Fertility 'breakthrough' as human eggs grown in lab for first time

Scientists crack elusive technique for maturing eggs outside the ovaries

Human eggs with the potential to become fertilised embryos have been grown in a laboratory for the first time in a breakthrough that could unlock future fertility treatments.

In a landmark development, scientists have been able to replicate the process where egg cells mature in the ovaries outside of the body.

Using strips of ovarian tissue removed in a biopsy, it represents an advance on IVF (in vitro fertilisation), where a mature egg is fused with a sperm in the lab and the fertilised embryo is implanted.

Under the new process, in vitro maturation (IVM), the maturation of eggs takes place in the lab, raising the prospect of new hope for women who lose their fertility.

The study’s senior author, Professor Evelyn Telfer of the MRC Centre for Reproductive Health at the University of Edinburgh, told The Independent: “If we can show these eggs are normal and can form embryos, then there are many applications for future treatments.”

Simply having a process to study egg development in the lab is a major benefit for researchers, and her team is now focused on “optimising” their technique and seeing how healthy the embryos are.

If shown to be effective, it could help women who do not not ovulate naturally and therefore do not respond to IVF, and could preserve fertility in cancer patients.

Young girls, in particular, have very few options for preserving their fertility before chemotherapy or radiotherapy.

Currently the ovarian tissue is stored in the hope that this could be transplanted back when they’re in remission to restore some fertility.

“That could be a risky business,” said Prof Telfer. ”Many of these young girls have blood-borne cancers and if some of the abnormal cells are there you’d never take the risk of transplanting it back.

“So this kind of technology could then be applied.”

Theoretically it could even be applied in post-menopausal women, though it would be difficult to get a piece of ovary that contains enough egg cells.

“The honest answer is we really don’t know at this stage,” said Prof Telfer. “It’s proof of concept at the moment, we have a lot of work to do and safety always has to be the priority”.

While the eggs in the study are at the final stage of maturation, it is not known whether they could form a healthy embryo. Prof Telfer said they have a significant ethical and regulatory process ahead before they can attempt fertilisation.

Independent experts agreed there would be several years before this treatment would appear in fertility clinics, but said it may be looked back on as a “seminal advance”.

The research effort is the culmination of 30 years of international collaboration, which has previously only demonstrated start-to-finish IVM in animals, where ovarian tissue samples are much more plentiful.

Several teams, including Prof Telfer’s, have previously been able to complete parts of the maturation process.

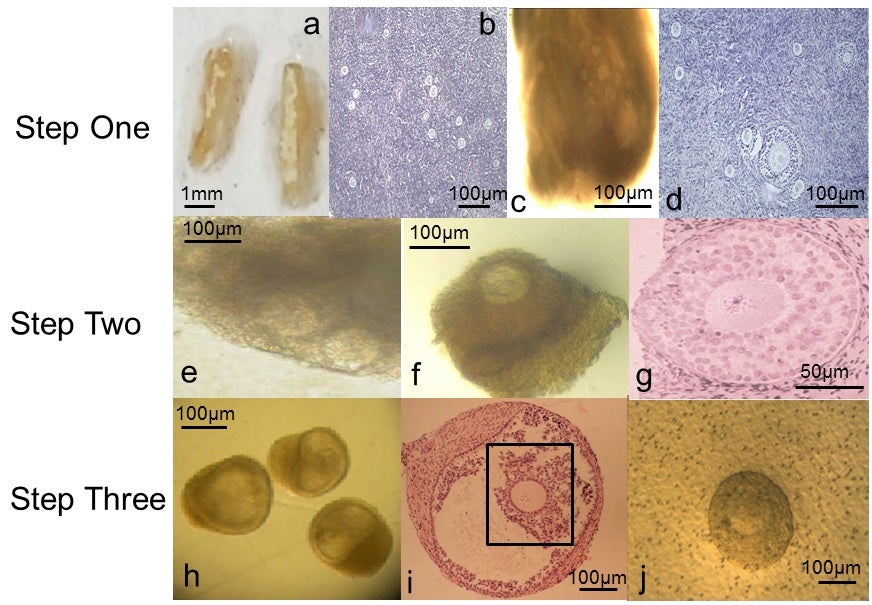

The latest advance, published in the journal Molecular Human Reproduction today, began with ovarian tissue from 10 women, aged between 25 and 39, who were giving birth by caesarean section.

Women are born with millions of immature eggs, contained within follicle cells in the ovary, but only a few hundred are released over a lifetime.

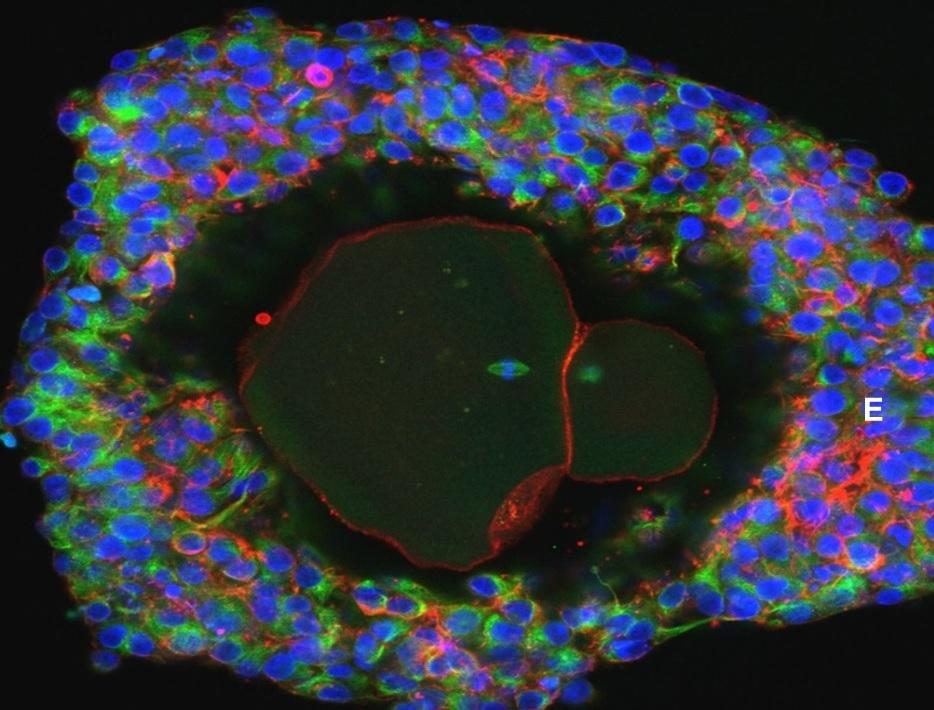

These follicle cells, and the eggs within, are very sensitive to hormone levels and other environmental factors at each stage of development.

So, in conjunction with medical experts, the Edinburgh team had to replicate these conditions.

The biopsied ovarian tissue was first examined to remove any follicles that had already begun the maturation process, before the growth phase began.

When the follicle had matured sufficiently, the egg was squeezed out “under gentle pressure” for the final stage of development.

From numerous primary follicles they matured just 54 eggs and were able to get nine that might be capable of forming a healthy embryo and growing a baby.

While this remains a lot less efficient than IVF, where women take regular follicle stimulating hormone injections to mature multiple eggs and give them the best chance of pregnancy, it could be another route where IVF isn’t an option.

“This is an elegant piece of work, demonstrating for the first time that human eggs can be grown to maturity in a laboratory,” said Dr Channa Jayasena, a member of the Society for Endocrinology and clinical senior lecturer at Imperial College London, who was not involved with the research.

“It would take several years to translate this into a therapy. However, this is an important breakthrough, which could offer hope to women with infertility in the future.”

Professor Daniel Brison, scientific director of the Department of Reproductive Medicine, University of Manchester, agreed, saying: “This could pave the way for fertility preservation in women and girls with a wider variety of cancers than is possible using existing methods.”

But Professor Robin Lovell-Badge, group leader of the Francis Crick Institute, said the results showed limitations in the technique at present.

There were signs the embryos might be abnormal and their chances of being fertilised are unknown, and the ovaries of girls pre-puberty “will be at an early stage and perhaps quite different from those in an adult”, he said.

He added: “While this work may contain an important step, many more will have to be taken to reach the destination. But you can’t make an omelette without breaking eggs.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks