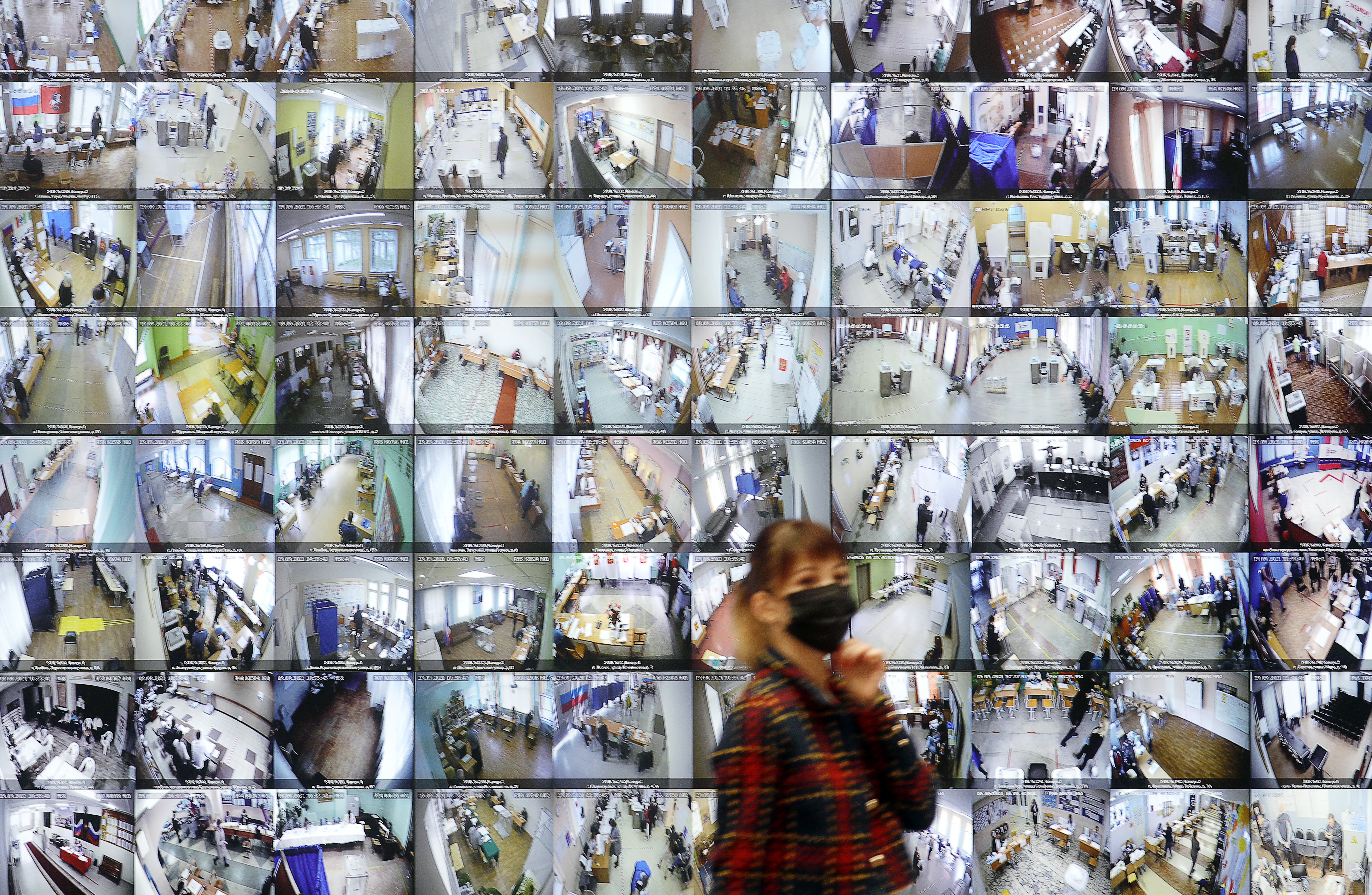

Russian election: How a visit to a polling station led to my personal data being leaked online

Reporting on allegations of elections manipulation, 450 miles east of Moscow, led to a breach of my personal data, writes Oliver Carroll in Osinovo

I knew I was reporting a sensitive election patch. I didn’t imagine it would end with my personal data being leaked on the internet in an apparent act of intimidation.

Polling stations in Tatarstan, 450 miles east of Moscow, are where the Kremlin’s majorities are traditionally made. The region reliably posts some of the nation’s most remarkable returns. In 2016, for example, it claimed 79 per cent turnout with 85 per cent voting for the Kremlin party United Russia (against national figures of 48 per cent and 54 per cent).

While authorities might suggest it’s the result of an ecstatically content electorate, there are competing explanations.

Polling station 2822 in Osinovo, on the border between capital Kazan and rural Tatarstan, is in a sweet spot for possible election manipulations. It’s far enough from the city to make it difficult for opposition forces to reliably send many monitors. Mentally, it’s also a world away from urban values of electoral democracy, meaning the local election officials are generally more obliging.

Such considerations – and reports of official turnout three times above that which independent monitors were observing – were the reason I headed there on Saturday, the second day of voting in legislative elections.

It didn’t take long before the games started.

After arriving at the polling booth, I was accredited, but only reluctantly, by the chair of the election commission. The official took my passport, made a record –and, crucially, a photocopy – and then asked to see a copy of my migration documents (this isn’t even a legal requirement). She departed to the adjacent room for what appeared to be a set of urgent phone calls.

In the meantime, I began talking to Gulnaz Ravilova, the young candidate from the democratic Yabloko party, who first made the claims of fraud.

The 22-year-old is, as far as the local authorities are concerned, a pesky “extremist” who doesn’t take the hints. Politically active since the age of 14 – she participated in protests against killing stray animals ahead of the 2013 World University games in Kazan – Ms Ravilova has refused to step down even while facing prosecution over alleged links to the now criminalised structures of Kremlin foe and opposition leader, Alexei Navalny. She denies the charges.

We called the chair of the elections committee and demanded a recount and to see the voting records. She refused to talk

She told me what she saw on the first day of voting on Friday. Under election rules, the chair of the commission is obliged to provide turnout figures twice – at 3pm and 8pm. When she did so the first time, the numbers roughly corresponded with the picture Ms Ravilova and her colleagues had recorded. But the 8pm returns – 617 voters – were over three times the 185 believed to have voted.

“Our jaws dropped when we saw the evening figures," said Ms Ravilova. “We called the chair of the elections committee and demanded a recount and to see the voting records. She refused to talk.”

The three-day voting has introduced changes in the electoral process from previous years. Now, at the end of each day, votes are sealed into “safe envelopes”, before being moved to a supposedly secure locked safe.

A second safe contains the voting papers and records of who voted. The particular issue at polling station 2822 was that this second “safe” was held out of view of cameras in an adjacent room. Another concern was that it wasn’t a safe in any usual sense of the world, but a rickety wooden cabinet that could easily be opened if required.

After complaints and reports in national newspapers, the regional elections commission ordered the safe to be moved into the main room on Saturday morning. It isn’t clear what exactly happened next. Opposition monitors say no one was prepared to move the safe, so it appears they did it themselves. A monitor from the ruling United Russia party told The Independent the opposition candidates moved the safe "violently," causing part of the door of the cabinet to fall from its hinges.

I was in the process of comparing notes, reporting and talking to the various parties, when half a dozen serious-looking men appeared in the room.

The men were wearing almost identical conspicuously inconspicuous black jackets, blue jeans and pointy leather shoes. They looked in my direction, motionless and emotionless. I was told one of the men is the deputy head of the shadowy “Centre E”, a local security body charged with combatting extremism but usually more interested in matters of dissent.

One by one, other strange visitors began filling the voting room. They included new “monitors”, also stocky looking men, identifying from the “Communists of Russia” party, a fake spoiler party reportedly set up by authorities. Then a woman from United Russia arrived. They smiled and nodded to one another, and then to the group of men now huddled in the adjacent room.

“You’re not going to stage some tricks, are you?” Ravilova asked one of the bulky looking men. “Girl, I swear on my heart, I won’t,” came his almost flirtatious response. “And what about you? Will you be staging tricks?”

The next visitor to enter the room – a tall, young woman – made a beeline directly for me. She identified herself as a reporter from Tatar Info, a state media agency. “I am here to speak you, Oliver. You want to speak me in English? In Raw-shun?” I asked how she could possibly know my name. She offered no response.

Over the course of Saturday, the opposition team made several unsuccessful attempts to inspect voter records. The drama reached a crescendo just before polling closed at 8pm. Unannounced, an independent election official turned up, claiming to have a mandate from the regional elections commission. He declared his intention to film the opening of election boxes and the voter count.

The man’s story may well have been genuine, but he didn’t have the papers to prove it. So he was blocked by the army of loyal “election monitors”, who formed a wall between him, his camera, the urn and officials. Scuffles then began to break out; at one point it seemed everyone in the room was shouting. The uninvited official then attempted to sneak a way through the scrum for him and his GoPro.

“Police! Police!” shouted one of the Kremlin-loyalist monitors. “He’s touching my bottom!”

An elderly woman of about 60 with red hair and large silver earrings hissed at the bustling crowd. “And they say we even think about letting them close to power,” she said, referring to the opposition. The woman is one of the supposedly independent members of the polling station’s official election commission.

Just as the dramatic day appeared to be reaching a natural conclusion – the process of tipping papers into safe envelopes for overnight safekeeping – I was alerted to a series of alarming social media posts.

One post showed a picture of my own photocopied passport released on a public channel on the Telegram messenger app, complete with personal data. Another suggested I had arrived in Tatarstan to blacken the reputation of local elections. The channel is reportedly connected to local authorities.

There appeared to be only two possible sources for the leak: my hotel, which copied the passport to complete migration papers, or the committee chair and associated security officials. But the copy taken by the hotel, which I have since inspected, is of a much higher resolution than the one published online.

It’s hard to understand the precise logic driving the release of my personal data, falling as it does outside of the range of rational, moral and legal frameworks. Perhaps it was an attempt to alert people to watch out for me. Perhaps it was a local interpretation of an obvious trend in Moscow: that foreign journalists are not as welcome as they once were. Perhaps it was frustration at seeing part of an important vote-manufacturing machine interrupted.

On the latter front, my unexpected visit may well have played a disruptive role. On day two of elections, chair Guzel Rubanova announced an evidently reasonable 139 voters had been registered – almost exactly the numbers recorded by independent monitors, and less than a quarter of the disputed number posted the day before.

The reduced figures didn’t make much of a dent into turnout across Tatarstan. That went up to an eyebrow-raising 57.5 per cent, the sixth best figures of 85 regions nationwide. Who knows where we will be at 8pm later today, Sunday, the moment that voting in Russia’s already highly controversial elections closes.

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks