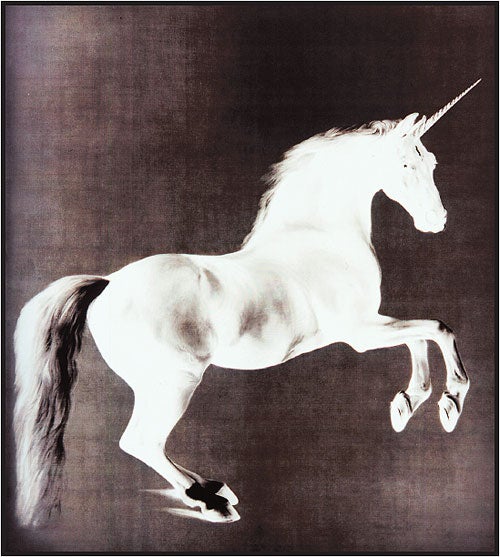

Wallinger, Mark: Ghost (2001)

The Independent's Great Art series

Also in this article:

About the artist

William Camden, the 17th-century English antiquary, defined an anagram: "the dissolution of a name, truly written, into the letters as its elements, and a new connection of it by artificial transposition, without addition, subtraction, or change of any letter..."

Without change: the whole power of the anagram lies in the fact that nothing is made up. A word or name is taken, and simply rearranged, so as to produce, out of itself, another word or name, which feels like its latent inner truth. A good anagram has an aspect of destiny though, equally, you can dismiss it as an insignificant coincidence.

Something similar can be done with visuals. An existent image can be taken, and subjected to some simple, strict and transparent operation, so as to produce another image out of it. There is Mark Wallinger's Ghost, for example. This contemporary lightbox picture takes a famous old painting of a mortal horse and without at all reworking it utterly transforms it, into an otherworldly unicorn.

The existent image is George Stubbs' huge and extravagant horse painting of 1762, Whistlejacket. It was commissioned as a royal equestrian portrait in a landscape. But when the commission fell through, Stubbs completed it without king or country just a grand dark-bay stallion, with a wild look, rearing in a formal "levade", against an entirely blank light-brown background.

Wallinger, retaining the original size of the painting 9ft high subjects it to three simple operations. First, it's turned into a black-and-white photograph. Second, it's turned into a negative, the tonality reversed. Third, the horn of a narwhal whale (traditionally identified with the horn of the unicorn) is montaged onto its brow.

Abracadabra, hey presto! The empty background becomes a deep night. The dark, suddenly-rearing horse becomes a lightning-struck apparition. And the reversed shading of its body gives it a weird and spectral substance. That's the general effect but several further felicities emerge, as small details of Whistlejacket come to new life under this transformation.

The stallion's dark, flared nostrils glow as if filled with molten white heat. Its fine-combed mane becomes a ridge of licking smoky flames. Its front hooves glow like horseshoes from the forge. And the abrupt little darts of shadow, with which Stubbs attached the two back hooves to a notional ground, become fiery jets.

The metamorphosis is rich in implication. Translating naturalism into supernaturalism, Ghost synchs the two dominant strains of English art: Stubbs' observational study is shown to hold within it a spiritual vision by Blake or Fuseli. The work resembles one of those conservatorial X-rays of an Old Master painting, which reveals the image that lies hidden beneath. It also suggests spirit photography, the camera revealing the invisible.

Sustaining all these "revelation" effects is the fact that the found image has not been substantially altered or repainted. The work asks you to recognise the Stubbs original, and to see that it has only been developed like a print in a darkroom so as to disclose this new image that was within it all along. Like a successful anagram, Ghost seems somehow inevitable; or on the other hand, wholly fortuitous; a total stroke of luck.

Of course, the "anagram" is not quite perfect. Something has been added: the narwhal horn. The ghostly unicorn isn't simply released from the worldly horse. It's given this extra nudge. A purist might oppose the addition, or say that if the effect depends on it, then the effect is illegitimate. And it's true that the full effect probably does depend on the horn. Imagine it away, and the unearthliness of the vision doesn't quite click. It needs that little nudge.

But in this case, the impurity is justified. It only intensifies Ghost's ambiguous impact. The blatant addition of the horn is upfront faking, an explicit bit of hocus-pocus, which stresses the deliberate and far-fetched nature of this transformation. On the other hand, once it is added, it doesn't look awkwardly extraneous, but undeniably true and natural, as if the great horse was born to bear this magical appendage.

The artist

Mark Wallinger (born 1959) is the most gifted conceptual artist of his generation. Working across media, both learned and populist, with unflagging verbal and visual invention, his abiding concerns are belief and disbelief, whether political or religious. He is best known for his statue of Jesus in Trafalgar Square, Ecce Homo. He often presents situations where something can be transformed into its opposite through a simple change or re-reading as if by a sudden leap, or loss, of faith. Many of his highly diverse works also show an interest in horses and horseracing. He once owned a racehorse named A Real Work of Art. He has appeared as a pantomime horse. He has just won the 2007 Turner Prize.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks