, whose relationship with Mr Berlusconi has been shaky, expressed his approval.

The statement, issued by the so-called “centre-right” bloc, described Mr Berlusconi as “the right person for the high office during this difficult juncture, with the authority and the experience that the country deserves, and that Italians expect”.

This partnership between the parties, coupled with a Berlusconi presidency, could result in the emboldening of the Italian far-right, according to experts.

“Even if Berlusconi has to some extent and rather surprisingly married a moderate and liberal stance, a Berlusconi Presidente della Repubblica would further allow the dangerous phenomenon of mainstreaming of the radical-right in Italy,” says Valerio Alfonso Bruno of the Centre for Analysis of the Radical Right (CARR).

This, in part, is the reason why many Italians are against the idea of Mr Berlusconi returning to power.

They also cite his criminal endeavours – from tax fraud to a conviction for paying an underage girl for sex that was later overturned – not to mention his divisive politics and embarrassing antics such as the notorious “bunga bunga” parties he used to host.

“How can a person who was sentenced to four years in prison for tax fraud, false accounting and embezzlement become president of the Republic?” said a journalist who worked at the Berlusconi-owned Canale 5 TV channel in the 1980s and knew him well.

“We are paying for the absolute degradation of our political class, which reflects the degradation of a large portion of Italian society,” said the journalist, who asked to remain anonymous for fear of repercussions.

Although Mr Berlusconi seemingly lacks broad support among the political elite, his victory is not yet out of the question.

Italian journalist and author Franco Mimmi said such an outcome would not be so surprising given “the very low level of some leaders” in Europe, pointing to Boris Johnson as an example.

In Italy, members of parliament, including Annagrazia Calabria of Berlusconi’s party Forza Italia, have praised the media tycoon publicly, referring to him as a “statesman who has given a voice to millions of Italians” and “dedicated his entire life to the service of the country”.

Abroad, Antonio Lopez, a member of the right-wing European People’s Party Group in the European Parliament, has also expressed support. “Berlusconi at the Quirinal (presidential palace) would be a double victory for Italy and for Europe,” he said this month.

Nonetheless, many Italian citizens have been vocal in their opposition.

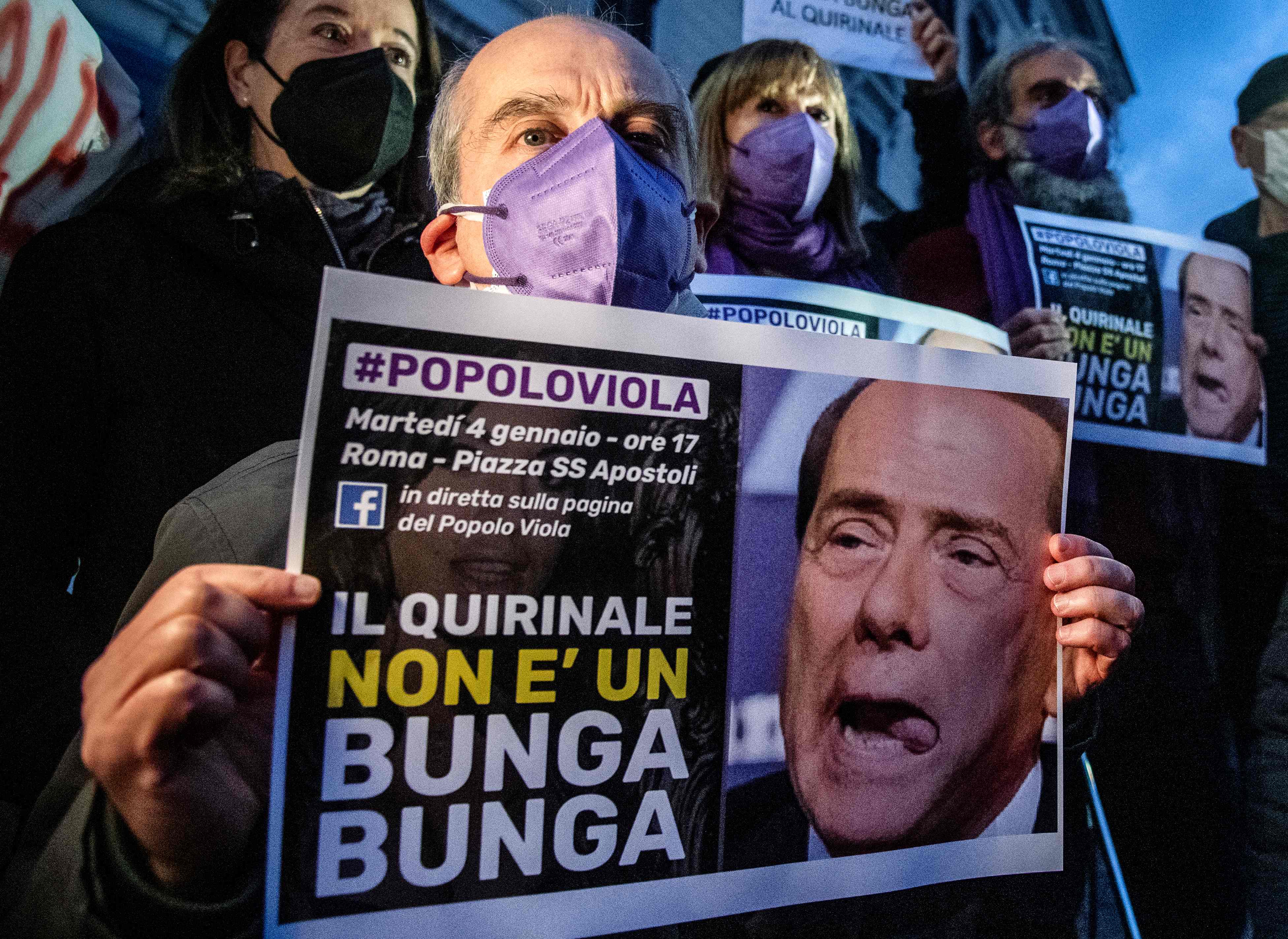

Earlier this month, hundreds of people took to the streets of Rome to protest against Mr Berlusconi, chanting “the Quirinal is not a bunga bunga”.

The organisers of the march called on parliamentarians to “prevent the most divisive and most inappropriate name from being indicated as the representative of our most important institution”.

Similarly, left-wing newspaper Il Fatto Quotidiano launched an online petition last month to rally against the election of Mr Berlusconi.

In an open letter, the paper’s current and former editors-in-chief asked members of parliament not to “vote … talk… or even think about” putting him in power.

Italy’s increasingly disgruntled younger generations say that seeing Mr Berlusconi at the helm would be a fitting outcome for a country that has already debased itself.

“A country as ridiculous as Italy cannot be represented internationally and institutionally by a person who isn’t ridiculous,” said János Chiala, a 37-year-old photojournalist from the southern region of Puglia.

Like so many young Italians over the course of the past two decades, Mr Chiala was forced to shut down his small business recently and began to pack his bags in search of a less dysfunctional country.

A report from 2017 put the number of Italians who left between 2008 and 2016 at more than half a million. Mr Chiala will likely soon join them in France.

“[Berlusconi’s election] would be a positive thing for us because, maybe, it might lead some people to reason about the kind of level that Italy is reaching,” he said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments