The Big Question: Can Cognitive Behavioural Therapy help people with eating disorders?

Why are we asking this now?

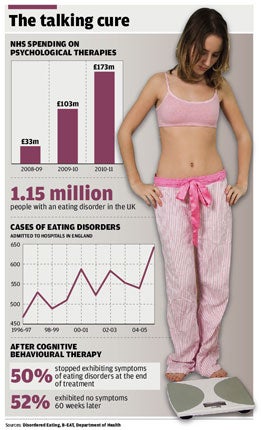

An estimated one million people in Britain suffer from eating disorders which are notoriously difficult to treat. They have the highest death rate of any mental disorder, either from suicide or form the effects of starvation.

Researchers have developed a new form of psychotherapy which they say has the potential to treat more than eight out of ten adults with eating disorders. The therapy is an "enhanced" form of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), which was tested on 154 patients in Oxfordshire and Leicestershire. Two thirds showed a "complete and lasting response", sustained over the following year, and many of the rest showed substantial improvement, according to the researchers from the University of Oxford. The results are published in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

What is cognitive behaviour therapy?

At its simplest, it is a technique for helping people replace habitual negative thinking with positive thinking, by getting them to see the glass as half full not half empty. The aim is to help the individual replace dysfunctional thoughts such as "I knew I would never be able to cope with this job" with alternatives such as, "The job is not going well but I can work out a plan to deal with the problems." Negative thinking is very prevalent in western societies with their emphasis on competition and success. The problem is getting people into treatment.

How does it differ from other forms of therapy?

It is brief, it is direct and it works. It is one of the few therapies for which there is good clinical evidence of its effectiveness. CBT has revolutionised the way doctors approach the treatment of depression. Whereas in the past they might have prescribed Prozac or other antidepressant drugs, CBT is now the treatment of first choice – where it is available.

Instead of focusing on the causes of distress or symptoms, that may lie buried in the past, the therapy examines ways to improve the patient's state of mind now. A course of treatment would usually last for six to eight half hour sessions with a trained counsellor who would offer practical help to the individual to alter ways of thinking to challenge feelings of hopelessness.

Is it popular?

It is, but it is about to become a lot more popular. Earlier this year Alan Johnson, the health secretary, announced an extra 3,600 therapists would be trained to provide the treatment on the NHS at a cost of £173 million a year from 2010. The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE), says CBT should be the first line treatment for mild to moderate depression, followed by drugs only if it proves unsuccessful. At present the demand for the therapy exceeds the supply in most places and waiting lists are up to six months – too long for many who instead resort to antidepressants.

How does it help to avoid eating disorders?

In 2004, a form of CBT developed by Professor Christopher Fairburn, a Wellcome Trust fellow at the University of Oxford, became the first psychotherapy to be recommended as the standard treatment for bulimia nervosa – the bingeing-vomiting eating disorder – by NICE. Bulimia accounts for a third of all cases of eating disorders, which together affect about one million people in Britain. One in ten of these have anorexia and most of the rest, more than half the total, combine features of both anorexia and bulimia.

The new enhanced therapy details of which were released this week, also developed by Professor Fairburn, is more potent than the earlier version and said to be suitable for more patients – with bulimia and with disorders which combine features of bulimia and anorexia, about 80 per cent of the total.

In what way is the therapy enhanced?

The simple version focused solely on the eating disorder of bulimia. The new version is more complex and simultaneously tackles problems commonly associated with eating disorders such as low self esteem and extreme perfectionism. Both versions aim to help the individual see the links between their emotions and their behaviour and work out ways to change. It enhanced therapy is also being tried with sufferers from anorexia and the interim results look "very promising". The treatment is longer and more intense than standard CBT – one 50 minute session a week for 20 weeks.

What do the experts say about it?

Professor Fairburn said: "Eating disorders are serious mental health problems and can be very distressing for patients and their families. Now for the first time we have a single treatment which can be effective at treating the majority of cases without the need for patients to be admitted into hospital. It has the potential to improve the lives of hundreds of thousands of people."

Susan Ringwood, chief executive of Beat, the eating disorders charity, said: "This research shows people can benefit from psychological therapy even at a very low weight."

Alan Cohen, spokesperson on mental for the Royal College of GPs said: "Access to this service and appropriate training for therapists to deliver this new form of treatment is very important."

What do other therapists think of CBT?

Not a lot. They protest that the therapy is getting the lion's share of attention – and funding – when it is not justified. Critics say the Government's claim that there is more evidence for CBT (in depression) than other therapies doesn't mean it is more effective. It means that the research on the other therapies has not been done.

Andrew Samuels, a psychotherapist and professor at the University of Essex, said: "What you're witnessing is a coup, a power play by a community that has suddenly found itself on the brink of corralling an enormous amount of money. Science isn't the appropriate perspective from which to look at emotional difficulties. Everyone has been seduced by CBT's apparent cheapness."

What determines the outcome of therapy?

Some researchers think that it is the patient's relationship with the counsellor and their motivation that determines the chances of success as much as the therapy itself. Professor Mick Cooper, an expert in counselling at the University of Strathclyde, said it was "scientifically irresponsible" to imply that CBT was more effective than other therapies. Forms of treatment such as person centred and psychodynamic therapy could be equally effective and were backed by small but substantial bodies of evidence. CBT may be like putting a sticking plaster on a problem rather than getting to the root of the depression, he said.

What do the patients say?

Susan Muir, 39, from Chesterfield lost 13 stone by dieting and exercise. But once she had acvhieved her goal she found herslf locked into a pattern of binge eating and obsessive exercising. She said: "The CBT helped he realise what I was doing and turned those irrational thoughts into rational ones. It helped me with my self esteem and made me feel very positive."

Should people with eating disorders be offered cognitive behavioural therapy?

Yes

*Two thirds of sufferers experience sustained benefits and many more show lasting improvement

*The treatment is virtually free of side effects and requires no special equipment or resources

*Eating disorders have the largest mortality rate of any mental disorder, by suicide or starvation

No

*The difficulty with eating disorders is getting sufferers into treatment, by which time it may be too late

*Representatives of rival therapies say the benefits of CBT have been significantly overstated

*Some research suggests the relationship with the therapist is more critical to success than the therapy

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments