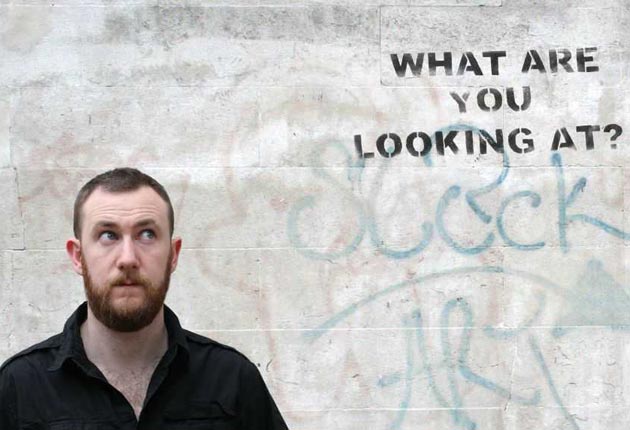

Alex Horne - How to invent a word

How hard can it be to break into the dictionary? Comedian Alex Horne recounts his long journey to linguistic immortality

For some people, four years spent striving to get a word in the dictionary might represent a hefty lump of time wasted. But from the moment I decided that I'd try to break a word into the language, my endeavour has made complete and utter sense to me. In fact, as I've edged ever closer to lexical immortality, the ambition has felt not just reasonable, but honourable.

I have always been a wordy sort, revelling in crosswords, Countdown and puns from an unnaturally young age. I now write books and jokes for a living but the idea of creating a single word has long seemed to me the most refined of all writing tasks. Just thinking about having my own word in the Oxford English Dictionary gets me giddy. A verbal invention would represent the ultimate achievement, the finest legacy to leave my progeny. It's exciting enough to have people look up a book of yours in the library but to look up a word of mine in the dictionary would, I think, be the most worthy of all claims to fame.

So, on 7 December 2005, taking a convenient chronological landmark as my stimulus, I sent the following message to 10 of my friends:

Today, I am 9,950 days old. On January 25th 2006, I will celebrate my 10,000th day on earth and would like you to help me mark the occasion by participating in a project provisionally entitled Verbal Gardening.

On my tkday (the official name for such a birthday), I am going to scatter a handful of verbal seeds into the language. These will be new, original, freshly coined words or phrases which, over the next 1,000 days, I am going to water and watch to see if they can flower and thrive.

But for these words to flourish, I need assistance both in the embedding of the seeds and the monitoring of any future growth. That's where you come in. You nearly all work in the field of communication. You are all trustworthy and innovative. And you all have a twinkle in your eye. You may be a director or an actor, a poet or a teacher, a nightclub promoter or a health and safety expert, but besides your chosen profession you also possess skills that can help me achieve me dream.

So are you in?

Thankfully, they all were, and with their invaluable input, I set about inventing words that I thought stood a genuine chance of survival, not wacky or particularly funny creations, but practical items that might just endure in the cut-throat world of words.

We decided, for instance, to introduce "honk", meaning money or cash, to the language. Of course, we didn't invent the sound or spelling of "honk". It was actually a goose who said it first before some anonymous human borrowed the cry to describe the noise of his new-fangled car horn. But thanks to our Verbal Gardening project, "honk" is now used in a financial context by a steadily increasing number of people. "I haven't got any honk on me," a shopper might be heard to exclaim, "I'll have to go to a honk machine".

There was considerable thought behind the launch of "honk"; money has always been a fertile field for slang and "honk" is punchy and memorable without being too obtrusive. Echoing the brashness of "bling" and "wonga", it seemed perfectly suited to a new pecuniary role. With persistence usage, I was confident it could earn itself a new dictionary definition.

You might think hitching a ride on a pre-existing word is cheating but as one of the world's few dedicated neologists, I can assure you it's not. It's just forward planning. Winning a place in the dictionary, which had to be our final objective, is not as straightforward as one might think. You can't just write to the authorities with a new word and its meaning. Instead, dictionary editors require substantial evidence that that word has been used by people from all walks of life for several years before even considering accepting it. So having cooked up "honk" and several other pragmatic new terms we set about compiling proof that they were indeed in constant and prolonged use.

Most eminent etymologists will tell you that such a deliberate quest is a waste of time, a mental safari, a sysiphean pursuit. In his book, Words, Words, Words ("I'm looking for a good time" would have been my chosen subtitle), the respected linguist, academic and author David Crystal writes, "It is rare indeed to find a single individual altering the character of a language's lexicon."

Now, I don't want to argue with someone who has written or edited over 100 books, who was awarded an OBE for services to the English language in 1995 and who has successfully coined his own term, "ludic linguistics", to describe wordplay, my pride and joy, so I won't. I will, however, stick up for the single individual and say that while one person might seldom change the "character" of a lexicon, all language must be affected to some degree by individuals. It is people who use and change languages, people who use words for the first time. And when they do, they don't do so by committee.

If you go back far enough, every single word (with a paddleful of exceptions that might simply be natural human noises, like "mama" and "telly") must have been used first by some single person, to describe something hitherto unrepresented in language. It must be thanks to single individuals that we have the language we now speak.

Take "bootylicious", a striking adjective that recently succeeded in scaling the dictionary walls, thanks to a solitary soul called Beyoncé Knowles. Yes. She did it. Beyoncé got a word in the dictionary. And if Beyoncé could do it, I thought, I could do it (which isn't always a mantra for my life. I don't always compare myself to one third of Destiny's Child. But on this occasion I felt I was justified).

As the American Billboard's Top Female Artist of the Decade, Beyoncé has enjoyed more direct access to the ears and tongues of the world than me. But being a comedian, I have been able to spout my words from countless stages across this country, scrawl them in the guestbooks of every guesthouse I've stayed in, and implant them in ever motorway service station I've passed through. I've also brandished them on banners at major sporting events, branded them onto mugs, T-shirts and umbrellas and casually dropped them into countless local radio phone-ins. I've infiltrated several schools and (mis)educated credulous schoolchildren, I've confused friends, family and many many strangers, I've even managed to infiltrate the holy grail of mass communication, television, infecting such varied shows as Daily Politics, Loose Women and Channel 4's mighty Countdown.

And I'm not finished yet. Until the dictionary bouncers wave each of them through, I will continue collecting evidence that my words are indeed words. If, for instance, I ever get the chance to write an article for a respected national newspaper, I will endeavour to squeeze all of them in somewhere. If even one reader takes a honk and passes it on I'll be happy. So, please make me happy. Remember, this is an honourable pursuit, honest.

© Alex Horne 2010

Alex Horne is currently on tour with Wordwatching, which has also been published as a book by Virgin ( www.alexhorne.com). He appears on 'We Need Answers', Tuesdays, 10pm, BBC4

Destination mirth: Four comedy odysseys

Danny Wallace: Yes Man

Danny Wallace is the king of the comedy quest, having started his own cult and tracked down his old school friends in the name of humour. In 2005, he published the novel 'Yes Man', charting his six-month odyssey to say "yes" where he would previously have said "no". In 2008, 'Yes Man' was made into a Warner Bros. film, starring Jim Carrey.

Dave Gorman: Googlewhack

Danny Wallace's best mate is also a fan of the comedy journey, having travelled the length and breadth of the land looking for men who shared his name. In 2003, he toured Britain with his show about tracking down people who had authored Googlewhacks, a Google search query that consists of two words and provides only one result. The trip led to a nervous breakdown. Last year, he spent 33 days cycling 1,563 miles to the four corners of the UK, stopping off to do a gig each night.

Tom Wrigglesworth: Lena's Law

After an unpleasant (and hungover) encounter with a Virgin Trains conductor on a journey from Manchester to London, gangly stand-up comedian Tom Wrigglesworth embarked on a campaign against the company's ticketing policy. His "Lena's Law", to make train fares fairer has now been taken up by Virgin and he is trying to get 25 other train operators to follow suit. The resulting show, 'Tom Wriggleworth's Open Return Letter to Richard Branson' was nominated for the Edinburgh Comedy Award last summer.

Tony Hawks: Moldovan tennis

Having lugged a fridge around Ireland as the result of a pub bet, Tony Hawks made another wager with friend and fellow comedian Arthur Smith that he could single-handedly take on and beat the whole of the Moldovan football team – at tennis. His book 'Playing the Moldovans at Tennis' became a bestseller. Ben Bohm-Duchen

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks