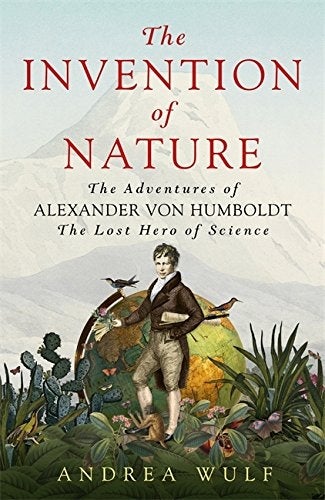

The Invention of Nature: The adventures of Alexander Von Humboldt, by Andrea Wulf - book review

The dizzy heights of an unlikely celebrity

In her new biography of Alexander von Humboldt, Andrea Wulf recounts the exploratory trip he took to Southern Russia in his late fifties in the year 1829. Humboldt was dressed in his daily uniform – a frock coat, a white necktie and a round hat, a kit in which he felt he could meet both kings and students alike – all while on his way up the Altai mountains.

He did not reach the peak, hampered by too much snow. Nearly 30 years previously Humboldt, a well-born German seized by wanderlust inspired by Captain James Cook, tried the ascent of the Chimbarozo, in modern day Ecuador. His attire is not noted for this adventure. He climbed to more than 19,000ft, the highest any man had done, crawling across ridges on which a mountain goat would be nervous, and all the while taking assiduous notes of the flora and carrying a cyanometer to measure of the blueness of the sky. At 1,000ft shy of the summit, an impassable crevasse opened up before him and he conceded that he had to turn back.

Reaching the peak didn’t matter: his reputation was made. He returned from South America to develop a radical new way of thinking about the world. Unlike the rationalist who had gone before him, dividing the natural world into Linnaean compartments, Humboldt observed the continuities; how certain flowers only appear at certain altitudes, how rock formations yield particular results, how magnetism differs with altitude. From these he derived isotherms and a the theory of variation in climate, and applied them globally. He was also the first Westerner to bring back the surprising news that the two great rivers of South America, the Orinoco and the Amazon, were connected. The unusual cold currents to the west of Chile were named after him (many things were, including the penguins) and it was Humboldt who casually observed to his hosts in Russia that the Ural mountains probably contained diamonds.

Wulf’s telling of his life reads like a Who’s Who of his age. Goethe was in his social circle, he inspired Simon Bolivar to seize back his homeland, later Bolivia, from Spanish rule, he befriended Thomas Jefferson and met a young Isambard Kingdom Brunel. He was feted across the US and Europe, whose political tumults are the backdrop to the book. His writings, in particular the Personal Narrative from his South America trip, became a bible for students of nature, among them Darwin, who would later write nervously to Humboldt asking for an audience. Cosmos, a series of volumes published in his seventies and eighties, was the unifying theory of a whole earth system.

If anything, Wulf underestimates her readers’ interest in the detail of the sciences that would inspire a generation of environmentalists through the 19th century and beyond. But in its mission to rescue Humboldt’s reputation from the crevasse he and many other German writers and scientists fell into after the Second World War, it succeeds.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments