The enemy within: People who hear voices in their heads are being encouraged to talk back

It may not always be a sign of mental illness or need treating with medication

One night, during her first year at the University of Sheffield, Rachel Waddingham struggled to fall asleep. She could hear three middle-aged men she didn’t know talking about her downstairs. “They were saying, ‘She’s stupid, she’s ugly, I wish she would kill herself’,” she remembers. “I was angry and went down to challenge them, but no one was there. They kept laughing and saying, ‘She’ll never find us.’”

The voices became a recurring presence, providing an aggressive, unsettling commentary on her life. Waddingham came to believe that they were filming her around the clock, and became paranoid. When she had a neck ache, she assumed a tracking device had been planted under her skin. At the supermarket, the voices would ask each other questions like “Does she know what she’s buying?” – leading her to reach sinister conclusions. “I worried they might have poisoned the food,” she says. “I’d come back with orange juice, milk, bread and cheese, because it’s all I could work out was safe.”

Waddingham turned to alcohol to cope, and avoided friends because she feared that “The Three” would secretly film them as well. Months later, she dropped out of the university and moved into a bedsit, too afraid to eat or bathe. A doctor eventually admitted her into a psychiatric hospital, where she was diagnosed with schizophrenia and put on a cocktail of drugs. During her eight months in the hospital, the voices faded, but the side effects of the medication made life intolerable.

Waddingham gained more than 65 pounds and developed diabetes. Her eyes would roll involuntarily, and she struggled with akathisia, an overwhelming sense of restlessness that caused her to shuffle from foot to foot. Suicide attempts followed, and she felt “like a walking zombie”. Because she was no longer hearing the voices, she was released from the hospital. And now, at 36, she is still on the meds (though she is slowly weaning herself off them).

Research suggests that up to one in 25 people hears voices regularly and that up to 40 per cent of the population will hear voices at some point in their lives. But many live healthy and fulfilling lives despite those aural spectres.

Recently, Waddingham and more than 200 other voice-hearers from around the world gathered in Thessaloniki, Greece, for the sixth annual World Hearing Voices Congress, organised by Intervoice, an international network of people who hear voices and their supporters. They reject the traditional idea that the voices are a symptom of mental illness. They recast voices as meaningful, albeit unusual, experiences, and believe that potential problems lie not in the voices themselves but in a person’s relationship with them.

“If people believe their voices are omnipotent and can harm and control them, then they are less likely to cope and more likely to end up as psychiatric patients,” says Eugenie Georgaca, a senior lecturer at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and the organiser of this year’s conference. “If they have explanations of voices that allow them to deal with them better, that is a first step toward learning to live with them.”

The road to this form of recovery often begins in small support groups run by the worldwide Hearing Voices Network (HVN). Founded in the Netherlands in 1987, it allows members to share their stories and coping mechanisms – for example, setting appointments to talk with the voices, so that the voice-hearer can function without distraction the rest of the day – and above all gives voice-hearers a sense of community, as people rather than patients.

A central premise of HVN is that these voices frequently emerge following extreme stress or trauma. Research bears that out: at least 70 per cent of voice-hearers are thought to have experienced some form of trauma. The characteristics of voices vary widely from person to person, but they often mimic the sound and language of abusers or their victims: demonic and frightening, or angelic and friendly.

Waddingham, for instance, now hears 13 voices. Among them are Blue, a frightened but cheeky three-year-old; Elfie, an angry adolescent; Tommy, a teenage boy who criticises her speech; the Scream, a female voice filled with pain and suffering (“When I first heard her, I felt so overwhelmed I was unable to leave the house”); and the Not Yets, a group of voices Waddingham is not yet ready to engage with fully. “They say very nasty things about me – abusive, sexual, violent things, which echo what I heard when I was little,” she says. “I try to think of them as frightened children that don’t yet know that it’s not OK to say those things.”

When the younger voices can’t fall asleep, Waddingham reads them bedtime stories. When voices suggest that she’s going to be harmed by a stranger, she thanks them for their concern but lets them know she is being vigilant.

Eleanor Longden tells a similar story. After leaving a psychiatric hospital with a diagnosis of schizophrenia at 18, she was assigned to work with a psychiatrist familiar with the hearing voices movement. He encouraged her to overcome her fear of her voices, which included both human and demonic-sounding ones.

Traditional psychiatry discourages patients from engaging with voices, and prefers to silence them through medication. But HVN members, like Longden, say that listening to voices is vital to calming them down. And by communicating back, Longden was able to test the boundaries of what these voices could actually do. One time, a voice threatened to kill her family if Longden didn’t cut off her toe, and she could hear a “phantom choir” laughing along with him. She refused to obey. Her family didn’t die, but the choir did go silent.

As she grew less afraid, Longden sought to unpack the messages they carried. “I started to see my experiences as a sane reaction to insane circumstances,” she says. Longden had suffered years of sexual and physical abuse as a child. Her memory is hazy, but she knows her abusers were men outside her family. When she heard a voice calling her weak for accepting the abuse, she began to read it as encouraging her to be strong and assertive. “I would say, ‘You can help me practice’ and the voice was like, ‘All right’.”

Some voice-hearers speak to their voices, while others use internal dialogue. Still others communicate by writing things down. Since the voices can manifest at any time of day, voice-hearers must think of practical solutions to deal with them without alarming colleagues and passers-by. Some choose to wear Bluetooth headsets so they can speak aloud in public without causing alarm, while others simply talk into their mobile phones.

Standing by the pool at the Hotel Philippion in Thessaloniki, the venue for this symposium, are Marius Romme and his wife, Sandra Escher. The two have spent half a lifetime listening to the trauma suffered by so many voice-hearers. Yet Romme, now 80, and Escher, 69, remain warm, optimistic and almost evangelical in their beliefs, which gave rise to the hearing voices movement three decades ago. “Voices have significance in the lives of voice-hearers and can be used to their benefit,” Romme says. “It’s not a handicap, it’s an extra capacity.”

Romme hasn’t always thought that. Starting in 1974, he ran the social psychiatry department at Maastricht University in the Netherlands and saw patients at a community mental health clinic one day a week. “All my career, I worked with people who hear voices, and I regularly prescribed medicine,” he says. He dismissed the voices as symptoms of mental illness. But a patient named Patsy Hage changed that.

Hage started hearing voices as an eight-year-old, after being severely burned. By the time she came to see Romme, she was 30 and her voices had forbidden her from socialising, leaving her isolated and severely depressed. Though tranquilisers relieved some of her anxiety, they didn’t silence the voices – and she questioned why Romme considered her mentally ill but saw nothing strange about religious faith. “You believe in a God we never see or hear,” she said, “so why won’t you believe in the voices I really do hear?”

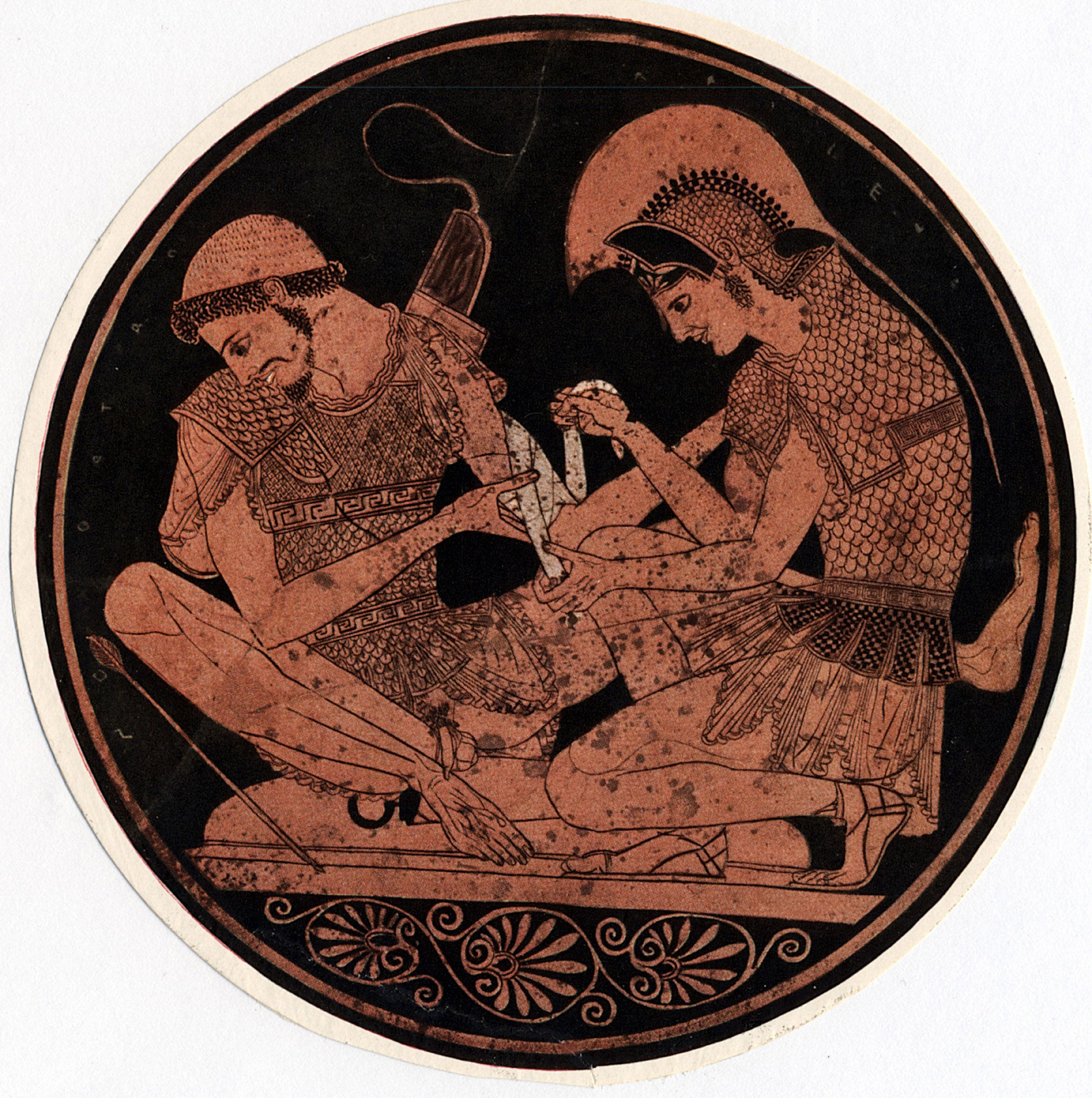

Eventually, she gave Romme a copy of The Origins of Consciousness and the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind by the psychologist Julian Jaynes. In it, Jaynes argued that hearing voices was common until the development of written language. He believed the voices heard by the heroes of Homer’s Iliad were not metaphors but real experiences. “They were voices whose speech and direction could be as distinctly heard by the Iliadic heroes,” he wrote, “as voices are heard by epileptic and schizophrenic patients.”

Attributing meaning to the voices gave Hage comfort, and Romme encouraged her to speak to other voice-hearers. With the help of Escher, a science journalist he had met years earlier, he placed a national advertisement asking voice-hearers to send in postcards with their stories. Around 700 arrived, including more than 500 from people who experienced auditory hallucinations – and got on with life just fine. “We thought that all people who heard voices would become psychiatric patients,” Escher says. “That simply wasn’t true.”

Romme and Escher’s belief that voices are not a symptom of disease but rather a response to troubling life experiences – and their treatment method of listening and responding to the voices – remains far outside the mainstream. Russell Margolis, a professor of neurology at Johns Hopkins University in the US, accepts that voices can result from trauma, but he points out that they can also be part of broader syndromes, such as bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, which demand specific treatment.

“I’m sure [Romme and Escher’s] approach can be helpful for some, but I can see some instances where it could be destructive,” he says. “One of my great concerns ... is that people can get so wrapped up in their symptom that they don’t move forward.”

Yet for many, the hearing voices approach remains an important alternative to the dominant psychiatric model. Waddingham’s voices forced her to confront her past and have helped her push past her pain. She now takes care of the voices that once tormented her. “I can feel a lot of what that voice is feeling,” she says. “If I can chill them out and they can feel safe, then I feel safe. Years ago, I would have interpreted these feelings as evidence of me being watched. Now I have a way of making sense of them that gives me some autonomy and control.”

Waddingham is now helping others do the same. She runs the Voice Collective, a London-wide project that provides services to young voice-hearers and their parents. In 2010, she began establishing hearing voices groups inside English prisons, where, according to the Ministry of Justice, 15 per cent of women and 10 per cent of men demonstrate psychotic symptoms but are left to cope on their own.

The challenges they face – alone in prison cells – make Waddingham even more thankful for how far she has come. “I feel so privileged,” she says. “I’ve travelled. I’m married. I’ve got cats. And I’ve started my own business. People always say I work too much, and I say: ‘I spent a good decade drugged up with no life. I’m recapturing some of what I lost’.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks