Mel Brooks: The comic genius and risk-taking director on how retirement is not an option and faking happiness

The versatile Mel Brooks has won every award going but, at nearly 90, he tells Gill Pringle, he’s not done yet as he sets his sights on the London stage

He turns 90 years old next year, but Mel Brooks has no intention of slowing down. Retirement is not an option.

“I’m a lucky man. I’m not working at the post office, I’m not loading a truck, I’m not digging holes in the ground and I’m not homeless, sleeping under a bridge. I’ve got a wonderful life and I appreciate it so why stop now?” says Brooks, who simultaneously shocked and amused movie-goers with his debut movie The Producers in 1967, which featured the memorable musical number “Springtime for Hitler.”

“Nobody wanted to release it because the war was still too fresh in their minds. They thought I was crazy. But we’re grateful to Hitler for providing such comedic material and an honourable income,” he says mischievously when I meet him at his offices in Culver Studios in Los Angeles, where he shows off the bounty of a glittering career.

In 2001 he was the eighth person to become an Egot – the acronym coined to describe the group of high-flying entertainers who have won all four major American entertainment awards: Emmy, Grammy, Oscar and Tony.

His Olivier award and an Evening Standard award are proudly displayed among those baubles, although his best screenplay Oscar for The Producers is notably absent. “People steal Oscars, you know. You’ve got to keep those things hidden,” he says in a loud stage whisper.

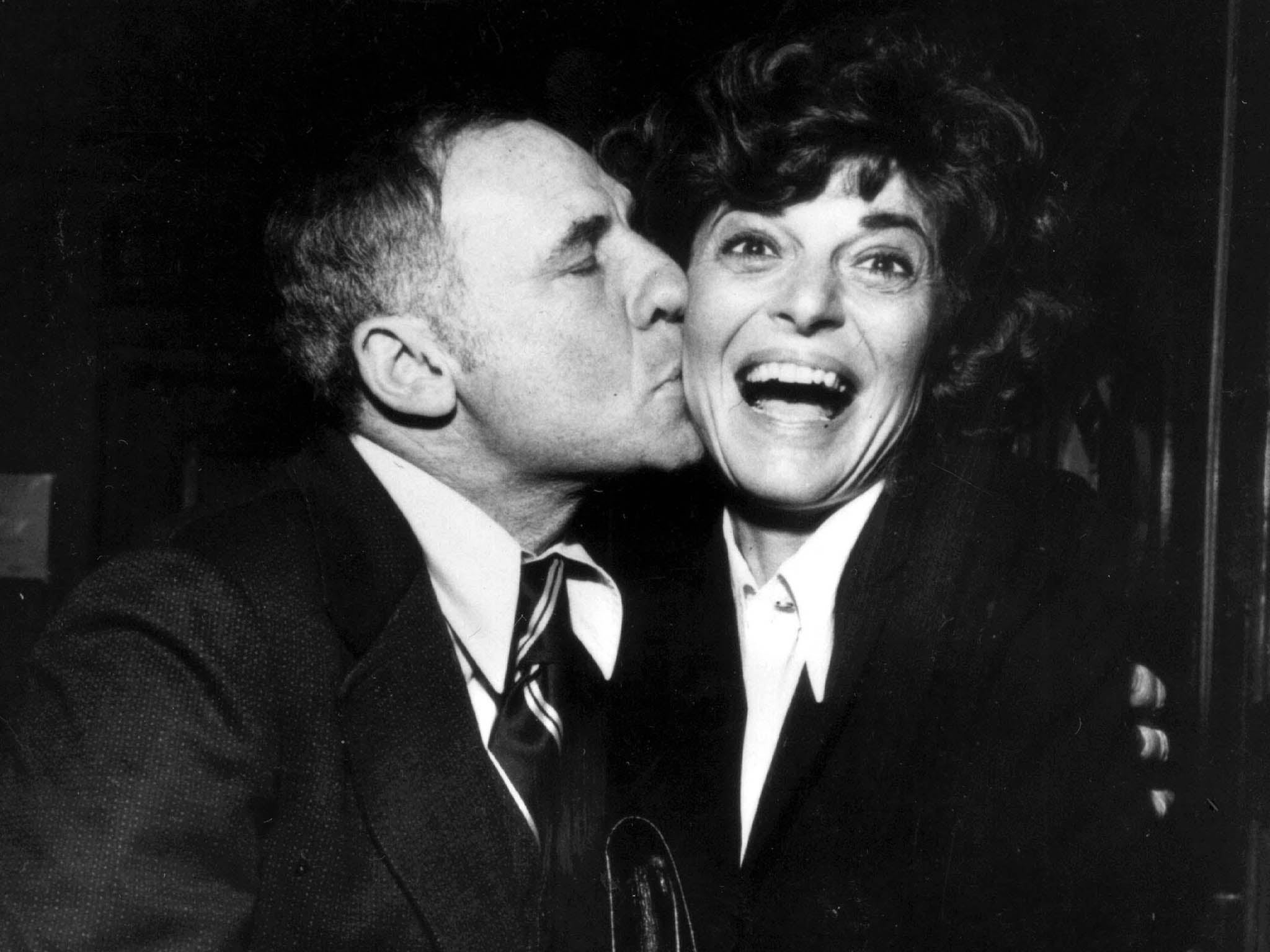

We’re joined by Brooks’s eldest son, Nicholas, 58, from his first marriage, to Florence Baum. “I was eight years old and my dad was then married to Anne [Bancroft] and my mom was remarried,” he recalls. “But dad would still stop by our home in New York every day, and one time he threw down a yellow legal pad on the table and there was the lyrics to ‘Springtime for Hitler’. He told me, ‘I wrote a song today and I want to sing it for you.’ I didn’t know what to think.”

Two years later, the family would travel to Philadelphia for the opening night of The Producers. “It was a big 800-seat theatre, and my stepdad, mom, my brother Eddie and sister Stephanie and myself were the only ones there except for a suspicious-looking guy in a raincoat and a woman surrounded by phalanxes of shopping bags. We kept waiting for the theatre to fill up and it didn’t. It was just us and the bag lady and the raincoat guy, and I said to myself, ‘Well that’s it. We’re sunk’. I was 10,” reminisces Brooks Jnr, a gentle soul who has inherited his father’s love of comedy although he’s too shy to perform, preferring to write and produce, having worked at his father’s Brooksfilms production company for 20 years.

“I was providing some child support and they knew they were finished. They were never gonna get another meal again!” quips Brooks Snr.

On the contrary, The Producers went on to form the backbone of Brooks’s empire, not only establishing him as a comic genius and risk-taking director, but also as a theatrical impresario when the film later became a hit Broadway musical, followed by numerous travelling productions and, 10 years ago, a hit film of the musical.

Among his many achievements, Brooks has directed three of the American Film Institute’s 100 funniest movies: Blazing Saddles (No. 6), The Producers (No. 11) and Young Frankenstein (No. 13). When we meet, he has recently returned from London where he is looking to stage a brand new musical version of Young Frankenstein, the 1974 film which earned a Oscar nomination (for screenplay) for him and Gene Wilder.

“I’m looking for a very specific theatre. I want it to seat between 800 and 1,000 so that when it opens it’s a hot ticket. If you have 3,500 seats, anybody can walk in. I want a theatre where you can’t get in. I’m not looking for money, I’m looking for eyes and I want it to run for a couple of years. People will lose money if it’s under 600 seats. But if it’s 800 seats, people can make a little money and the cast can be paid handsomely and it’s still a hot ticket that can run,” he rasps. “There’s about 15 West End houses between 700 and 1,100, so we’ll find the right one and open in 2016.”

He’s already come up with his dream cast. He’d love Tracey Ullman as Frau Blücher and mentions two British actors for the roles originated on the big screen by Gene Wilder and Marty Feldman, although he calls the next day and asks that we not reveal the cast until the deal is sealed. Young Frankenstein first opened on Broadway in 2007, and toured the US, although the London version will be very different. “I’m rewriting it and cutting out some of the excesses and adding some crazy songs to make it more entertaining,” he says, indicating the black piano in the corner of his office.

He enjoys London almost as much as he does Broadway, fondly remembering his run of The Producers at Drury Lane. “I love London, especially the West End, that conglomeration of 50 or 60 theatres – big ones, little ones, all smashed together. My favourite hotel is the Savoy because if you get a room on the river and you’re in the elbow of it, you can look all the way down past the Houses of Parliament and all the bridges and then look all the way up to St Paul’s.”

He was born Melvin James Kaminsky into a Jewish family in Brooklyn in 1928; his grandparents hailed from Germany and Russia. At 18, he joined the army and was promptly shipped off to Alsace-Lorraine on the French-German border. “I was only there three months and then, on 8 May, the war was over. I was ducking a lot. I didn’t make anyone laugh. I was terrified. There was no laughing.”

Returning home, he began his career as a drummer and pianist, but soon earned a reputation as a stand-up comic which led to him being hired as a comedy writer, alongside Carl Reiner and Neil Simon, on an innovative variety sketch show called Your Show of Shows. Later he would co-create the hit TV spy comedy series Get Smart which, decades later, he helped to reinvent as a big screen comedy starring Anne Hathaway and Steve Carell. He still spends several nights a week with long-time buddy Reiner, both now widowers, watching old movies together.

While much of his career has been based on blatant satire – in movies like Spaceballs, a spoof on Star Wars, or Robin Hood: Men in Tights – his particular brand of Yiddish humour has led to comparisons with Woody Allen over the years, despite their very different styles. “Two Jewish New York screenwriters,” shrugs Brooks, who took Allen under his wing when he joined him as a young writer on Your Show of Shows. “I didn’t know he was going to be a director but he certainly had a great gift for comedy. Our paths have crossed many times since, sharing corned-beef sandwiches and talking about the state of affairs.”

There’s been much joy in his life, although his family gives him the greatest pleasure. His youngest son, Max, 43, his only child with Bancroft, is now a successful writer and author who cut his teeth on Saturday Night Live and penned the screenplay for Brad Pitt’s World War Z.

Now, he hopes, it’s time for his eldest son, Nicholas to shine; his romantic comedy Sam, is due for release in the UK next year. Brooks Sr. is involved and invested as executive producer. The night before we meet, he attended the premiere at AFI in Hollywood, gamely posing for selfies with fans, sporting his trademark baseball cap and goofy grin. He later joined his son and producer Sibyl Santiago on stage, fighting back tears as he told the audience of his pride in his son’s debut film. It’s a gender-bending romantic fantasy with throwbacks to the 30s and 40s, although it’s also pertinent in an era of Caitlyn Jenner, the Jeffrey Tambor-starring TV series Transparent and a plethora of transgender web shows.

“I saw various incarnations of it and I was so against the ending. I said, ‘Are you crazy? No one will accept this ending!’ and then when I saw it last night I realised, it’s the only ending,” says Brooks, who perhaps recognises in his son some of his own bold choices. “Nick’s film is a strange mix of comedy and sweet sadness – and I didn’t give him a single line! Not one.”

“For me, the best comedies are where there’s a few tears mixed with the laughter. I cannot see The Producers without a tear rolling down at the end,” agrees Brooks Jnr. “Especially when Gene Wilder’s Bloom is in the courtroom and talks about Zero Mostel’s Bialystock and says, ‘Life before Bialystock, it was just Bloom.’”

Both men despair at the dearth of decent romantic comedy today. “We have to rely on the Brits for romantic comedy because they’re the only people still making this genre. When Harry Met Sally was the last good American romantic comedy I can remember. Otherwise I look to Mike Newell’s Four Weddings and a Funeral, Peter Chelsom’s Serendipity or Bridget Jones’s Diary. Sam is a homage to those films although most of my references come from yesteryear movies starring Gable and Lombard,” Nicholas says of his low-budget movie which features cameos from Stacy Keach and Morgan Fairchild.

Mel Brooks may have proved his mastery of the slapstick comedy genre, but he also has a passion for romantic drama, and silently produced the Oscar-nominated films Frances, My Favorite Year and The Elephant Man as well as his wife’s Bafta-winning film 84 Charing Cross Road, co-starring Anthony Hopkins.

“I have a lot of baggage and you put that baggage on to the screen and they think The Elephant Man is a ‘schnazola’ comedy, a guy with a big nose, so I kept my name far away from the screen for those films,” he explains.

There’s no secret to his longevity, he insists. “I eat raisin bran and 1% milk every morning but, if I were a cockney kid, I’d say ‘with a little bit of luck’.”

He certainly seems a happy man, despite his enduring sorrow over the death of his wife, Anne Bancroft, from cancer 10 years ago. “I’m faking it, I make-believe it,” he says. “And the audience buys it and we’re all rich.”

'Young Frankenstein’ will open in London’s West End in early 2016

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments