David Bowie was right, the music industry is learning to live in a digital world

David Bowie foresaw the financial earthquake that was to hit record labels as result of the internet. Yet there are some signs of stabilisation due to a surge of revenue from streaming. Is the model now sustainable?

Not all of David Bowie’s prophecies have been spot on. There’s no sign of the “Homo superior” shoving aside Homo sapiens yet. And we’re still waiting for the Starman to put in an appearance. But one thing the late singer-songwriter and hero to millions did get right was the impact of the internet on the music industry.

“The absolute transformation of everything that we ever thought about music will take place within 10 years and nothing is going to be able to stop it,” he said in a 2002 interview. “Music is going to be like running water or electricity.”

That’s pretty much how most young people consume music today. They used to file share and now, increasingly, they use online streaming services such as Spotify and Apple. Music has indeed become like a kind of utility.

But what about the impact of this digital revolution on the creators of music? Not long ago, some took an optimistic view that the internet would liberate artists. Bands would be able to cut out greedy record labels and sell to fans directly. Smaller acts would be able to promote themselves cheaply and effectively.

Some have tried this. For example, Radiohead left their record label, EMI, in 2005 and have released their albums themselves ever since, initially selling through their website. A decade ago Radiohead’s singer, Thom Yorke, questioned whether anyone needed a record company any more, adding that it would “give us some perverse pleasure to say fuck you to this decaying business model”.

Going it alone has hardly been a commercial disaster for Radiohead. Their albums have continued to sell strongly – and they now, of course, keep all their revenues rather than having to split them with EMI. The band recently established a new company, sparking speculation that they are raising money to finance a new album.

Other artists appear to have been empowered by the internet too. Last year Taylor Swift forced Apple to back down and pay her royalties for plays of her music on its streaming service during a three-month trial period for new users. Her clout and popularity were too much for even a company as powerful as Apple to ignore.

A group of major artists including Jay Z, Kanye West, Jack White, Madonna and Calvin Harris have clubbed together to acquire their own streaming service, Tidal.

But streaming doesn’t seem to be delivering much of a financial return to small artists. That is hardly surprising given that Spotify’s average “per stream” royalty payout is between $0.006 and $0.0084. You would need to have had a lot of songs streamed before you could even cover the costs of a recording session.

Relatively successful acts find digital returns pathetic too. Geoff Barrow of Portishead recently estimated that 34 million streams of his group’s music had earned him the sum (after tax) of £1,700.

Big artists complain about exploitation by the record labels, working in league with the streaming services. Taylor Swift wrote an article in which she urged all musicians not to “undervalue their art”.

Yet the financial interests of the superstars and the ambitious small performer are not necessarily aligned.

To understand why, consider how a small band or a new artist could possibly become as big as Radiohead or Taylor Swift. Online self-promotion works up to a point – and small acts have indeed embraced this. But to make a breakthrough, the promotion provided by the record labels still seems essential. Globally, the labels spent $4.5bn (£3.1bn) on marketing and investment in 2014 – a quarter of total revenues – according to International Federation of the Phonographic Industry. It is this investment that enables a minority of talented (or lucky) acts to hit the commercial big time.

Selling records is not, of course, the only way in which artists can make money. There are live performances too. And there have been many predictions of how the future of money in music lies in selling “the experience” to fans, rather than records.

Yet this comes back to the question of scale. If bands are to graduate to the profitable bigger venues, they still need heavy publicity and marketing to build their name. And at the moment the big labels, with their A&R people and financial resources, are the only reliable route to that. If a Bowie were starting out today then he would probably do exactly what he did back in the 1960s and try to get signed.

Despite their reputation for being rapacious, record labels are actually redistributive institutions in economic terms. They use the profits generated for them by a tiny minority of top acts to invest in breaking new acts. To this extent, the financial interests of the small artist are arguably more aligned with the record companies than those of the stars, who want to keep more of the surplus for themselves. (although whether record labels invest enough, or in the right acts, or with the right level of sustained support, are valid questions).

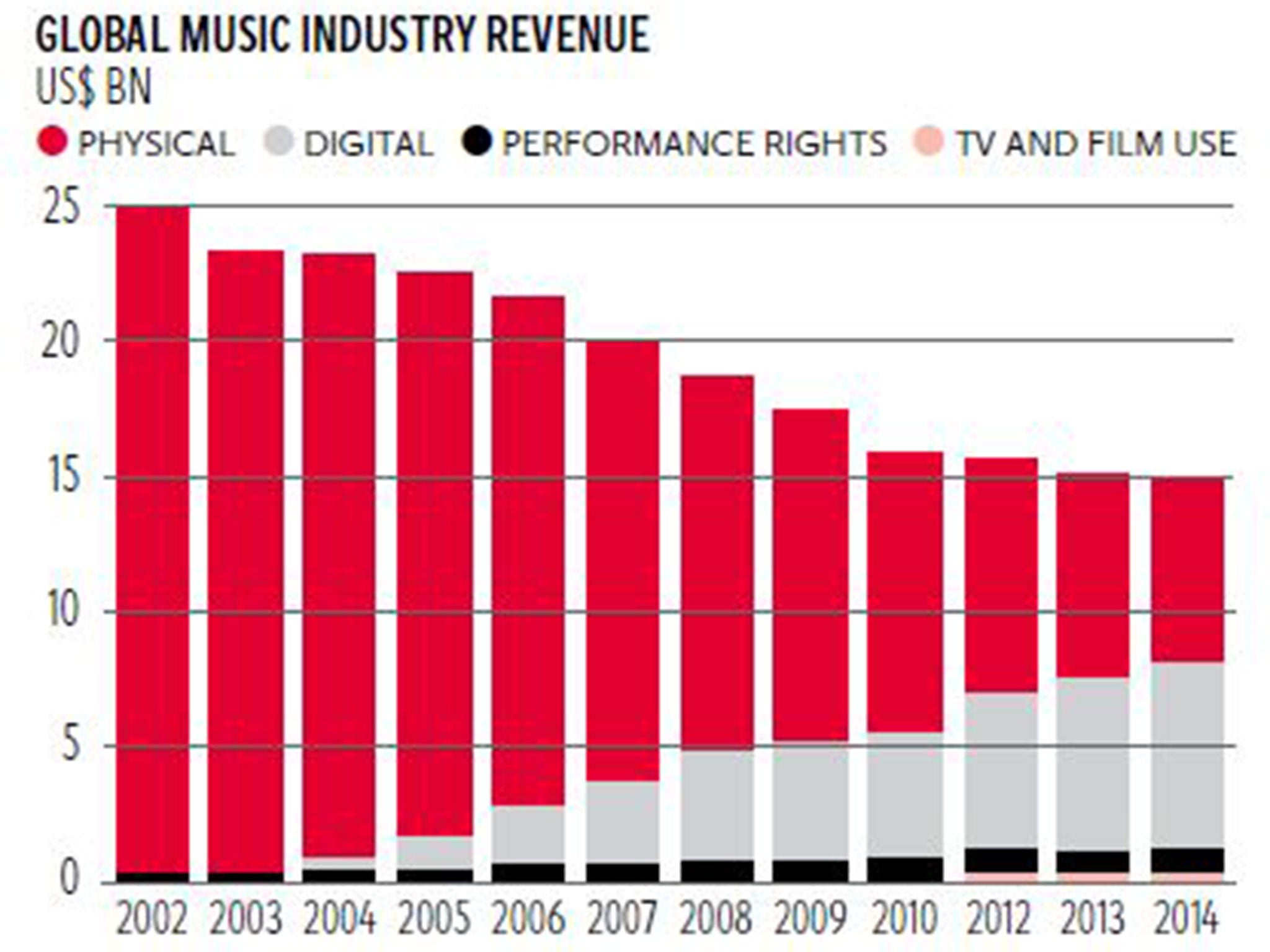

So how do the economics of the labels themselves look? The brutal impact of the internet and the MP3 file on record company revenues has been exhaustively documented. Global income peaked at around $30bn in the late 1990s and then started plummeting as digital piracy eviscerated the CD market. In 2014 sales were down to $15bn.

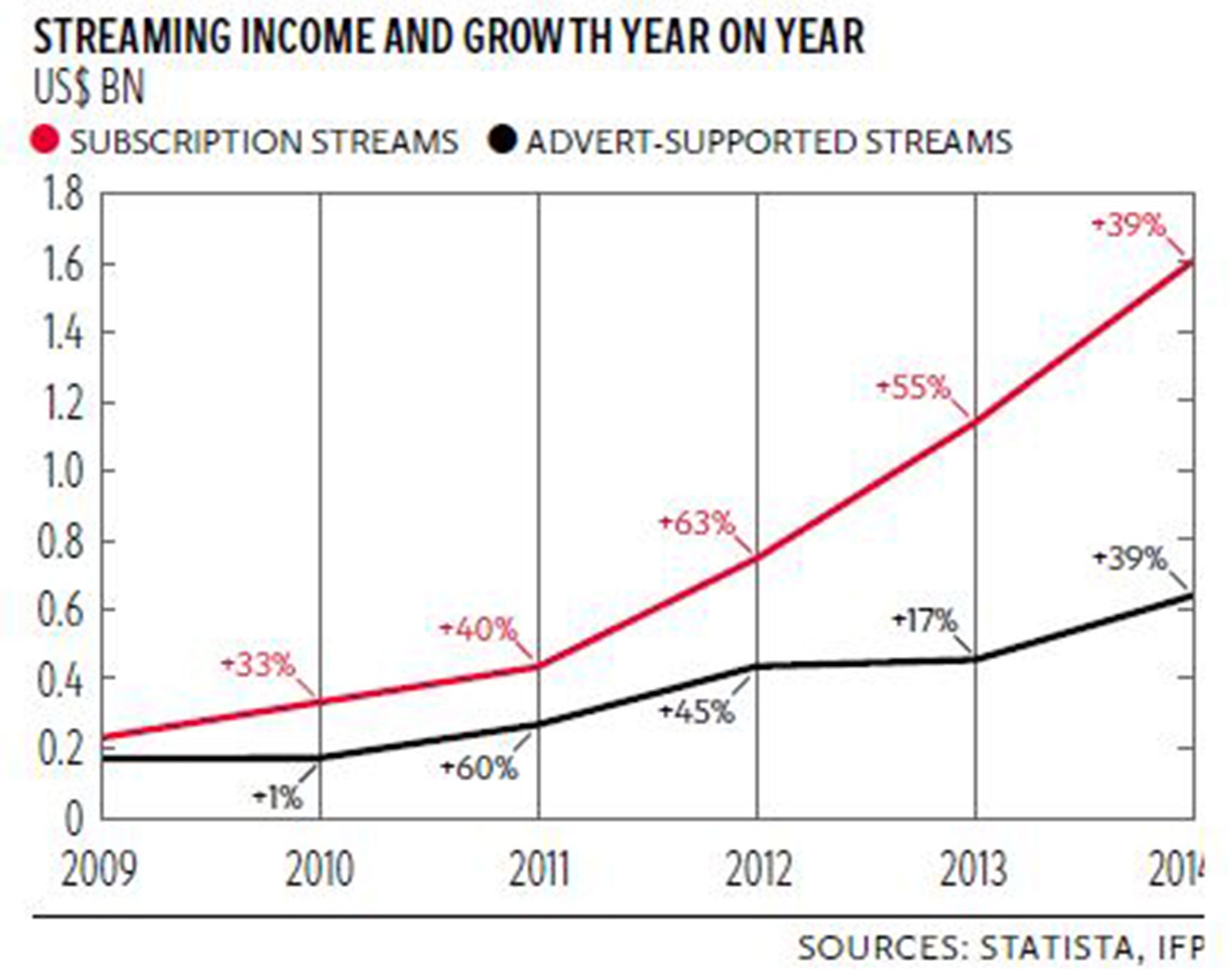

But now some see a stabilisation. Digital revenues are rising rapidly thanks to streaming royalties and legal downloads, through platforms such as iTunes. Digital revenues overtook sales of physical items such as CDs for the first time in 2014. Streaming revenue is around $2bn a year, up from zero in 2009.

If that growth trend continues, it is possible that the industry’s total revenues could start to rise again in the coming years. That could preserve the model of cross- investment of profits in smaller acts.

There are tentative signs that people are prepared to pay for the convenience of premium streaming services, rather than going through the rigmarole of illegal file sharing. Advertisers are forking out for access to viewers’ eyeballs on YouTube and listeners’ ears on Spotify.

Yet there remains profound uncertainty over the economics of the music industry. New technologies could shake things up yet again; the streamers may see their own business model disrupted.

As David Bowie would have appreciated, the one constant in the economics of music at the moment is change.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments