Greece debt crisis: Beware plausible stories - there are times when only statistics will do

Economic View

As a species we rely heavily on stories. Plausible narratives help us make sense of an often complex and inherently uncertain world.

For a good example, look to the law courts. Our legal system requires barristers to tell competing stories, supported by evidence, to juries about the likely guilt or innocence of a defendant. The responsibility of the jurors is then to choose what seems to them to be the more compelling story.

In civil cases, jurors are asked to reach a conclusion based on the “balance of probabilities”. But statistical probability distributions actually have little to do with this process. What matters is: which story of what happened is considered more compelling, more plausible?

And in law courts this is sensible. Imagine a hypothetical case in which a pedestrian is knocked down by a green Morris Minor in a hit-and-run accident. You own the only green Morris Minor in a 10-mile radius; a strict statistical application of “balance of probabilities” logic might suggest it was your car that hit them and that you were probably driving it too. No one in their right mind would want their fate to be decided on the basis of this kinds of calculation.

Yet while plausible stories can be useful in some contexts, in others they can do great damage. German politicians and economists have been telling their public (and themselves) a very plausible story about Greece these past five years. The tale is that the Greeks have flouted the eurozone’s rules. They manipulated their budget accounts to allow them to enter the single currency in the first place. Successive administrations in Athens then borrowed irresponsibly at low interest rates. Their economy crashed and the rest of the eurozone (Germany above all) generously rescued Greece with taxpayers’ money.

Germany and the rest of the club of creditors demanded economic reforms in return for this generosity. But Greece tried to reject these conditions. They want to be bailed out without reform. That cannot be allowed because Greece and others would simply break the rules again.

Meanwhile, argue the Germans, muddled outsiders such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) are pushing for more action that would break the rules of the eurozone, such as debt relief for Athens and even permanent fiscal transfers.

This is the essence of the German story, which melds morality with an appreciation of economic incentives.

Now consider the story of the past five years being told by an increasingly angry and disillusioned Greek population. Brutal public spending austerity imposed by unreasonable creditors has devastated the domestic economy. And now Greece is being punished and humiliated for daring to resist yet more austerity. The single currency has become a continuation of European inter-state warfare by other means – “#thisisacoup” as they say on Twitter.

Which story do you find more compelling? Don’t answer that because it’s a false choice. These are both deeply misleading stories because they both gloss over economic reality. First, consider the Germany story. A fixation on the “rules” of the eurozone is specious because the entire single currency itself represents a terrible breach of the golden rule of successful monetary unions, namely that they must allow for automatic fiscal transfers between regions in times of difficulty.

Where would the United States be if individual states needed to hold a vote every time tax revenues were due to flow to the unemployed in a poor state? What if English MPs had an effective veto over rising welfare payments owed to Scottish people in a recession? The system would plainly buckle. It’s fatuous to complain about rules not being followed when the entire game is rigged.

Now consider Greece. The narrative of victimhood glosses over the point that successive governments in Athens really were grossly irresponsible and corrupt. Tax evasion really was rampant. And the economy really does urgently need reforms to liberalise its labour markets. The notion that Greece’s misery is entirely externally imposed does not stand up to scrutiny. Yet it’s depressing how many otherwise sensible people get caught up in these two powerful stories – slipping into either the German or the Greek story of the crisis.

That said, simply splitting the difference between the two tales is not sensible either. The German view has been the greater affront to economic common sense. As the IMF says, Greece does indeed need debt relief. This is not a question of rewarding bad behaviour, as the Germans see it, but a question of bowing to reality: those liabilities will never be repaid in full.

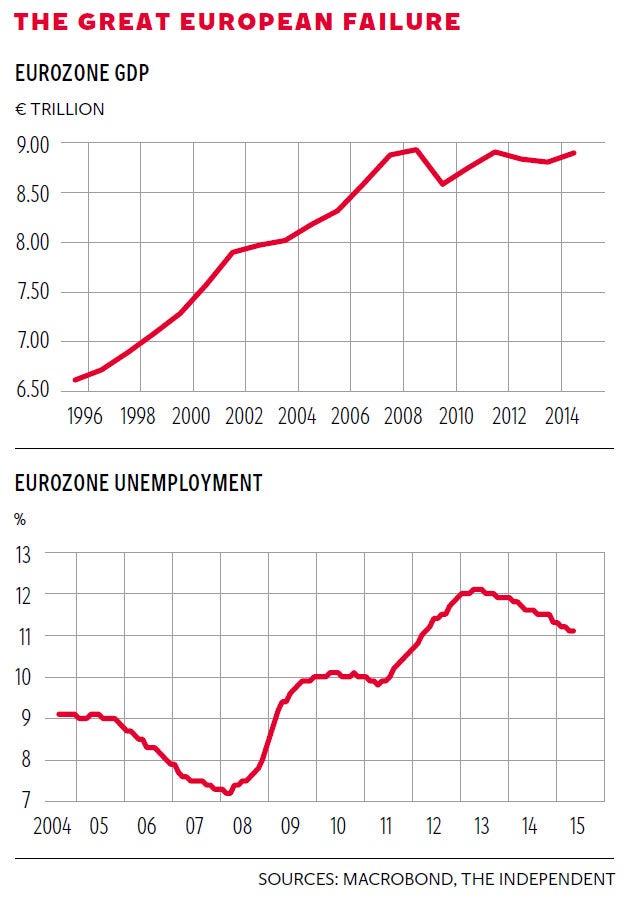

What about the idea preached by Germany that Greece is a single bad apple in an otherwise healthy single-currency barrel? This is perhaps the silliest story of all. It is the job of economic policymakers to facilitate steady GDP growth, to hold unemployment down and to control inflation. But as the first chart on the left shows, eurozone growth has flatlined for six years. The bloc’s unemployment rate has also soared, as the second chart makes clear. Parts of the eurozone are also stuck in deflation, despite the target of 2 per cent annual price growth. These statistics show that the euro, economically speaking, has been a disaster. And for tiny Greece, of course, the price has been still more severe.

Until 5 July, Yanis Varoufakis, a professional academic economist, was Greece’s finance minister. He described making economic presentations on Greece’s plight to his fellow eurozone finance ministers in Brussels as like speaking to a brick wall. “It’s not that it didn’t go down well – there was point-blank refusal to engage in economic arguments,” he said. Interestingly, his nemesis, Wolfgang Schäuble of Germany, is a lawyer.

Compelling narratives about rules and morality have been prevailing over figures and statistics.

That’s why the situation within the single currency remains a godforsaken mess. And until the plausible stories give way to economics, the sad fact is that things are unlikely to improve.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks