The Big Question: How good is English wine, and will we ever be a major producer?

Why are we asking this now?

English wines have won a record 24 medals at the world's biggest wine competition, the International Wine Challenge in London. A Cornish wine, Camel Valley Bacchus, was awarded a Gold Medal.

So is English wine getting better?

Yes. Oenophiles say that after decades of trying, English winemakers have finally matched grape production to our climate. English sparkling wines are particularly celebrated, and can rival – if not outdo – the cheaper Champagnes. In 2005, English wines won 10 medals at the International Wine Challenge, rising in successive years to 16, 21, 22 and, now, 24.

Why are we asking this now?

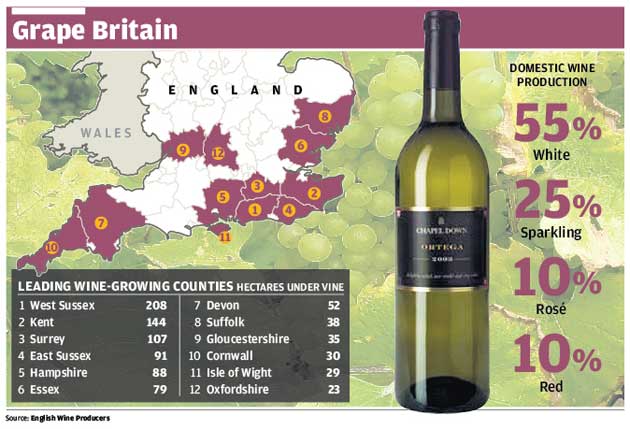

Most vineyards are in the south-facing, chalky hills of the South, stretching from Cornwall and Devon in the West Country, across to Hampshire, Sussex, Surrey and Kent in the South-east and up to Suffolk, Cambridgeshire and Essex in East Anglia. Grapes are grown as far north as Leventhorpe in Leeds, which is the most northerly commercial vineyard. The six most celebrated English vineyards are Camel Valley in Cornwall; Three Choirs in Gloucestershire; Nyetimber in West Sussex; Ridgeview in East Sussex; Denbies in Surrey; and Chapel Down in Kent. Last year 1,500 vines were planted at Forty Hall Organic Farm in Enfield, London.

Is there any Welsh, Scottish or Irish wine?

Northern Ireland and Scotland are too chilly to grow grapes. There are 23 Welsh vineyards, though, most of which – 16 – are in South Wales.

When did English wine production begin?

English wine is not new. The Romans planted vines here 1,600 years ago, cultivating them in what is now London and as far north as Lincolnshire. Wine production continued into medieval times. The recent burst of viticulture stems from the 1970s, when enthusiasts began planting vines in large numbers in Kent and Sussex. Money was poured into what was described at the time as an English wine boom. But the vineyards were small and modern English viticulture was in its infancy.

How much of a struggle was it for the industry to get off the ground?

Believing southern England's climate to be so similar to Germany, and mindful of the contemporary popularity of Liebfraumilch and Hock, vineyard owners planted cool Germanic grapes such as Reichensteiner and Bacchus. In fact, southern England's climate is similar to the Champagne region.

"A number of reasons for the gradual fall in the mid-1990s to early 2000s can be attributed to wrong varieties, wrong sites, uncompetitive quality wines and marketing difficulties," says Julia Trustram Eve, of English Wine Producers, the trade body for English vineyards. In the decades since this false dawn, there has been consolidation of wineries and a growing professionalism, which has allowed English wine to perform adequately, and sometimes well in international blind-tastings. But the production peak in 1993 of 1,065 hectares was only exceeded last year.

Who buys English wine?

Wine buffs who enjoy comparing English wine with that from other countries, dinner-party guests who like to surprise their host, and corporate hospitality companies keen to demonstrate their patriotism and innovation. Ministers have been keen to showcase English wine at official functions. At the Downing Street and Excel dinners at the G20 summit in April, the US President Barack Obama and other world leaders were served Nyetimber's award-winning 1998 Blanc de Blancs.

Where can you buy it?

Most major supermarket chains stock English wine, though the range will vary according to the nature of the chain and size and location of the branch. Asda, the Co-op and Sainsbury's do not stock any English wine. Tesco stocks just four across the country, including Chapel Down's Bacchus and Three Choirs' Rich and Fruity. Waitrose has the biggest range, 37.

Online and high-street vintners also stock bottles. The wineries sell their own produce at estate shops. Most of the leading vineyards offer tours which culminate in a tasting. They are an important and stable source of revenue to a seasonal business relying on the weather. Denbies, for instance, is Surrey's leading visitor attraction, pulling in 375,000 people each year.

How does English wine compare to what the Continent has to offer?

Production is small, about 2 million bottles per year, less than 1 per cent of the amount produced in France (6.9 billion bottles) and Spain (5.8 billion). In terms of quality, English whites compares with mid-range wines (£5 to £15 a bottle) from around the world. Particularly celebrated are the sparkling wines which, in a good year and from the best producers, are better than many Champagnes. But English wines are not cheap. Because production is low and demand relatively high from native buyers in a country which drinks 1.4 billion bottles of wine a year, you buy British wines to taste the English countryside, to experience something new, and to support a fledgling industry.

Will we ever become a major wine producer?

There isn't enough land in southern England for the UK to become a major wine producer, at least in the short term. Total production represents only 1 per cent of British wine consumption.

One of the bright spots in the darkening skies of climate change is that rising temperatures in England will make wine production easier. The optimum wine-producing climate may only be around for a few decades though. By 2080, much of southern England, including the Thames Valley and parts of Hampshire, will be too hot to grow vines, according to a study by Richard Selley, emeritus professor at Imperial College's Department of earth Science and Engineering, who based his predictions last year on modelling from the Met Office.

On the upside, by 2080 large areas of England such as Yorkshire and Lancashire will be able to grow red grapes such as merlot and cabernet sauvignon historically grown in the hotter wine regions such as the south of France and Chile, says Professor Selley.

Any tips on the best bottles?

The "crisp, dry, grassy hedgerow" Bacchus often finds favour with English palates and can be found in supermarkets. Waitrose sells the gold medal-winning Camel Valley Bacchus for £17.99, while Ocado has English Wine Group's £9.49 Chapel Down Bacchus. For £21 a bottle or £126 a case, the Wine Society is selling Ridgeview's Merret Fitzrovia Rosé 2006, which Joanna Locke MW (Master of Wine) described as "delightful". If you can get hold of Nyetimber's 1998 Blanc de Blancs – the one served at the G20 summit and which won a 1999 Gold Medal at the Chardonnay du Monde competition in France this year – do, if you can afford it. It costs £140 for six bottles at Ditton Wine Traders online.

Should we really take English wine seriously?

Yes...

* Greater professionalism and expertise have allowed English wine to perform well in blind-tastings.

* Bottles produced in the South of England have beaten foreign competition to win gold and silver medals.

* English wine has its own distinctive crisp, floral taste, redolent of summer evenings and freshly-mown grass.

No...

* English wine is too expensive; you can buy a better foreign wine for less.

* Although England won 24 medals at this week's International Wine Challenge, France won 729, Australia 591 and Italy 405.

* Britain's climate is not yet warm enough to grow grapes to a quality that can match other countries.'

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments