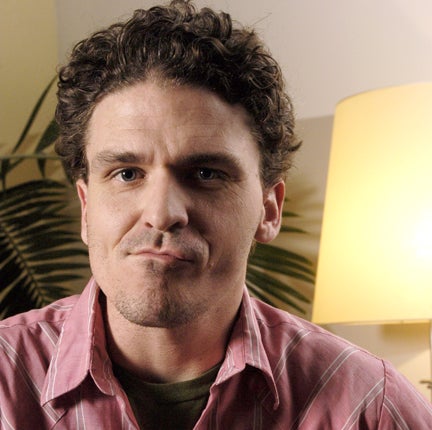

Dave Eggers: My generation

The American novelist champions irony and lost causes. Now cinemas are yielding to his curious view of the world. What makes him tick?

Let us begin with a wise, witty, rather foxy and extremely artful intro. Come on, make an effort. We are not dealing today with someone who will offer you everything on a pre-postmodernist plate. This is about Dave Eggers, the voice of Generation X, the most influential man in contemporary American literary circles, and all the rest.

But before you dismiss Eggers as another Daedalean clever clogs with a impossibly long list of list of facile, self-referential, sarcastic and ever so coooooool achievements to his credit, take a look at this website

Bear with it past the first five or six minutes. This man may look like a flake. And his cultish autobiographical memoir A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius may be too clever by three-quarters with its hip self-deprecation and too-chic-to-be-comprehensible language games. Eggers is a force of nature, so sit up and take notice. But he can tell stories too – when he wants to – and plain, compelling and magical ones at that. Screenplays for Sam Mendes' Away We Go, co-written with his wife and released last month,and Spike Jonze's next film, out in October, are pricking Hollywood ears. So let us turn him into a story and shape some patterns of meaning out of the chaos of his hyper-sophistication.

Eggers burst upon fashionable literary consciousness barely nine years ago with the publication of his Heartbreaking memoir. In the US, the book was a huge critical and then commercial success. It reached No 1 in The New York Times bestseller list in 2000 and was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize. Time magazine named it Best Book of the Year. It told the story of how, when Eggers was 21, both his parents died within a year, his mother from stomach cancer and his father from brain and lung cancer.

At the time Eggers was doing a degree in journalism at the University of Illinois, but he packed it in to look after his younger brother, Toph, who was only eight. In and out of the years that followed, Eggers became a jobbing journalist, writing for the online magazine salon.com, and others, to earn enough to support his brother. Eggers moved to San Francisco and wrote a comic strip for SF Weekly. To exercise his unsatisfied undergraduate creativity he launched a satirical magazine called Might, which, as it turned out, did not.

But every night in Eggers' room a forest grew and grew as he penned the lightly fictionalised tender story of his desperate love for his little brother after the death of their parents. He called it, with his heavy sense of almost-irony, A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius. "I thought only a few people would ever read it and the publishers really thought they'd lose money on it," he said later, with engaging modesty – or was it retrospective realism? But it became a cult hit which one critic called "a dazzling, high-wire act of a book from a stunningly talented new writer".

His was the voice of a new generation – with a laid-back superficial cynicism and idiosyncratic style beneath which lay the unchanging ever-hopeful American Dream. It revalidated old values with cool postmodern digressions: "The first three or four chapters are all some of you might want to bother with. That gets you to page 123 or so, which is a nice novella sort of length." It told hokey homey truths but with modish self-awareness: "Ooh, look at me, I'm Dave, I'm writing a book! With all my thoughts in it. La la la!"

More novels followed, inevitably. But so did much more. Eggers had already founded a magazine called Timothy McSweeney's Quarterly Concern which, being a literary quarterly, came out two or three times a year. Next came a publishing house; then a monthly magazine, The Believer, edited by Eggers' wife, Vendela Vida; and then a quarterly DVD magazine, Wholphin. All shared the same modish manner disguising a relentless optimism.

It all brought him an unexpected fame. But, as the San Francisco Chronicle noted, "Dave Eggers treats his celebrity like a gold lamé suit. It's amusing, absurd and, in his mind, not quite appropriate." Even so, he put it to good use. Eggers has worn his suit to make trouble of one kind or another all over the literary world. Among his many enterprises he edits, along with The Simpsons's creator Matt Groening, an annual anthology of short stories and essays called The Best American Non-Required Reading which has become the very opposite of what its title suggests.

Eggers is America's new literary style guru. It is he who determines who are the fashionable up-and-coming writers. The corporate publishing giants who once rolled their terrible eyes and showed their terrible claws have been tamed by Eggers' magic realism trick of staring into their yellow-press eyes without blinking. They have made him king of all wild things and begun publishing the writers from the literary vanguard whose membership Eggers has defined. The wild rumpus has begun.

Many of Eggers' friends are teachers. Over the years he has been affected by their stories of how a child's life can be transformed by individual attention. But teachers don't have enough time to give all their pupils that. Eggers thought of all the lonely writers that he knew who yearned for human contact. So he set up a centre called 826 Valencia, named after its postal address, as a place where writers could meet kids aged six to 18 and tutor them. Within a few years it has spread out to Los Angeles, New York, Seattle, Chicago, Michigan, Boston and now Dublin. Last year the writer won the prestigious TED Prize for the work and earned Eggers the accolade as "the Bono of lit".

Like Bono there is the same odd mix of activist, artist and businessman about Eggers. In 2003 he set up an oral history programme called Voice of Witness to allow survivors of human-rights abuses around the world to tell their stories. In 2005 he published a book of interviews with former prisoners sentenced to death and later reprieved.

His sense of mission has led Eggers to blur boundaries between advocacy, documentary and fiction in his work. His walls became the world all round. His 2006 novel What Is The What told the true story of a seven-year-old boy forced to leave his village in Sudan – pursued by militias, government bombers and lions which ate three of his fellow refugees – and trek hundreds of miles by foot across the desert. Eggers gave it a vivid sense of place but imbued it with a universality about a boy coming of age. "It is impossible to read this book and not be humbled, enlightened, transformed," said the author of The Kite Runner, Khaled Hosseini.

Eggers' most recent novel Zeitoun, published this year, is another true story. It is about a Syrian immigrant turned New Orleans contractor and landlord, who stayed in the city after Hurricane Katrina to protect his properties. Ferrying between them by canoe he rescued and fed neighbours for days. But then he was arrested, inside one of his own properties, under suspicion of being a terrorist.

The novel brings together the archetypal absurdities of the Bush era, the "war on terror" and the Katrina debacle, to tell a simple story, but one laced with political significance.

Unhip as it may be in the me-me-me nihilism of Generation X, Eggers wants to make the world a better place – or at least more like the nice parts of San Francisco. It is an approach which polarises critics, not least on the screenplay he co-wrote with his wife for Mendes's Away We Go. It is about an idealistic couple travelling across North America to find the perfect place to raise their family. "An exercise in self-righteous, progressive banality," one critic pronounced; "if their characters find they are superior to many people, well, maybe they are," contradicted another.

Eggers' next offering is the screenplay of Spike Jonze's movie of the Maurice Sendak classic children's book Where the Wild Things Are, which is to be released in October. The story is about fear but also about hope. But then Dave Eggers has always wanted to end up where someone loved him best of all, even if he would not like you to deconstruct it so plainly.

A life in brief

Born: Boston, Massachusetts, 12 March 1970. One of four siblings; his father was an lawyer and his mother a teacher.

Early life: Eggers grew up largely in Lake Forest, a suburb of Chicago. He attended the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, with a view to getting a journalism degree. When he was 21 his mother died of stomach cancer and his father died of brain and lung cancer, Eggers moved to California with his girlfriend and eight-year-old brother.

Career: Wrote acclaimed memoir A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius while working for Salon.com and co-founding Might Magazine. The book was a bestseller and Pulitzer Prize finalist. He has written several books since, including You Shall Know Our Velocity (2002), How We Are Hungry (2004), and What Is the What (2006). He founded the independent publisher McSweeney's and literary magazine The Believer, which is edited by his wife, Vendela Vida.

He says: "We have advantages. We have a cushion to fall back on. This is abundance. A luxury of place and time. Something rare and wonderful. It's almost historically unprecedented. We must do extraordinary things. We have to. It would be absurd not to."

They say: "It would be a mistake to think Dave Eggers has given up irony. What he has done is to send it deep into the text where it can do its own work." M John Harrison, reviewing What Is the What in the Times Literary Supplement

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks