The prisons inspectorate: When the recommendations are ignored what is the point?

Inspection of HM prisons costs taxpayers as much as £3.5m a year. It’s a small sum in the grand scheme of things, but when it comes to improving our crisis-hit prison system, is it worth the investment?

A month ago the Ministry of Justice released its latest Safety in Custody quarterly bulletin showing that “safety” in our prisons, in terms of self-harm, assaults on prisoners and staff, had again all reached new record highs – and that efforts to tackle the problem had plumbed new depths too.

The latest figures showed that in the 12 months to March 2017:

- Self-harm reached a record high of 40,414 incidents, up 17 per cent from the previous year.

- Assaults also reached a record high of 26,643 incidents in the period, up 20 per cent from the previous year. Of these, 3,606 were serious assaults, up 22 per cent from the previous year.

- There were 19,361 prisoner-on-prisoner assaults, up 16 per cent. Of these, 15 per cent were serious, up 21 per cent from the previous year. Prisoner-on-prisoner assaults saw a 1 per cent increase in the latest quarter.

- There were 7,159 assaults on staff, up 32 per cent and serious assaults on staff have trebled since 2013, reaching 805. Assaults on staff increased by 5 per cent in the latest quarter, reaching a new quarterly record high.

- There was some good news too, there were 316 deaths in prison custody in the 12 months to June 2017, down by six on the previous year.

But, good news or bad, the fact is that hardly anyone batted an eyelid. To many observers these are just numbers – except that they’re not.

Each single figure represents distress or devastation brought to the lives of real people, who live or work in the prison system, and to their family and friends too, who tens of thousands of times a year have to pick up these pieces.

Last week HM Inspectorate of Prisons (HMIP) published its shocking report on Aylesbury young offenders institute, revealing a prison spiralling dangerously out of control. Inexperienced prison officers, far too few in number to do the job properly, were overwhelmed trying to deal with volatile and frustrated young men locked up for long periods with no activity and too little sentence progression.

The report gained some media attention, largely because the prison sits in the constituency of David Lidington, the Justice Secretary, and I heard many people praising HMIP for yet again showing its value. I was not one of them.

HMIP, when it inspects our crisis-hit prison system, costs the taxpayer around £3.5m a year – it’s hardly a huge amount in the grand scheme of things, but what do we get for it is my question? Inspection reports where, in the majority of cases, the text could be cut and pasted from one depressing report to the next?

It’s become tempting to believe that once you’ve read one, you’ve read them all. The majority simply rediscover exactly the same problems around the country reciting what we already know; our prison system is in melt-down. Occasionally HMIP does find examples of good prisons, it’s just that they are few and far between, and becoming rarer with each passing month.

My issue with the Inspectorate is not with the theory of what they do, so much as the practice of what we achieve from them doing it. HMIP published 28 reports in the 12 months to August 2017, detailing inspections where they turn up, unannounced, get under the prison’s skin and with surgical skill turn the prison inside out, literally.

They are good at what they do, make no mistake about that, and given the range of experts across the various custodial skills disciplines among their inspection teams, it’s hardly surprising they are not easily hood-winked. I have yet to find one HMIP recommendation that doesn’t make sense.

No. It is not their reports or their recommendations that are the problem; it’s the fact that hardly anyone takes a blind bit of notice of them. Ignoring HMIP recommendations as to how a failing prison can make progress, has now become so ingrained in prison service culture, it’s now almost to be expected.

Just look at the titles of their recent Annual Reports:

In 2013/2014: “prisons less safe”, warns Chief Inspector.

In 2014/2015: “prisons decline across all areas”, warns Chief Inspector.

In 2015/2016: “prisons unacceptably violent and dangerous”, warns Chief Inspector.

In 2016/2017: “prison reform is impossible until jails become safer”, warns Chief Inspector.

The Chief Inspector needs to stop “warning” and make sure something is done about it – or what is the point of him? I ask again, what are we actually getting for our 3.5 million quid a year – what is actually changing?

An examination of the Inspectorate’s recent work brings the issue into even sharper focus. When HMIP inspects our prisons they do so judging them against what are known as the four Healthy Prisons tests – set out in its “Expectations” publication.

Safety is the first one, meaning HMIP expects to find prisoners, particularly the most vulnerable, are held safely. Respect comes next; where they expect to find that prisoners are treated with respect for their human dignity. Purposeful Activity is third on the list, meaning that prisoners are able, and expected, to engage in activity that is likely to benefit them in terms of skills training and offending behaviour programmes. Finally there is Resettlement, looking to ensure that prisoners are prepared for their release into the community and effectively helped to reduce the likelihood of reoffending – from next month HMIP are rebranding this ‘Resettlement” test as “Rehabilitation and Release Planning.”

Where HMIP finds failings against these tests it makes recommendations intended to be acted upon to bring the prison back up to professional standards that ensure safe custody, promote rehabilitation, and reduce reoffending.

It was when I read the report on Aylesbury and realised that of the 74 recommendations HMIP made at Aylesbury two years ago, just 14 had by this inspection been achieved (19 per cent), that I carried out an assessment of the 28 prison inspections reports published by the Chief Inspector in the year to August 2017.

What I found was shocking – and it made me realise that HMIP is being made to look like a professional laughing stock. But it’s no laughing matter.

Every single prison, which had an HMIP inspection report published in the year to August 2017, failed miserably to implement vital custodial recommendations that were made the last time HMIP visited – recommendations designed to keep prisoners and staff safe, prevent future victims of crime, made years earlier, but which are very largely simply ignored.

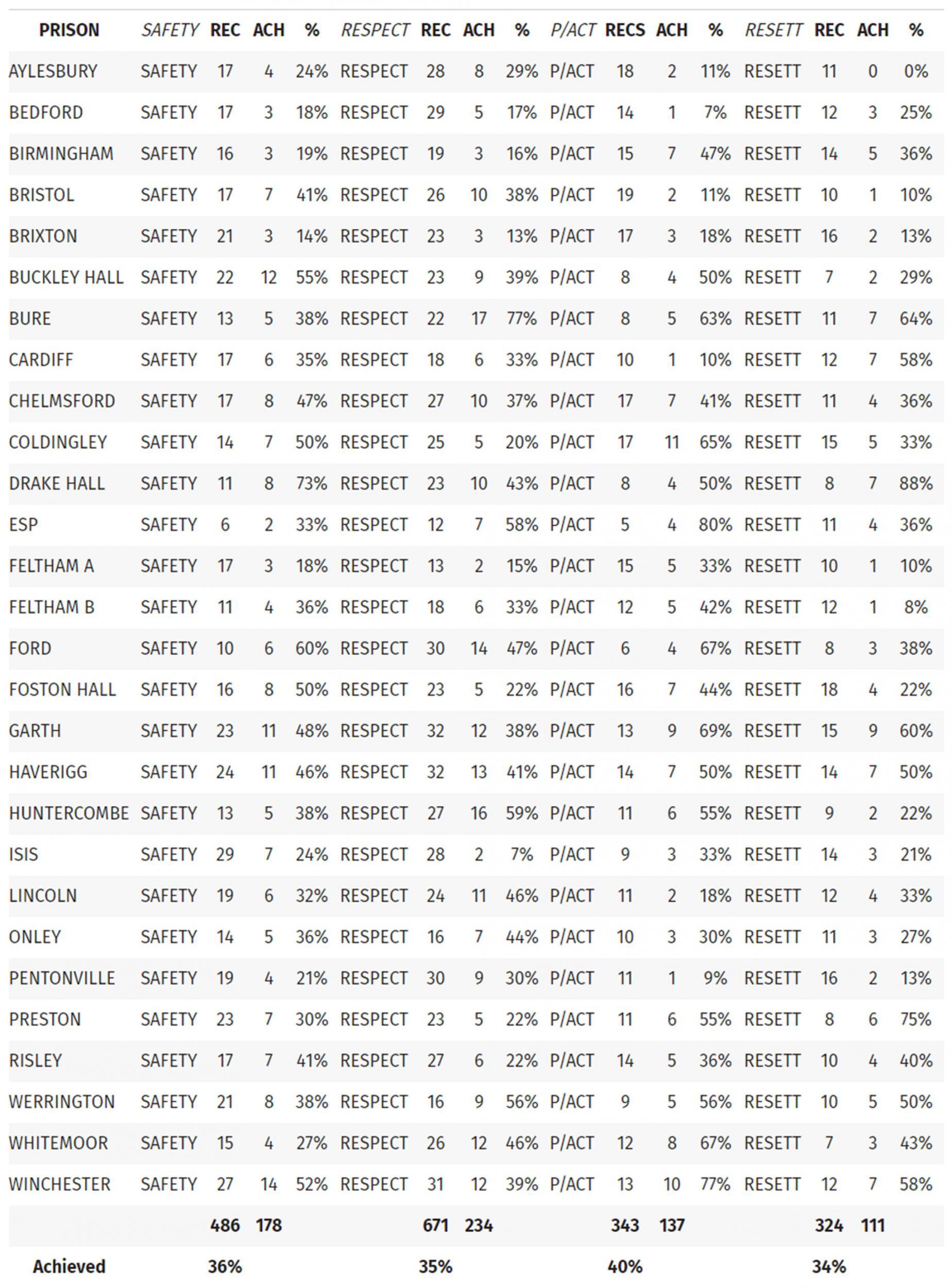

Prisons are failing to implement these recommendations not because they want to treat prisoners and staff with contempt but simply because they have neither the staff, money or time to do it. The table below shows, for each of the prisons listed, whose inspection reports were published in the year to August 2017, against each of the four healthy prison tests, the number of recommendations made against each test at the last inspection, how many had been achieved by this latest inspection – and the shamefully low percentage that it represents.

Overall, out of a total of 1,824 recommendations HMIP made the last time they visited these 28 prisons, when they came back, only 660 had been achieved; just 34 per cent.

And let’s be honest, given the years that pass between inspections, they range from two to five years, it’s not as if the prisons concerned have not had time to implement the recommendations is it? If prisons can’t manage to implement vital safety recommendations in two to five years in full, the temptation is to believe that they’re never going to do it.

HMCIP needs legal powers to enforce compliance – if prisons can just ignore HMIP recommendations without penalty or question, what on earth is the use of them in the first place?

Prison staff have the right to come to work in safe environments, and they have the right to go home at night in the same condition that they arrived for work in.

The courts do not send people to prison so they can be subjected to 20,000 assaults a year, kept in conditions that should cause every decent person to hang their head in shame – and neither does the public expect they will inevitably become the next victim of crime because the Ministry of Justice thinks it can run a modern, safe, humane and reforming prison system on tuppence ha’penny.

HMIP is worthy, it is a valuable asset and it’s remarkable value for money too. But there has to be more to this than simply producing repeated reports, where they keep finding the same failings, in the same prisons, and where they are ignored in the same way, inspection after inspection. We need a Prisons Inspectorate that is bold, forceful, and truly independent.

One that holds press conferences with each report it publishes, confronting publicly ministers with the misery they find, and which makes clear these continued failings will not be tolerated.

The sad fact is that, as things currently stand, the whole lot of them in HMIP could resign tomorrow, and we’d be no worse off – indeed arguably by saving three or four million quid a year we would be better off.

The taxpayer deserves better for its millions spent on this valuable service than they are getting. So too do those who live and work in our prisons, who suffer these attacks and conditions, and it’s time to demand better from an Inspectorate that likes to trumpet its independence, but which in truth could actually do a far better job of delivering it in practice, if they only had the cahunas to do so.

Mark Leech is the Editor of The Prisons Handbook for England and Wales @prisonsorguk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks