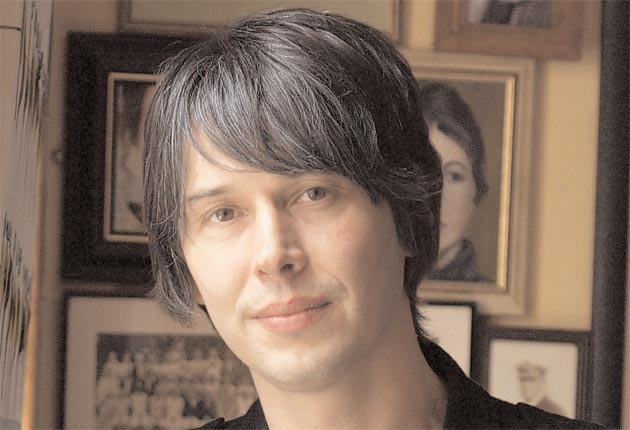

Brian Cox: Stars in his eyes

The one-time member of D:Ream has proved a dream signing for the BBC – a presenter with the looks, charm and expertise to turn millions of viewers on to the joys of science

There was a time when science on the BBC was explained by the reassuring voice of an anonymous narrator with the clipped accent of a Home Counties doctor.

Today we have the phenomenon of the scientist-presenter who brings personality and professional experience – as well as regional vowels – to the small screen. There is perhaps no better example than Professor Brian Cox, the Lancashire lad and pin-up of particle physics whose new four-part series,Wonders of the Universe, begins tomorrow night.

It is no exaggeration to say that Oldham-born Cox has propelled television science to new heights of popularity and, whisper it, may have even succeeded in making physics cool. His first series, Wonders of the Solar System, attracted five million viewers, more than three times the usual audience for a programme of this kind. Much is riding on his latest journey into the mysterious realms of time, space and cosmology.

The popularity of Cox is especially notable among female viewers. He has been credited with bringing the "sigh" back into science. With artfully floppy hair, gleaming skin and an infectious smile, the studmuffin of science has proven that you don't have to have to be bald with bad teeth to be a boffin.

One female journalist who interviewed him recently explained her fascination with the 43-year-old Manchester University academic: "When I look at Professor Brian Cox, what I want to do is to clutch him to my bosom in an entirely non-sexual way and mother him. There's the soft, northern burr, and the impossibly youthful face that makes him look about 15." Other female fans have expressed less platonic yearnings for the mop-headed science presenter who admits that he finds it hard to get out of bed in the morning.

It also helps that Cox has had an edgy youth. He joined a local Manchester rock band called Dare after school and made an album in Los Angeles before it all fell apart in a drunken brawl in a Berlin bar. He applied to Manchester University at the relatively late age of 23 and subsequently managed to get a first-class degree in physics. But his rock music career continued as a keyboards player for the band D:Ream, whose hit single "Things Can Only Get Better" went to No 1 in January 1994.

The song was famously adopted by New Labour during the 1997 election and Cox played at the euphoric post-election party in London. But, in the end, the rock business was not for him. He went on to do a doctorate in particle physics and now works on one of the experiments at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at the particle physics centre, Cern, near Geneva. He says he has no regrets about choosing a career where he uses his brain rather than his musical talent – now he prefers listening to Mahler.

However, a second career as a science communicator beckons as a direct result of the public interest in LHC prior to its official opening. When Cox began to appear before the media to explain the important of the physics behind the LHC, his televisual presence was immediately spotted by producers at BBC Horizon, who quickly signed him up. He has never looked back.

Part of his appeal lies in the enthusiasm he shows for explaining the wonders of science, and physics in particular. His expertise is not inq uestion. Anyone who thinks Cox has got where he is purely on telegenic grounds is mistaken. His delivery is helped by an almost permanent smile, combined with his down-to-earth Lancastrian vowels. Some off-cuts of his latest series can be viewed on YouTube; there is one intriguing moment filmed in a Tucson diner where Cox is getting increasingly exasperated with his producer, who wants him to explain the movement of a gravity wave through the space-time continuum. After repeatedly trying to explain how the wave moves through space to the unconvinced producer, Cox loses it. "Are you being weird now," he says. "Can someone else other than him explain to me why this isn't correct?"

It was a rare moment when the famous smile turned to the nearest thing Cox does to a frown. There is wonderful spoof of Cox's grinning enthusiasm on another YouTube clip, where real footage of him looking up at the sky is overcut with the voice of someone with a similar Madchester accent: "Sometimes, I look at the stars and I wonder: what the fuck is going on?"

Cox was born in 1968, in the midst of the Apollo missions to the Moon. His grandparents worked in the Lancashire cotton mills but his middle-class parents, who worked in a bank, managed to save up enough to send him to Oldham's Hulme Grammar School. He showed all the signs of being a nerdy boy until hormones kicked and he discovered girls, rock music and how to replicate the electropop of Kraftwerk and Ultravox using a box wired up to a high-hat cymbal.

He has a young son with his American-born wife of seven years, television presenter Gia Milinovich, who has by now has got used to the idea that her husband is famous. Gia remembers the first day a paparazzo ran backwards taking snaps of them as they took a stroll with their new baby. "Pre-fame, I was asked for my opinions. Now, I'm asked what Brian thinks," she says.

Last Thursday, Cox's 43rd birthday, the couple went to see Danny Boyle's Frankenstein at the National Theatre in London. Cox had been the scientific consultant on Boyle's 2007 film Sunshine, a science-fiction drama about a mission to the dying sun. He says that he enjoyed the play immensely, not least because of Mary Shelley's obvious fascination with science when she wrote her 1817 novel about a modern Prometheus.

Cox doesn't believe that Frankenstein has given science a bad name. "It's too simplistic to say that Frankenstein is a story about the dangers of meddling with nature," he says. "Mary Shelley was actually a big fan of science."

Cox, an avowed atheist, says he is rather relaxed about religion. He has even become good friends with the Dean of Guildford Cathedral after he took the cleric on a tour around the Cern laboratory. He has also been invited to the house of the Archbishop of Canterbury, a fan of his first television series. Rowan Williams is "a very thoughtful man", Cox says.

Science charlatans, homeopaths and people who believe in the Mayan prediction that the Earth will end in 2012 do not get so much of his sympathy, however. "People who believe that the world is going to end in 2012 are twats," he says.

Cox nevertheless believes that the forces of anti-science need to be tackled head on. "I think one of the great challenges for the scientific community is how to deal with arguments from people with genuinely held views that are demonstrably wrong and potentially damaging," he says.

Which is one of the reason why he is taking his role as science communicator so seriously. He says he will always remain an academic grounded in university research, but he will also exploit his new-found popularity as a media star to thrust science and scientist into the wider political arena. "I do have an agenda," he says. "I believe that Britain needs to be a more scientific nation. I'm happy to be one of the most high-profile scientists in the country, and I feel a responsibility to use that appropriately."

After all, there are not many professors of physics who can boast a science column in The Sun.

'Wonders of the Universe', BBC2, Sunday, 9.00pm

A life in brief

Born: 3 March 1968, Oldham, Lancashire.

Family: The son of bank workers, he married TV presenter Gia Milinovich in 2004; they have one child together.

Education: Hulme Grammar School in Oldham. First-class degree in physics from University of Manchester and PhD in high energy particle physics.

Career: Juggled studies with a stint as keyboard player for the bands Dare and D:Ream. Received an OBE and was granted a Royal Society University Research Fellowship in 2005. He was professor of particle physics at Manchester and working on the Large Hadron Collider at Cern when he was asked to be a presenter. Last year's Wonders of the Solar System on BBC2 has been credited with reinvigorating the public's interest in science. His new series, Wonders of the Universe, starts tomorrow.

He says: "To many people, science looks like an old man's game, but it isn't. Most of the science in this country is done by people in their twenties."

They say: "The best programme I've ever seen." Chris Evans on Wonders of the Solar System

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks