The 2015 Climate change target: 192 nations, two weeks of negotiations – and one world to save

At the end of this year nearly 200 countries will meet in Paris to hammer out an agreement on reducing carbon emissions. Tom Bawden reports on its global aims – and its chance of success

In what is widely regarded as the last chance to save the world from the worst ravages of climate change, 192 nations have pledged to agree a global treaty at a two-week negotiating marathon in Paris at the end of 2015 – setting themselves the most ambitious political task in history.

The plan is for each country to commit to huge cuts in carbon emissions to give the world a reasonable chance of limiting global warming to 2C – beyond which the consequences become increasingly devastating. Last year the fight to curb climate change took some giant steps forward, raising hopes that a meaningful treaty can be agreed, but the task ahead remains huge – some say insurmountable.

What we achieved in 2014

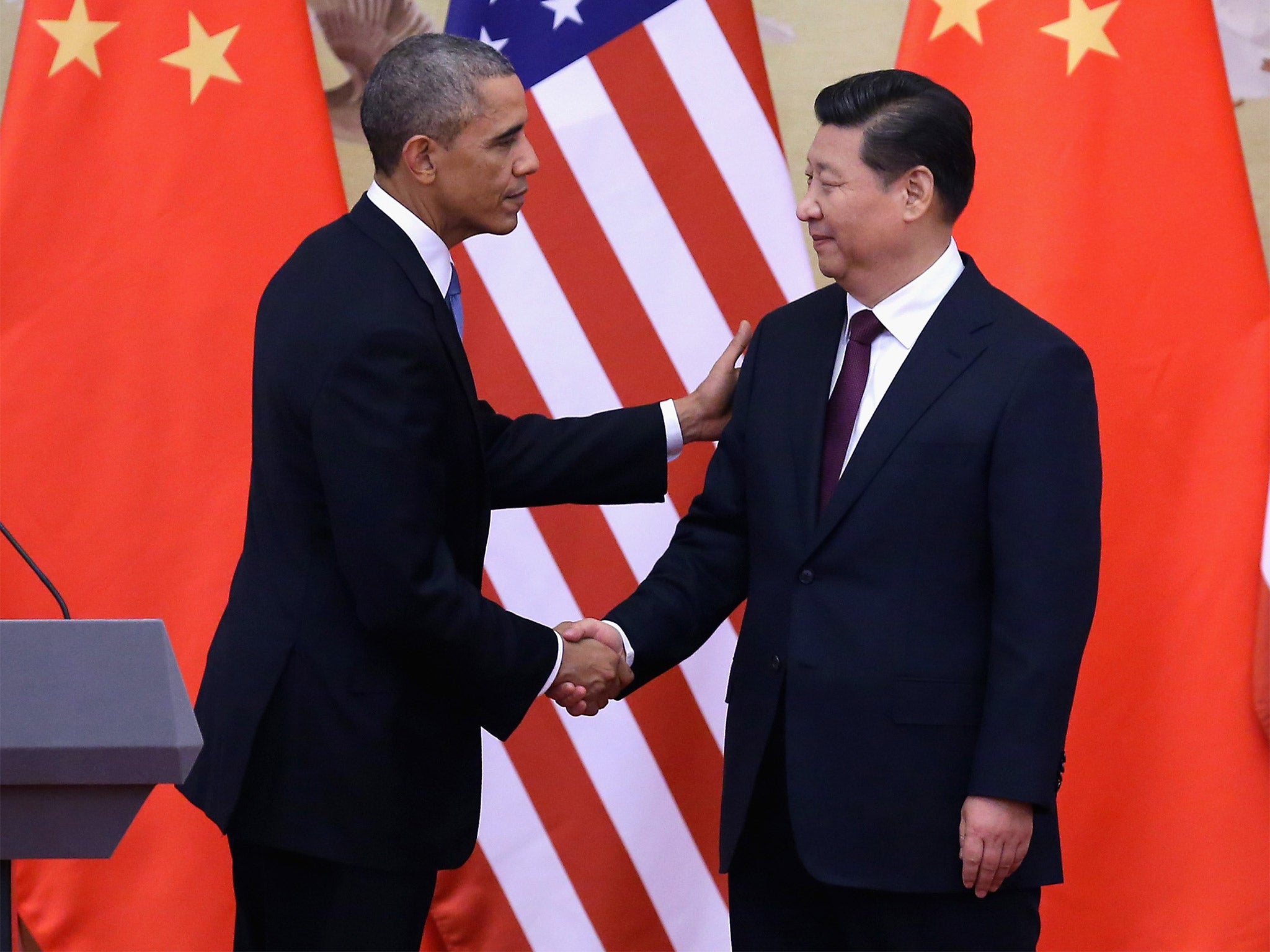

Even the most cynical campaigners conceded we may have entered a new era of climate-change action in November when America and China, the two biggest polluters, made an unprecedented joint pledge to make concrete reductions in their carbon emissions. These countries had traditionally opposed any meaningful activities to tackle global warming, and their decision to sign up to the cause was regarded as game-changing because it meant other countries could no longer hide behind their inaction.

It was all the more exciting because it came hard on the heels of reasonably ambitious EU-wide targets to cut emissions, and a one-off summit in New York at which world leaders agreed to halt deforestation by 2030. The momentum is set to last into the New Year, with India and the US expected to announce some joint initiatives to combat global warming when President Barack Obama visits the country later this month.

The sticking points

Despite the impressive advances last year, the annual UN climate change summit in Lima in December took much of the wind out of negotiators’ sails, reminding them what an enormous task they face. The biggest sticking point continues to be the fierce argument between the developing nations of the world and the richer countries about how the pain should be shared.

The poor countries argue that the wealthy nations put most of the CO2 into the atmosphere so they should do most of the emissions-cutting and give the developing world a chance to catch up. The richer nations accept they have a point, but argue that the developing countries are now producing a huge – and growing – portion of CO2, which we simply can’t afford to put into the atmosphere.

Other sticking points are whether the treaty will be legally binding and whether countries will allow international monitoring of their emissions.

Obstacles beyond the treaty negotiations

Communication remains a big issue. Despite the overwhelming scientific consensus that the climate is warming and that humans are largely responsible, the sceptics are effective at sowing seeds of doubt – aided by the fact that it’s inconvenient having to rein in carbon emissions.

The collapse in the oil price, and associated drop in the gas price that traditionally shadows it, also threatens the green agenda. This is because it makes renewable energy sources such as wind and solar even more expensive by comparison to fossil fuel power, meaning that even bigger subsidies are likely to be needed to attract investment – which will be added to household bills. In short, it’s a tough sell for politicians who are more concerned about getting through the next week than staving off the effects of climate change decades down the line.

What will help the cause?

The weather has played a large role in softening the public’s appetite to make the considerable lifestyle sacrifices that are likely to result from drastic emissions cuts. This development has been underlined by the unprecedented series of co-ordinated marches on climate-change action in November, involving thousands of rallies in more than 150 countries.

In the UK, the worst floods since 1953 last year acted as a wake-up call, while 2014 is looking to have been the warmest on record across the world.

Climate scientists are also upping their communications game. There has been a growing acceptance in the past year or two that there is more to persuasion than graphs and numbers. This has resulted in, among other things, scientists engaging with the public through the arts, for example through plays and poetry. They are also challenging climate sceptic comments more robustly.

Business is playing a part, too. The movement among pension funds to divest of investments in fossil fuel companies has mushroomed from virtually nothing 18 months ago to hundreds of institutions, managing tens of billions of dollars of assets. Developments in renewable technology such as solar and onshore wind are significantly reducing their costs, making them more competitive with fossil fuels and helping to offset the effects of the falling oil and gas prices.

What would happen if a treaty was agreed to limit global warming to 2C?

With the world on course to record a temperature increase of about 5C by the end of this century compared to pre-industrial levels, a successful treaty would change things overnight. Initially, most of those changes wouldn’t be noticeable on the street. Rather, they would involve a rapid change in the collective mindset. But share prices among the fossil fuel companies could begin crashing, as their reserves would need to stay in the ground and so become virtually worthless.

An agreement would also set in motion a bout of feverish entrepreneurial activity, involving the kind of research intensity usually reserved for world wars. This would need to translate very quickly in most parts of the world to a complete overhaul of the transport and energy network. By 2050, electric vehicles would become the norm and large trucks would switch to gas. Coal and gas would be quickly phased out, with wind, solar and nuclear taking up most of the slack, and any remaining fossil fuel stations would need to be fitted with technology that sucked emissions out of the sky. This technology has yet to be proven commercially viable on a large scale.

Virtually every building would adopt low-power LEDs for lighting. Flying would become extraordinarily expensive, the cost of meat would soar and virtually everything would be made from recycled material.

More excitingly, there would certainly be all sorts of shifts in behaviour that we can’t even imagine at the moment – some of which would fail dismally while others will prove revolutionary.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks