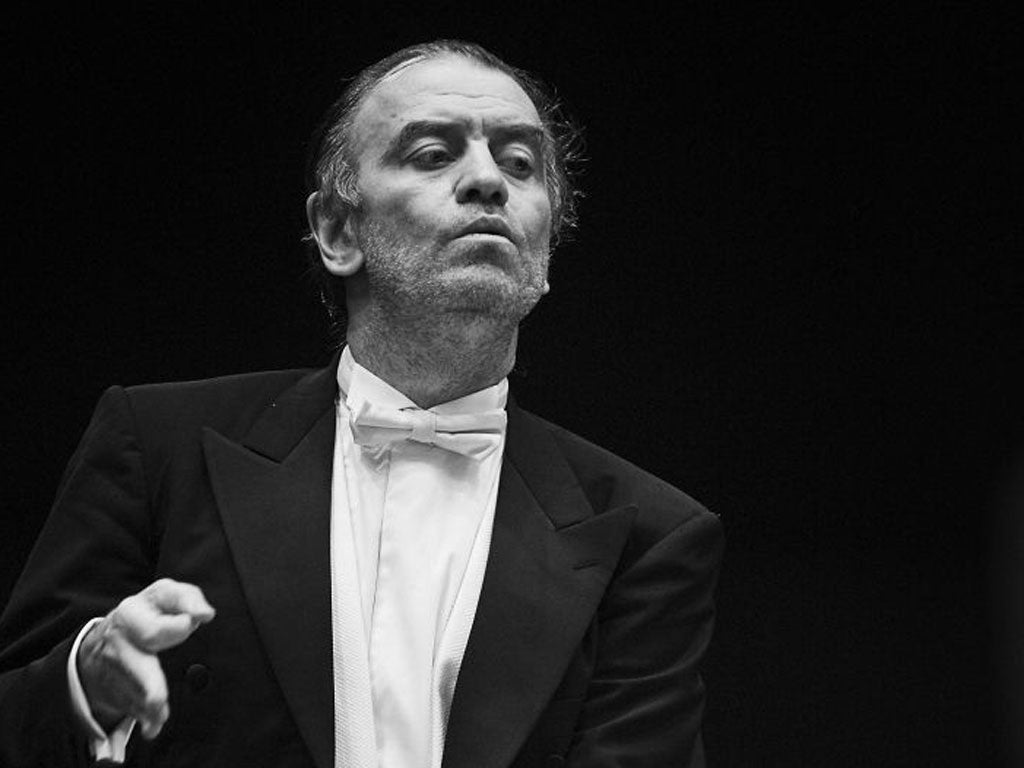

Valery Gergiev: Power player

The maestro tells Andrew Stewart about his passion for Slavic culture – and Putin

It takes less than a minute to rattle Valery Gergiev. He looks irritated while I mention the names of several younger Russian musicians whose careers are located firmly in the West, Vladimir Jurowski and Vasily Petrenko among them. The 59-year-old's roots are securely fixed in home soil, immersed in the affairs of St Petersburg's Mariinsky Theatre and its development as a standard bearer for the best of his country. The suggestion that Russia has no other world-class platforms for her finest classical musicians plays badly with Gergiev. "I think the West does not understand what is good about Russia," he responds. "The West is under the impression that because there are bad things in Russia, it is very bad altogether. I'm sorry to speak like this, but this is where the very big miscalculation occurs."

Gergiev is fiercely proud of the Mariinsky's commanding position in the new Russia and of his part in securing it. He persuaded Boris Yeltsin to invest in raising the venerable St Petersburg institution's global game. In return, the president handed overall control of the Mariinsky Theatre to Gergiev, adding the role of general director to his responsibilities as chief conductor and artistic director. His elevation occurred while Russia's hopes for demokratiya (democracy), were being stifled by the hard realities of dermokratiya – the "shitocracy" of gangster capitalism, political extremism and an economy in freefall. Gergiev recalls feeling optimistic when he took charge of the Mariinsky in 1996, and the pain of Russia's international humiliation two years later, when the rouble became worthless and army recruits begged on the streets of Moscow.

Was he ever tempted to join the exodus of Russia's intelligentsia? "It never occurred to me to leave the country where I was born," he replies. "I was elected as artistic director by the then Kirov family of artists in 1988. The word was that maybe I could do something about the worsening circumstances for everyone in the collapsing years of the Soviet Union."

While democracy handed Gergiev artistic control of the Mariinsky, his subsequent success there owes much to his acute reading of where power lies. "Today, people speak of me being in easy contact with ministers and corporate leaders. Mr Putin is mentioned often – I would say too often!" It would be negligent not to mention Vladimir Putin, given the prominent public endorsement he received from Gergiev during Russia's recent presidential election campaign. Putin appeals to Gergiev. "The choice for me was easy and clear," he explains. "No one is prepared to lead Russia right now the way Mr Putin can."

Isn't that the paradox of contemporary Russian politics today: a strong leader at the head of a weak state, where the rule of law is skewed in favour of those at the top? "When Putin was prime minister in 1999, half the country was sure that Russia would disintegrate. In Russia, you expect many wars. The country was about to disintegrate. Mr Putin stopped it."

Since his re-election in March, Putin has worked overtime putting a stop to things. The trial in Moscow of members of the feminist punk-rock band Pussy Riot confirms that freedom of artistic expression is on the president's hit-list. They were arrested for singing an anti-Putin song before the high altar of Moscow's main cathedral, blasphemy in the eyes of the unforgiving Russian Orthodox Church and a political outrage in the eyes of the Kremlin. The Pussy-Riot-three face up to seven years in jail, if convicted.

Gergiev's analysis of contemporary Russia contrasts the weakness of the country's past leaders with Putin's authority. It also draws on his own Caucasus upbringing. The region, subdued by Stalin's mass deportations and ethnic cleansing, has experienced the conductor's vision of chaos in bloody practice since the collapse of the old Soviet Union. "We do not want to see another war in the Caucasus. Believe me, there is the potential in every village for bloodshed."

He goes on: "As an artist, I don't see harmony in Russia. But I don't see harmony in America, either. I don't see harmony between East and West … or North and South." He has little time for separatist movements within Russia's borders and holds a disarming nostalgia for the idea of Slavic unity, citing the strong ties that bind Russians to the peoples of Belarus, Ukraine and Poland: "Culturally speaking, we are still the same conglomerate," he says. "I think we are somehow close to each other."

The music of Karol Szymanowski is the latest focus for Gergiev's exploration of Slavic culture. He is set to conduct the London Symphony Orchestra in performances of the composer's four symphonies and two violin concertos, presented alongside the symphonies of Brahms at the Edinburgh International Festival from 16 to 19 August. Szymanowski, born in 1882, propelled modern Polish music into the international limelight. The LSO's Szymanowski Project, supported by Poland's Adam Mickiewicz Institute but notably lacking in Polish soloists, arrives at the Barbican Centre in September and will surface there throughout the 2012/13 season, ending next March with the pairing of Szymanowski's Stabat Mater and Brahms's German Requiem. Further outings are planned for the symphonies in Paris, Luxembourg and Frankfurt. "I am blessed with the tremendous comfort I have now to work with the LSO and the Mariinsky [orchestra]. This is where I find more harmony, standing in front of these orchestras."

Szymanowski's Russian connections matter to Gergiev. The composer's family belonged to the Polish landed gentry in the Ukraine, part of the Russian empire. Szymanowski rejected the influence on his work of contemporary German music after absorbing the rich sounds of Scriabin and discovering Stravinsky's early Diaghilev ballets; he later praised Stravinsky as the greatest living composer. "Szymanowski lived in Russia," notes Gergiev. The line sounds strikingly at odds with the composer's prominent role in the Young Poland movement and enduring status as the "father of modern Polish music"; but it reflects Gergiev's conviction that Russia and Poland are linked by their common history and culture: "We are the same people."

Gergiev acknowledges the "tragedy of Stalinist repressions" in Poland, before I remind him of eastern Poland's long subjugation under the tsars, the carnage of the Polish-Soviet War and recent tensions after the plane crash near Smolensk that destroyed Poland's political elite. "I'm thinking of these events philosophically today," he says. "Don't you think Russia and Poland have issues? Of course they have issues!" The LSO's Szymanowski Project, he says, flows naturally from the bridge-building of the Mariinsky's acclaimed performances of the composer's opera King Roger, four years ago in St Petersburg – its Russian premiere – and in Edinburgh. "Let's hope this will be an even bigger statement about how Szymanowski's music does not have borders."

Gergiev/LSO: Usher Hall, Edinburgh, 16-19 Aug (eif.co.uk); Prom 52, 22 Aug (royalalberthall.com); Brahms and Szymanowski, Sep-Dec (barbican.org.uk)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks