How a 170-year-old 'Leaf' provoked a hunt for the world’s first photographer

Exclusive: The person who took 'the earliest photograph in the world' was not who experts had previously believed, but a hitherto unknown woman

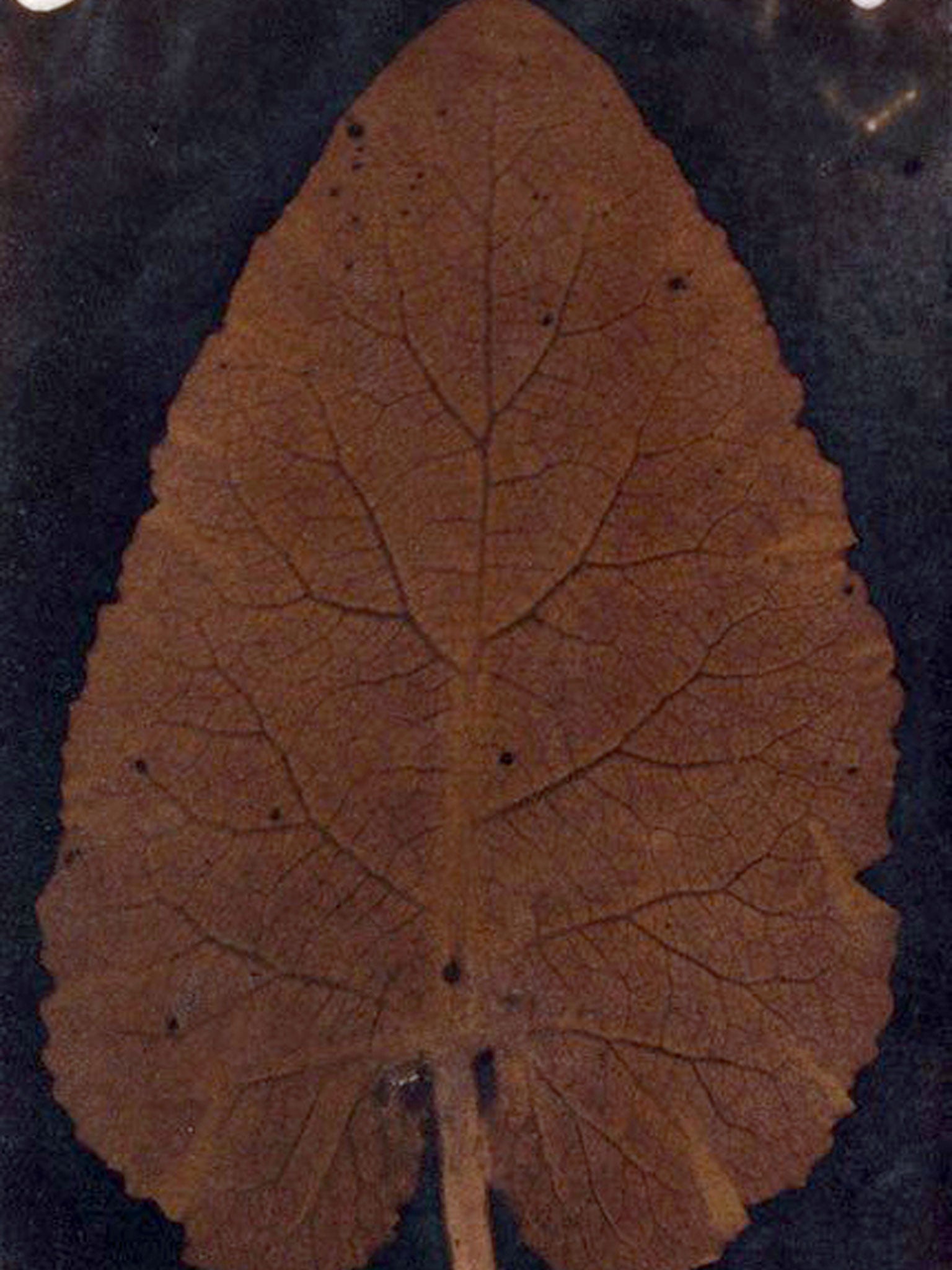

As photographs go, it’s not perhaps the most eye catching. But this image of a humble leaf sparked global headlines – and a media storm – in 2008 when it was suggested that it could be the earliest surviving photograph in the world.

Now the expert behind that claim has come up with another discovery – that the picture was not taken by photography pioneers William Henry Fox Talbot or Thomas Wedgwood, but by a previously unknown woman.

The short essay for an auction house by early photography expert Professor Larry Schaaf led to speculation in 2008 that the 170-year-old image could be worth millions of pounds.

In a talk on Rethinking Early Photography at the University of Lincoln Prof Schaaf, director of the William Henry Fox Talbot Catalogue Raisonné, an online resource of the Bodleian Libraries at the University of Oxford, stressed that his belief it was the oldest image was only a theory.

He described however how the media storm that followed pushed to find the identity of the true author, which led him to a Bristol woman called Sarah Anne Bright, who made the image in 1839.

Revealing his findings and ending the controversy was “a huge relief,” he told The Independent. “It was great to get The Leaf off my back,” he said. The story began with his unpaid essay published in a Sotheby’s catalogue in 2008 on a photogenic drawing – where the leaf was laid directly on photogenic paper – attributed to Fox Talbot (1800-1877) which was brought in for sale.

He wrote that it was not by Fox Talbot, saying the attribution should be changed to “Unknown Photographer” and speculated it could be any number of photographers going back to Wedgwood, the son of potter Josiah who died in 1805. If it was a Wedgwood, that meant it could be one of the oldest photographic images. One auctioneer speculated that “the sky could be the limit” on its price.

Prof Schaaf said his theories were meant to be speculative and was not prepared for what followed. “It was an unpleasant experience and I didn’t like the international exposure. The Leaf got its 15 minutes of fame. It was such a feeding frenzy I wanted to stay back from it.”

The doubts raised meant it was withdrawn from sale. While the media storm died down, Prof Schaaf set out on the trail of clues to discover the identity of the real author.

The Leaf, first sold at Sotheby’s in London in 1984 for £6,000 by the Bright family from Bristol, had been one of seven images in the page of an album which are now split between different owners.

A watermark on another image from the page, revealed by a private collector who came forward in the wake of The Leaf’s media fame, gave Prof Schaaf the clue he needed to locate the photogenic drawing back to Bristol in 1839.

The album was owned by merchant and MP Henry Bright and it became apparent the image had been taken by one of his family, either him or one of his five siblings. After contacting the family in the UK and Australia and viewing the archives in Melbourne, Prof Schaaf attributed the work to Sarah Anne Bright (1793-1866). Inscriptions on The Leaf match the handwriting on her watercolours and other material in the archive, leaving “little doubt” it is Sarah Anne.

While many experiment with photography at the time, “these days we only have a tiny handful of examples, and those like this with a good pedigree and this good condition are very rare,” Prof Schaaf said.

He now hopes to explore Sarah Anne’s story further. “I’m hoping to pump some life into her, that’s the next step,” he said. Her only portrait is a silhouette, a common 19th century portraiture. “It’s symbolic as we just have a shadow of who she was.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments