Three charts that show Iceland's economy recovered after it imprisoned bankers and let banks go bust - instead of bailing them out

"It is dangerous that someone is too big to investigate - it gives a sense there is a safe haven."

Iceland’s finance minister has announced a 39 per cent tax on investors looking to take their money overseas.

The country has imposed the tax to prevent it hemorrhaging money as it loosens bank laws imposed six years ago, when Iceland made the shocking decision to let its banks go bust.

Iceland also allowed bankers to be prosecuted as criminals – in contrast to the US and Europe, where banks were fined, but chief executives escaped punishment.

The chief executive, chairman, Luxembourg ceo and second largest shareholder of Kaupthing, an Icelandic bank that collapsed, were sentenced in February to between four and five years in prison for market manipulation.

Bailing on bail out

While the UK government nationalised Lloyds and RBS with tax-payers’ money and the US government bought stakes in its key banks, Iceland adopted a different approach. It said it would shore up domestic bank accounts. Everyone else was left to fight over the remaining cash.

It also imposed capital controls restricting what ordinary people could do with their money– a measure some saw as a violation of free market economics.

The plan worked. Iceland took a huge financial hit, just like every other country caught in the crisis.

This year the International Monetary Fund declared that Iceland had achieved economic recovery 'without compromising its welfare model' of universal healthcare and education.

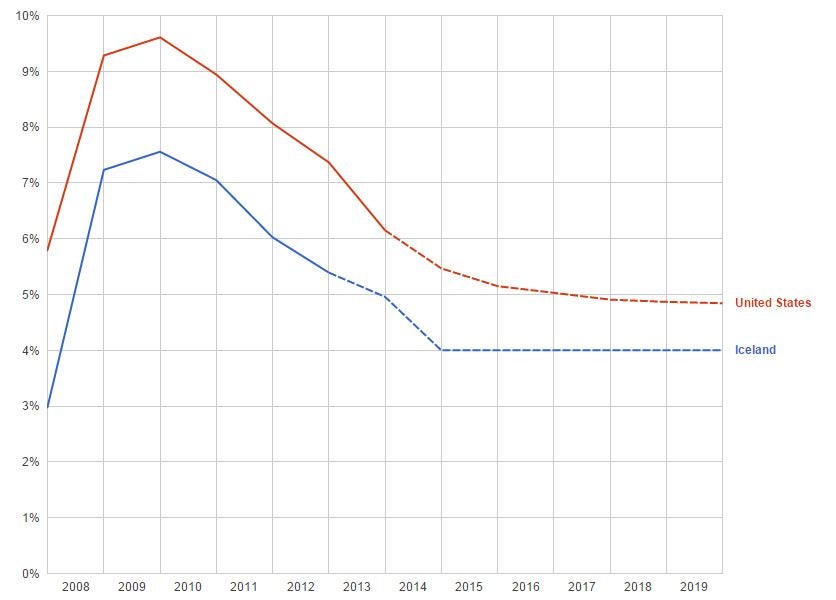

Other measures of progress like the country’s unemployment rate, compare just as well with countries like the US.

Iceland's unemployment rate compares well

Rather than maintaining the value of the krona artificially, Iceland chose to accept inflation.

This pushed prices higher at home but helped exports abroad – in contrast to many countries in the EU, which are now fighting deflation, or prices that keep decreasing year on year.

This year, Iceland will become the first European country that hit crisis in 2008 to beat its pre-crisis peak of economic output.

With the reduction of capital controls – tempered by the 39 per cent tax – it continues to make progress.

"Today is a milestone, a very happy milestone," Iceland’s finance minister Bjarni Benediktsson told the Guardian when he announced the tax.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments