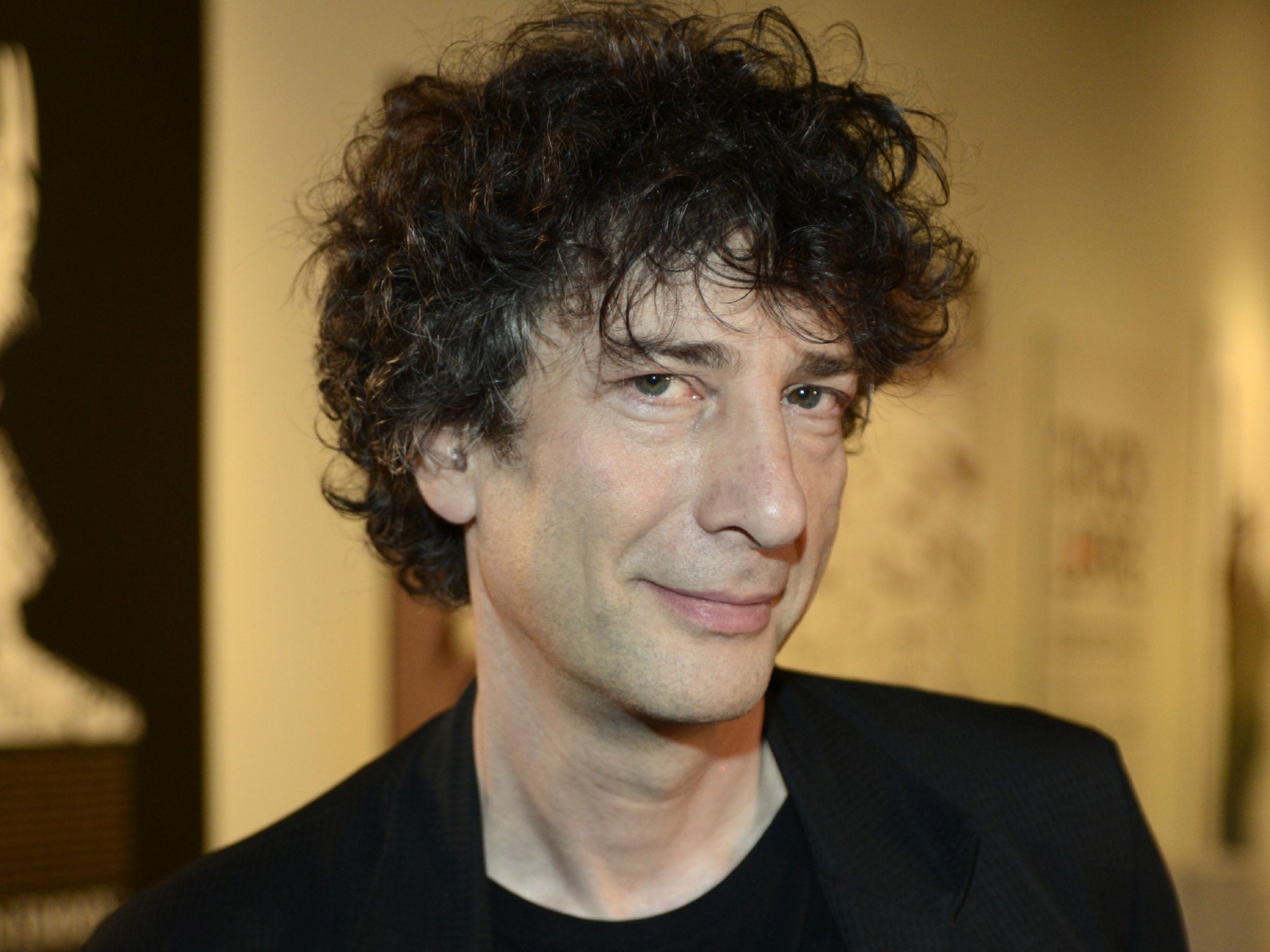

Trigger Warning by Neil Gaiman, book review: Challenging the reader with a world in which the shadow is more dangerous than the sword

Gaiman masters fear like no other writer, tuning into what terrified us as children, the nightmares we used to have, and causing a few too

“Are fictions safe places?” Neil Gaiman wonders in his introduction to Trigger Warning. “Should they be safe places?” The popularity of Gaiman’s writing can be attributed to many things. His skill as a storyteller, infinite imagination, experiments with multimedia, and the ability to envisage new paths for characters that seemed trapped in their old tales all mark him out as an extraordinary talent.

Yet it is Gaiman’s fearlessness that is resplendent in this latest collection. Unafraid to experiment with form or to tamper with fairy tales that most would be comfortable to leave as they are, he gives us characters who are would-be heroes: teenage girls, dangerous princesses, tinkers, dwarves, queens, lonely men ... His is the kind of world in which Red Riding Hood is the one with the teeth.

Short stories have been enjoying something of a renaissance in recent years. Authors such as Gaiman – who published his first short story in 1984 – are already well-acquainted with them, but it seems that publishers have also noticed their readers’ hunger for tales that can be devoured quickly – a five-page piece that can be enjoyed on the train or with a coffee.

In a section of the introduction marked “General Apology” Gaiman says that he believes short story collections “should be the same sort of thing all the way through ... They should not, hodgepodge and willy-nilly, assemble stories that were obviously not intended to sit between the same covers. They should not, in short, contain horror and ghost stories, science fictions and fairy tales, fabulism and poetry, all in the same place. This collection fails this test.”

It is preferable to dive straight into the tales and then meander back to Gaiman’s own take on them in the introduction, where he dedicates a paragraph, or even a few pages, to the background of each tale, or his feelings about a particular character.

Gaiman rewrites conventional imagery to create landscapes that are intended to unsettle. The ground appears to move beneath a character’s feet, worlds are swallowed by darkness or else turn into new ones. In “The Truth is a Cave in the Black Mountains …” the allusions to Celtic myth, including the journey made by the two men, are frequent, yet bring in additional elements of the neo-Gothic: the wolfish look of Calum McInnes and the echoes of screams that follow the narrator wherever he goes.

Vivid imagery is plentiful, and often shocking. But Gaiman made it clear from the beginning that in these tales are death and pain, violence, cruelty. “I saw it in my mind’s eye,” the narrator says. “Her skeleton picked clean of clothes, picked clean of flesh, as naked and white as anyone would ever be, hanging like a child’s puppet against the thornbush, tied to a branch above it by its red-golden hair.”

One or two tales are experiments that have their own quirks and intrigue, but perhaps lack the same flair as their neighbours. “Orange” is written up like the transcript of an interview, and as much as this collection is a mish-mash of horror and poetry, science fiction and fairy tales, it is the only one that doesn’t quite fit.

“Feminine Endings” is a love letter, and so the experience of reading it feels almost like an intrusion – so intimate is the tone of Gaiman’s writing. “I close my eyes and I can see you smiling,” he writes. “I close my eyes and I see you striding across the town square in a clatter of pigeons. The women of this country do not stride. They move diffidently, unless they are dancers. And when you sleep your eyelashes flutter. The way your cheek touches the pillow. The way you dream.”

These same intimacies, paying homage to the strength and beauty of Gaiman’s female characters, are seen in “The Sleeper” and “The Spindle”, in which the women don’t sit around waiting for a handsome prince. They can just as easily be evil as good.

Gaiman challenges the reader with a world in which the shadow is more dangerous than the sword. His language is stark and honest, brutal even, recalling the original Grimm Tales that are exhilarating and frightening and entertaining all at the same time. He masters fear like no other writer, tuning into what terrified us as children, the nightmares we used to have. And causing a few too ...

For instance, at least one of his readers had recurring nightmares as a child about an enormous tentacle that would slip out of the fireplace and drag her into the darkness... Gaiman warns of such a tentacle in his introduction to Trigger Warning, but I went ahead and read it anyway, and enjoyed it immensely.

As he writes clearly at the beginning: “Enter at your own risk.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments