In some respects there was a lot of positive news in yesterday’s Bank of England Inflation Report and the latest jobs data from the Office for National Statistics.

Growth this year is now projected by Threadneedle Street to be slightly higher than it estimated in May: 3.5 per cent, up from 3.4 per cent three months ago. Meanwhile, the ONS reported that unemployment fell again to 6.4 per cent. That’s the lowest level in six years. Youth unemployment came down even more impressively, dropping 102,000 over the three months to June to just 767,000. That’s the largest quarterly fall since comparable records began in 1992.

The Bank even saw a silver lining in the weak wage growth figures of recent months, concluding that they indicate more spare capacity in the economy than it previously thought. That, in turn, suggests interest rates can be held down for longer without the risk of setting off an inflationary spiral. That’s certainly the message that markets took from yesterday’s news, with traders pushing back the date of the first expected base rate rise from the Bank until next year. Good news for people with large mortgages.

Yet there was one dark cloud looming over all yesterday’s data and forecasts: productivity. One aspect of its latest forecasts revisions the Bank did not choose to trumpet too loudly was its decision to downgrade its forecast for productivity growth over the coming three years.

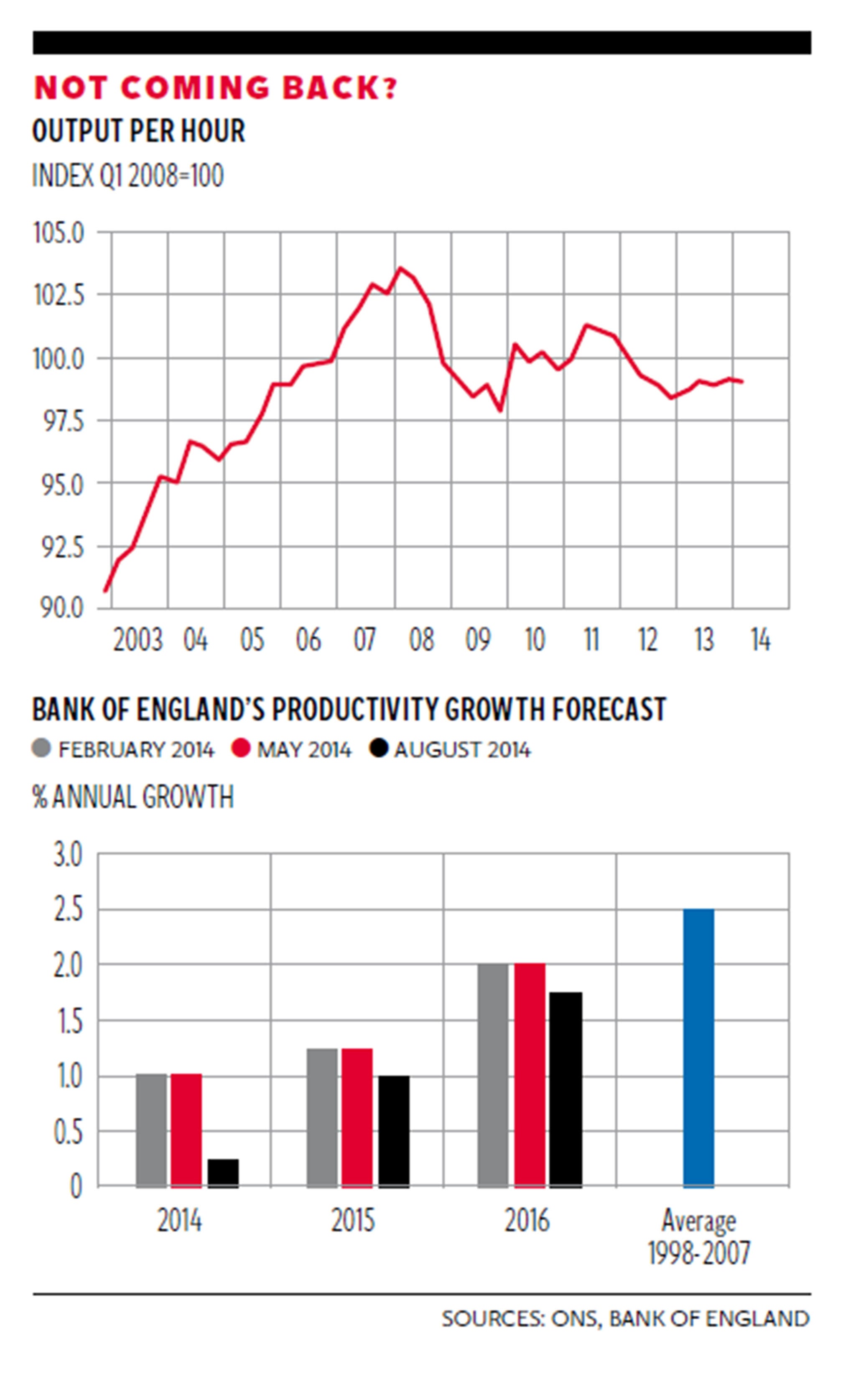

Labour productivity – or output per hour – has been dismal since the financial crisis, as the first chart shows. The index is still 4 per cent below where it was way back in the first quarter of 2008. And a 17 per cent gap has now opened up with where productivity would have been today if output per hour had grown at the same rate these past six years as it did in the decade or so before the financial crisis.

Yesterday’s employment figures suggest another productivity dip in the second quarter of 2014. Hours worked rose by 1 per cent in the second quarter. But with GDP rising just 0.8 per cent over the same period, that implies productivity declined yet again. GDP is going one way, but productivity is heading the other.

Weak productivity is, of course, the flipside of the “jobs miracle” that Britain has experienced in recent years. Strong growth in hours alongside weak-to-moderate GDP output mathematically results in falling, or poor, productivity growth.

The Bank has long been optimistic about this dismal trend coming to an end. Successive Bank forecasts have expected strong productivity growth to kick back in as the recovery progressed. But yesterday the Bank stepped away from that optimism. It slashed its estimates of output per hour growth over the next three years, as the second chart shows. Having stuck to the belief in February and May that productivity would increase by 1 per cent in 2014, it yesterday slashed that forecast to just 0.25 per cent. It also reduced the forecasts for 2015 and 2016. And note that the Bank now does not expect productivity growth to get anywhere near back to the pre-crisis trend of 2.5 per cent over the next three years, despite the relatively robust recovery.

The Bank’s Governor, Mark Carney, said yesterday that the outlook for productivity remains an “open question”. Researchers at the Bank have floated some reasons why this crucial index might have disappointed. The financial crisis might have discouraged firms from investing, something that would be expected to damage the prospects for productivity growth. Business might have been responding to higher demand by hiring workers, rather than investing in new plant and machinery. Economists call this substituting labour for capital. The Bank has even suggested the gap might partly be explained by mis-measurement of GDP or hours by statisticians at the ONS.

But Mr Carney denied yesterday that there had been “any structural break in the productivity potential of this economy – it’s something to do with the timing in terms of the recovery”. In other words, although the date has been pushed back, the return to decent productivity growth will still come eventually.

It would be easy, at this point, to make glib jokes about cults revising the date of the apocalypse when the end of the world doesn’t arrive as predicted. But the stakes are too high for that kind of nonsense.

If productivity doesn’t recover to at least the pre-trend rate it means we are set to be permanently worse off as a nation than we thought. Without productivity growth employers cannot put up wages without stoking inflation. Without a productivity pick-up the Bank will sooner or later feel obliged to put up rates to stop the economy overheating. That will crimp the GDP expansion when it has barely got going.

Moreover, no good explanation has been offered for why the productivity potential of the UK economy has been so badly damaged by the financial crisis that we can never get back to those pre-crisis growth rates of 2.5 per cent a year.

Indeed, there are quite reasonable grounds for believing that not only can we return to those rates, but that we can also fill in at least some of that yawning 17 per cent gap relative to the pre-crisis trend. That is, after all, what has always happened in the wake of previous recessions, even the protracted slumps of the inter-war years.

Mr Carney, in short, is right to keep the faith.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments