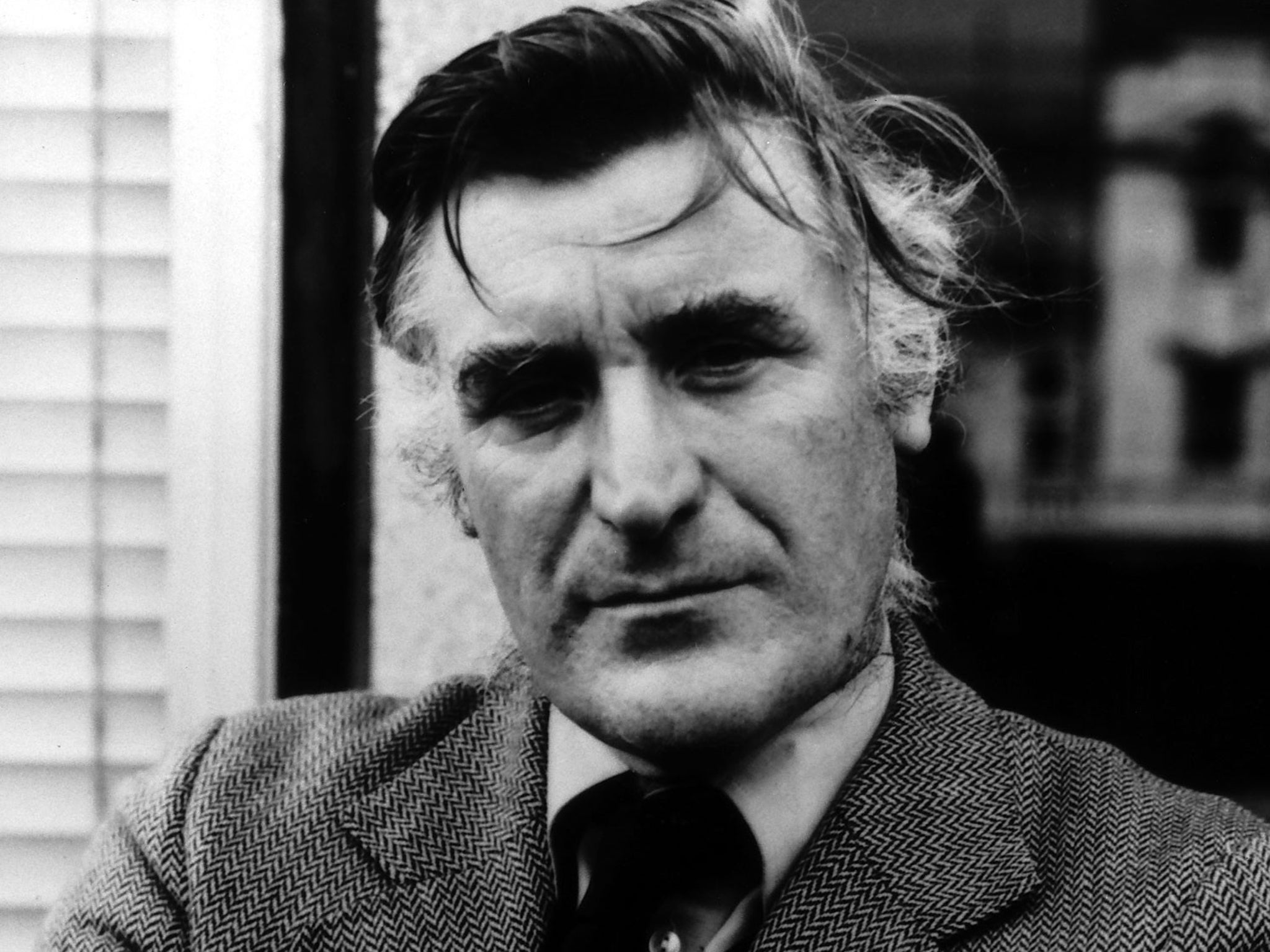

Sir Jonathan Bate on his controversial new biography about poet Ted Hughes

'This was the book I was born to write'

Sir Jonathan Bate does not come across like the type to court controversy. Softly spoken, elegant and eminently reasonable, the 57-year-old writer and academic seems perfectly at home in the autumnal, pre-term hush of Worcester College, Oxford, where he has been Provost since 2011. In addition to running the college and circumnavigating Oxford’s byzantine internal politics, Bate’s duties include raising funds from alumni who include one Rupert Murdoch.

Such encounters might have been ideal preparation for the storms gathering around his new book, Ted Hughes: The Unauthorised Life, which has just been longlisted for the Samuel Johnson Prize. The book was five years in the writing - and Bate was even gathering material during his investiture by Prince William last May. “I had heard that Ted Hughes used to read bedtime stories to him and his brother. He corroborated this, and told me of poetry evenings with the Laureate and how his father keeps a private shrine to Ted at Highgrove. Hughes really was a kind of shaman, held in enormous affection and esteem by all the royal family.”

Bate himself was drawn to Hughes “not just because of the poetry, but because of his work on Shakespeare, the classics, environmental activity, Coleridge, mental health. All the things so much of my own work has been about. This was the book I was born to write.” Nevertheless, he accepts that his original desire to trace the evolution of Hughes’ prodigious literary output will doubtless be overshadowed by the poet’s seven-year relationship with Sylvia Plath, which ended on 11 February 1963 when she committed suicide while the couple’s two children slept down the hall.

Hughes’ part in Plath’s heart-breaking death has been the subject of ferocious, often toxic debate, litigation and polemical poetry: “I accuse/Ted Hughes/ of…the murder of Sylvia Plath”, Robin Morgan wrote infamously in 1970. During the 1980s and 90s, Plath’s tombstone was regularly defaced, with Hughes’ name continually erased and replaced. Bate knows that in narrating Hughes’ side of the story he might incur the wrath of those who indict the poet for Plath’s suicide. “I will become a proxy for the anger that some women still feel towards Hughes. But, I do think that the job of the biographer is to tell the story in as truthful and full a way as possible, and not to pass judgement.” Counter-balancing this desire to tell “the whole truth” are ethical concerns that means he has withheld “six really significant facts in order to protect people’s privacy. And I will say nothing.”

Bate was tutored in the treacherous waters surrounding Hughes during a fraught writing process. The Hughes Estate, under the auspices of the poet’s widow Carol, initially gave their blessing to a proposed “literary life”. This project, which Bate calls “Ted without Sylvia”, suited his critical instincts and allowed him to skirt the familiar contentiousness of the Hughes-Plath marriage. “Surely the Plath story has been told fully over and over again? Let’s focus more on his children’s writing, his radio plays, his environmental activism.”

Early in 2014, however, the Estate withdrew co-operation and permission to quote from the poet’s private papers. Bate’s failure to present work-in-progress was the reason given, a charge he accepts and explains. “I don’t show half-baked work to anybody. I don’t show half-baked work to Paula,” he adds referring to his wife, the writer and Jane Austen biographer Paula Byrne.

Bate’s book contract with Faber & Faber was cancelled. He hypothesises that Carol Hughes suspected, correctly as it eventually turned out, that the book’s emphasis was changing. “The Chinese Wall between a literary life and biography was crumbling.” Such a shift was, he insists, not planned or opportunistic, but inevitable. “Ted kept everything. All those journals, all those drafts, all those letters. You don’t keep all that, flog one lot to an American library, and keep a second archive that your widow can flog, without the intention of it being written about.”

Four years of archival research convinced him that Hughes’ work was indivisible from his life, nowhere more so than in his relationship with Plath, who haunted his imagination for 40 years. “She was everywhere. She was all over his dream life, all over his journal writing. He was writing Birthday Letters [Hughes’ final poetry volume about Plath] for 30 years. I do think he loved her till the day he died. She is irreplaceable, the central part of his story.”

Revelations that Hughes was sleeping with another girlfriend, Susan Alliston, on the night Plath took her life have already made headlines. Yet Bate exonerates Hughes of the grave accusation of abandoning Plath completely. “The assumption that Hughes deserted her in this cold London flat is simply not true. You can see from his diary that he visits her every day in that last week. One day they talk about getting back together and moving back to Yorkshire. The next day he goes back and she says, ‘You must leave the country.’ That was her illness speaking. That is what bi-polar is like, that volatility.”

Bate speaks from personal experience. His mother suffered severe depression. “I thought I had been led to write about John Clare because of my interest in literature and the environment. But I suddenly realised that I was addressing my mother’s depression, which I had in many ways tried to block.” Bate’s mother was treated with Lithium, which helped her illness at the cost of “a deadening of the sensibilities”. What might have happened, I ask, if Clare and Plath had been similarly treated? “There is no doubt that those very great *itals Ariel end itals* poems were written at this time of severe mental illness and anger. If that was moderated with a drug regime, she might well have lived – God, if only she had – but we probably wouldn’t have had the poems.”

One could see the uneasy genesis of the Hughes biography as characteristic of Bate’s longer tight-rope walk between academia and populism: his works of scholarly criticism and editing are supplemented by a West End play (a Shakespearean one-man show that he wrote for Simon Callow), a novel and broadcasting. He has grown used to accusations of dumbing down. Bate recalls hearing gossip explaining a failed attempt to win an Oxford Chair: “Bate’s best work is past him. He is wasting his time selling his soul to Sunday newspapers and London publishers.”

Today, he argues for a nobler mission to “make literature, the arts and the Humanities accessible and alive to a wide audience”. The Hughes biography and accompanying BBC documentary, to be broadcast later this year, are attempts to inspire fresh interest in the poet’s work. “What is really scary is that your average, very well-educated young person has not only not read Ted Hughes, but has never heard of Ted Hughes.”

Bate attributes this decline, in part, to a digital culture that elevates fast-moving visual images over text. “It’s an attention-span thing. I see it with my own children.” Bate mentions showing classic movies to his film-obsessed 17-year-old son. “A lot of them, he says, should have been edited. The way his brain works is fast intercutting. Stuff that is old can seem slow.”

Nevertheless, the focus demanded by poetry can be a virtue. Bate and his wife, the writer and Jane Austen biographer Paula Byrne, have edited an anthology, Stressed Unstressed, that uses poetry to encourage mindfulness. “Because poetry is language in concentrated form, you have to concentrate on it.”

Convincing school students and their parents of poetry’s advantages is, Bate acknowledges, a major challenge. He notes that children from ambitious ethnic families tend to apply to the sciences in the belief of a guaranteed job. “The argument to read English or History is hard to wash with parents. Why should my daughter take on a debt of £30,000 to read a bunch of old poetry? How is that going to help her to get a job in this incredibly fierce workplace environment?”

So, why should they read English? Bate cites conversations with Worcester College alumni such as Sir Lindsay Owen-Jones, CEO of L’Oréal, or Stewart Gulliver of HSBC. “What [they] want is not people trained in a particular field of endeavour, but people who are hungry to learn, who can absorb huge amounts of information quickly, who can construct a good argument both verbally and on paper, are prepared to think on their feet and are prepared to be challenged and change their minds. To me, that is exactly what a good Humanities degree is like.”

His advocacy of university per se employs similar arguments. “What was the making of [people like Owen-Jones and Gulliver] was that experience of three years away from the pressures of the instrumental. Three years of thinking, talking, reading, writing and arguing. That is what developed their minds. That is why a university education remains the best possible investment for any young person. To be in this safe space and think the unthinkable, to have teachers with preposterous suggestions. You learn as much from your friends and contemporaries. That is what is irreplaceable.”

The mention of “investment” prompts me to ask about Jeremy Corbyn’s plan to abolish tuition fees. His concern, should fees be rescinded, is how the shortfall could be met fairly. “There is plenty of evidence that a good degree brings a premium in your career. Why should the refuse collector and dinner lady subsidise out of general taxation the cost of training the barrister and the surgeon?”

Turning students into consumers has positives and negatives. On the plus side, “They work a lot harder than we did. They have high standards in getting feedback. Where it’s bad is partly because they are a generation who have been tested to the nth degree since the age of eight, many students are very focused on getting the right answer. They are, perhaps, not prepared to take the risk, to slightly mess about.”

Bate is encouraged by rising university applications, but worries about sharp falls in part-time and mature students. “A really visionary politician would think more holistically about post-16 education. The Cinderella of the education world is actually Further Education, which is incredibly important and just gets forgotten about.”

What, I ask, is Bate’s own “irreplaceable” memory of university? He recalls his one meeting with Hughes, in 1978, when Bate was an undergraduate at Cambridge. Hughes was reading poems from Crow, an event Bate thought would impress a girl. “I hoped a little of the magic would rub off. Hughes looked at me, then at her, and winked. He quietly said, ‘Good luck.’” I wonder if the poet wouldn’t repeat those same words to Bate today.

Ted Hughes: The Unauthorised Biography is published by William Collins, priced £30

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments