David Blanchflower: We're now in deflation and sorry, but it's not good news

Lots of economists are telling everyone that we shouldn’t worry about this negative inflation

It is official. The UK is in deflation. On Tuesday the Office for National Statistics confirmed that the CPI was minus 0.1 per cent, which means that prices are falling. Of course that is different from when the inflation rate falls from, say, 2 per cent to 1.5 per cent, which just means that prices are growing more slowly. For the more technically minded, that is a rate of change of a rate of change.

Core inflation, which excludes energy and food, dropped to 0.8 per cent. Worryingly, 14 European countries are also in deflation: Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Finland, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain and Switzerland. We may be stuck with bouts of deflation for a while.

The Chancellor even claimed that deflation was good news, presumably all part of his master plan. That actually stretches credibility too far even for him, given that on 18 March in his Budget speech he set the inflation target for the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) to 2 per cent. He told them they had to write to him and explain what they were doing if the CPI was below 1 per cent or above 3 per cent. That is what they dutifully did last week, when they issued their May Inflation Report. The Chancellor can’t have it both ways. He is either mistaken that deflation is good news, or was mistaken setting the target at 2 per cent; it can’t be both.

Lots of economists are telling everyone that we shouldn’t worry about this negative inflation, as it’s great. Actually we should worry, especially as it appears that Slasher is about to introduce a major new round of austerity that itself will be massively deflationary. That is what happened when he introduced austerity in 2010, it slowed the economy and pushed down on inflation.

In a letter last week council leaders representing every type of local authority in England and Wales, as part of the Tory-controlled Local Government Association, say they have already had to impose cuts of 40 per cent since 2010 and cannot find more savings without serious consequences. They wrote that “vital services, such as collecting bins, filling potholes and caring for the elderly, would struggle to continue at current levels. It would leave other parts of the public sector, such as the NHS, left to pick up the pieces of councils scaling back services.” Slasher could care less.

Slashing fiscally means loosening on the monetary policy front to compensate, so it was pretty hard to understand why the MPC’s two resident inflation hawks in the latest MPC minutes suggested they were close to voting for rate rises. Of interest, though, is in a speech last week one of them, Martin Weale, suggested that oil will push down on inflation by more than the MPC previously estimated and that the effect will persist well into next year. It suggests a downside risk to the MPC’s most recent forecast of inflation for next year.

The worry with deflation is that consumers postpone purchases in the expectation that their prices will be lower later. For a firm, prices (P) and quantities (Q) both fall, which means that revenues (P*Q) fall. This limits their ability to pay workers and wage growth falls, or even eventually wages fall. I recall Ben Bernanke saying it was deflation that keeps central bankers awake at night, not inflation, because they know what to do to fix inflation by raising rates. Central bankers have no clue how to create any inflation currently and hence how to solve deflation.

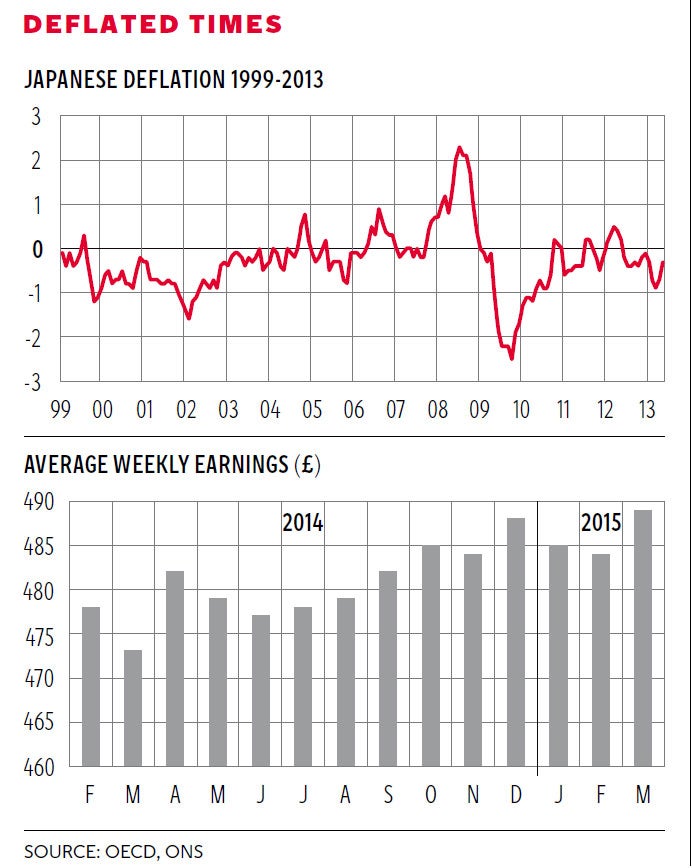

Japan’s lost deflationary decade, which actually lasted 14 years and is illustrated in the chart using OECD data, is instructive. Japan dropped into deflation of minus 0.1 per cent in February 1999, and didn’t finally exit until May 2013. Japan hopped back and forth from inflation to deflation over much of the period. Inflation averaged minus 0.3 per cent per month, and in only 20 months was it lower than minus 1 per cent, reaching its low point of minus 2.5 per cent in October 2009. Of the 172 months over this period 37 had inflation, 12 months were exactly zero, while 123 months experienced deflation. Even mild deflation can be almost impossible to get rid of.

Some commentators also went as far as to claim that wages were now growing smartly. As ever, of course, that was based on a blip in the data. The MPC has been worried about a spike coming in wage settlements, which in Q1 2015 fell back to 1.9 per cent over the last two quarters, from 2.0 per cent in Q3 2014. Plus the latest wage data published this month show that the latest jump in wage growth was simply a blip driven by a drop in the base year number that will inevitably disappear next month.

The second chart illustrates. The latest data show wages grew by 1.1 per cent, obtained by comparing wages in February 2015 (£484 per week) with wages in February 2014 (£478 per week). In March 2015 they were £489 per week, compared with £473 per week in March 2014. Note the big drop in the base, but note from the graph that next month the base jumps back up to £482 per week. Chances are next month we will see a big drop again. I will keep you posted. The MPC continues to predict wage growth of 4 per cent in 2016 and 2017. Not a chance.

We should also note that there was a big jump again this month in the number of underemployed workers, measured by part-timers who want full-time jobs. The number jumped by 26,000 on the month, and is back to levels it was six months ago. These underemployed continue to hold down wage pressure.

There has also been some debate about the extent to which foreign workers push down on wages. This debate is likely to become increasingly important given the evidence last week that net migration was 316,000, up from 209,000 in 2013, or 52 per cent on the year. Such effects appear to be small. Something that seems hard to quantify is the fear of such flows.*

If wages rise then the number of workers from the A10 Accession countries in the UK could potentially pick up further. So that means wages don’t rise because workers know that they would potentially lose their jobs to lower-paid foreign workers. With deflation, underemployment and the fear of an influx of workers from Eastern Europe, employers don’t need to raise wages. Not much good news, sorry.

*David Blanchflower and Chris Shadforth, “Fear, Unemployment and Migration”, Economic Journal, 2009, 119(535), February, F136-F182.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments