Britain's own Watergate scandal (shurely shome mishtake? Ed)

Francis Wheen tells Ian Burrell of a decade of paranoia when all journalists dreamed of being the next Woodward and Bernstein

It was to be the "British Watergate"; and the man promising to be the key "Deep Throat" informant had been the nation's prime minister only a few weeks previously. Two BBC reporters stood before Harold Wilson in his private home and waited for instructions on how they should pursue the story that would make their names as this country's Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein.

"I see myself," Wilson then began, "as the big fat spider in the corner of the room. Sometimes I speak when I'm asleep. You should both listen. Occasionally when we meet I might tell you to go to the Charing Cross Road and kick a blind man standing on the corner. That blind man may tell you something, lead you somewhere."

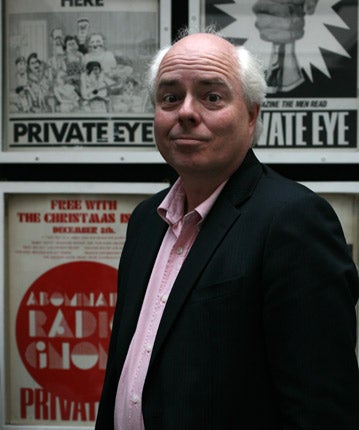

Barrie Penrose and Roger Courtiour probably realised then that this 1974 assignment was going to be less than straightforward but for the next 18 months they doggedly pursued the instructions of the Big Fat Spider. "These poor old gumshoes traipsed around the country and kept coming up with dead ends," recalls Francis Wheen, sat in an office at the top of the creaky staircase at Private Eye, where he is deputy editor. Wheen, 52, has included the story in his new book Strange Days Indeed, in which he explores the atmosphere of paranoia that infected Seventies politics and the media attempting to cover it.

Convinced his election defeat was the result of a dark conspiracy, Wilson's mind, according to Wheen's diagnosis, was "such a simmering goulash of half-remembered incidents and unexplained mysteries that it was impossible to tell how the ingredients had ever come together".

Private Eye found out about this BBC probe and mockingly dubbed the reporters "Pencourt", a reference to the "Woodstein" shorthand applied to the men from The Washington Post. The two British journalists liked the name sufficiently to title their subsequent book The Pencourt File, though unlike Watergate, which was made into the Oscar-winning film All The President's Men, it was not a story that excited Hollywood. As Wheen sips on a mug of black tea, he describes The Pencourt File as "a real shaggy dog story" and observes wryly that it ends by promising that the file would "remain open".

Not that he blames "Pencourt" because Fleet Street was collectively jealous of Woodward and Bernstein, who had created a fleeting heroic era for American journalists. "Everyone wanted to find the British Watergate, they were feeling slightly left out," says Wheen, who that year had joined The Guardian as an editorial assistant and found himself sat alongside the paper's star investigative reporter Martin "Sweetie" Walker. "He was rather a glamorous hippie who would come sweeping into the office with hair down to here and an Afghan and he called everyone 'Sweetie'," he remembers. "We hadn't really got our own Watergate so in the mid-Seventies you had Sweetie charging around saying 'Well, perhaps it's South African intelligence, Boss, performing dirty tricks in Britain, or sanctions-busting in Rhodesia by British corporations?'"

Such conspiracy theories were far from fanciful in the Seventies. Indeed, the starting point for Wheen's book was the memory of a conversation over a lunch in 1980 with Mike Molloy, a senior executive on the Daily Mirror, and Bruce Page, a Sunday Times investigative veteran who edited the New Statesman. The pair told the young Wheen how they had been summoned to a dinner in 1975 by Sir Val Duncan, chairman of the mining conglomerate Rio Tinto Zinc, and invited to participate in a coup d'état along with the retired generals and captains of industry also present at the meal.

"They had this lavish dinner and then Sir Val Duncan said: 'It's time to tighten our belts, the country is becoming ungovernable and is on the verge of anarchy we are going to have to step in very soon and take over'." He then addressed the group of journalists, which also included the Daily Telegraph editor Bill Deedes and the BBC's political chief Peter Hardiman Scott. "Obviously, we will have to close down all the newspapers so they don't sow dissent but we will have to have a newspaper to reassure people to go about their normal business and not to panic," says Wheen, paraphrasing the RTZ chairman.

Page and Molloy, both supporters of the ruling Labour Party, left the gathering just as the Telegraph editor was asking for further details of the plan. "Full marks to Deedes," says Wheen, who writes Private Eye's "Hackwatch" column. "The duty of a reporter was to stay there and find out more." But the only subsequent report of the treachery was a brief item in the Telegraph's City pages, noting that, in addition to its core business activities, Rio Tinto Zinc "is also in a position to furnish a coalition government should one be required". Though Wheen says the Seventies are "unimaginable" to many modern journalists and have "fallen down a pre-digital memory hole", he points out in the book that "The world we now inhabit... was gestated in that unpromising decade." The first call on a handheld mobile phone was made in 1973 in New York by Motorola's Martin Cooper, and the first personal computer, the MITS Altair, appeared on the cover of Popular Electronics in 1975.

Not that Private Eye has had much time for such advances. While other periodicals attempt to cling on to circulation by offering readers luxurious textures of paper, the Eye prefers to appear like a "student magazine" assembled with scissors and cow gum. "Unfortunately it is now laid out on computer but it might as well not be," says Wheen, who has been at the satirical title for two decades. "We kept manual typewriters for longer than any other publication but we eventually capitulated." It comes as a surprise to find, as Wheen digs out some of his favourite Hackwatches, a feature he started in 1991, that the Eye's archive is computer-

based, rather than a collection of yellowing cuttings. His first target was Daily Mail diarist Nigel Dempster, whose copy he summarised to show its inanity: "21 May: Lady Edith Foxwell trips on a step and hurts her heel." Dempster made Hackwatch four times.

Wheen, a biographer of Karl Marx and the Labour politician Tom Driberg, has worked for numerous publications including The Independent on Sunday. In a recent diary for the Financial Times he boasted that Private Eye, with its circulation of 206,500, is "by several furlongs the biggest-selling current affairs magazine in Britain". It has done this with its student production values and almost no online presence. In those terms, it has remained in the pre-digital decade that Wheen has been studying. He says that other media figures, such as The Guardian's editor Alan Rusbridger, had implored the Eye's editor Ian Hislop to make the magazine's contents available on the internet for free.

The advice has so far been not much more valuable than that of the Big Fat Spider. "Ian and I were just looking at each other saying 'Why would anyone bother to buy the magazine if we put it all on the website?'"

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks