75 years on from rationing, what did we learn?

Brits were healthier as a result (but fish and chips were never rationed, as safeguarding the national dish was a priority for the government)

January is the time of the year when thousands of us pledge to cut down on our food intake for the New Year. But 75 years ago today, 8 January 1940, no one had a choice. Britain had entered the fifth month of World War Two, and food rationing had begun. It would continue for over fourteen long years, far beyond the duration of the war itself.

The country imported two-thirds of its food, all of which had to be shipped over oceans teeming with German U-boats. The Ministry of Food did not want to risk the lives of sailors for food that would be wasted, and reducing imports also saved money for armaments. Surprisingly, 60 per cent of Britons told government pollsters that they wanted rationing to be introduced, with many believing that it would guarantee everyone a fair share of food.

The press reaction was mixed. The Daily Mail launched an all-out attack on William Morrison, the Minister of Food: “Our enemy’s butter ration has just been increased from 3ozs to just under 4ozs,” it wrote. “Perhaps because of Goering’s phrase ‘guns or butter’, but has been given a symbolical significance. But mighty Britain, Mistress of the Seas, heart of a great Empire, proud of her wealth and resources? Her citizens are shortly to get just 4ozs of butter a week.”

Meanwhile, a correspondent in The Times reacted with stoicism: “It is rationing which is very limited in extent and most people will readily agree with the Minister for Food that it can have no untoward effect on either health or efficiency,” he wrote. “Most people eat more than they need (except the unemployed and their dependents and the others of the poor), and, in spite of rationing, many will probably continue to eat too much.”

Other people turned to humour, including one Bernard Denvir, the victor of a poetry competition in The Spectator on 19 January 1940. He wrote a satirical poem entitled, “Doctor John Donne Contemplates the Introduction of Rationing in a Secular Sonnet”. He adopted the voice of the seventeenth-century English poet, known for his vibrant language. Ration tokens were described as “mystik booke-enclosed, emprinted stamps” which “set checks upon our gastronomic fate”.

Every citizen was issued with a booklet, which he took to a registered shopkeeper to receive supplies. At first, only bacon, butter and sugar were rationed. But gradually, the list grew: meat was rationed from 11 March 1940; cooking fats in July 1940, as was tea; while cheese and preserves joined in March and May 1941.

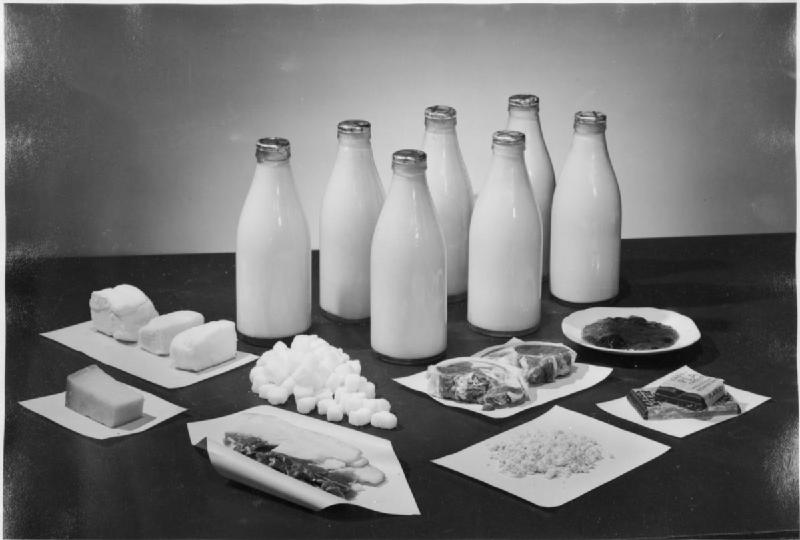

Allowances fluctuated throughout the war, but on average one adult’s weekly ration was 113g bacon and ham (about 4 rashers), one shilling and ten pence worth of meat (about 227g minced beef), 57g butter, 57g cheese, 113g margarine, 113g cooking fat, 3 pints of milk, 227g sugar, 57g tea and 1 egg. Other foods such as canned meat, fish, rice, condensed milk, breakfast cereals, biscuits and vegetables were available but in limited quantities on a points system.

Rationing in Britain was hard – but shortages were far worse elsewhere. Collectively, 20 million people died as a result of malnutrition in the war, compared to 19.5 million in combat. In Ukraine, peasants dug up dead horses to eat their flesh, while in Greece, 2,000 people perished every day from hunger. In Britain, rationing created the best-nourished generation of pregnant women in history, as poor people received enough nutrients to maintain their health.

According to Professor John Ashton, president of the Faculty of Public Health, modern Britons are actually at a greater risk of malnutrition than they were under rationing. He said in an interview with the Sunday Times: “Nobody is arguing for going back to rationing but it is salutary to think that when we had rationing everybody was getting the essential nutrients. What we have now is malnutrition of a different kind than we have ever experienced before, except from the wealthy who used to sometimes suffer from the sin of gluttony, which is a form of malnutrition. We have mass gluttonous malnutrition.” A study by the International Obesity Task Force found that children today consume 3,000 calories per day, which is 1,200 more than their counterparts on rations - the equivalent of eight chocolate bars.

The government urged Britons to grow vegetables, and created special cartoon characters to encourage children to eat healthily, including “Dr Carrot” and “Potato Pete”. It was during the war that the popular myth that carrots made you see in the dark was created, with posters claiming that they would help in the blackout. Allotments were established on any waste ground as part of the “Dig for Victory Campaign”: flowers in public places were replaced with cabbages, and the moat of the Tower of London grubbed up for planting.

But not everyone played by the rules. A large black market developed for food, as noted by The Spectator, on 16 February 1940. “Rationing is one of those cases in which many people otherwise wholly admirable suffer from quite astonishing moral myopia. Everyone understands perfectly well that the Government has introduced rationing for excellent reasons. It should be a point of honour to keep within the ration – which in point of fact is absolutely adequate - and not find means of supplementing it irregularly.”

Wrongdoers, found to be smuggling goods and selling them for inflated prices, were hauled in front of the courts. In June 1941, a gang of seven men, including a company director, a grocer, a salmon curer, and a merchant, came in front of the central criminal court, and were found guilty of stealing. The recorder, Sir Gerald Dodson, criticised the men for their selfishness. “When one considers that sailors are giving their lives daily to preserve what is called the lifeline of the country, it is essential that it should not be thought that if property brought to this country is stolen at the docks that there is a market for it, for it is cutting the lifeline at the shore.”

But, being Britain, fish and chips were never rationed. Professor John Walton, author of Fish and Chips and the British Working Class, told the BBC that safeguarding the national dish was a priority for the government. "The cabinet knew it was vital to keep families on the home front in good heart," he said. "Unlike the German regime that failed to keep its people well fed, and that was one reason why Germany was defeated. Historians can sometimes be a bit snooty about these things but fish and chips played a big part in bringing contentment and staving off disaffection."

After the war had finished, the pain continued. On 27 May 1945, just three weeks after Victory in Europe Day, rations were actually reduced, bacon from 4oz to 3oz and cooking fat from 2oz to just one. So it is of no surprise that when restrictions were lifted on 30 June 1954, when meat stopped being rationed, people reacted with delight. That December, colour returned to the once dull streets of Britain, and shop windows were piled high with sweets. The sheer joy of this moment comes across in a report in The Times, on 20 December.

“The shops display an almost Dickensian abundance of sweets and foods to supplement the turkey and the pudding which are the mainstays of the season’s menu. Besides the usual crop of spaniels, galleons and crinolined ladies, the lids of the biscuit tins sport any number of quasi-artistic designs, from a cross-stitch sampler to a gaudy circus scene.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks