David Bellamy: 'I was shunned. They didn't want to hear'

The botanist, 80 this week, says the end of his TV career was caused by his views on climate change. Paul Cahalan meets David Bellamy

They share a name – David – and a passion for nature. For a while they also shared a place in the vanguard of nature documentary-making, broadcasting from every corner of the globe to the homes of millions. But while one, Attenborough, basks in the glow of national treasure status, the other claims he is now a pariah.

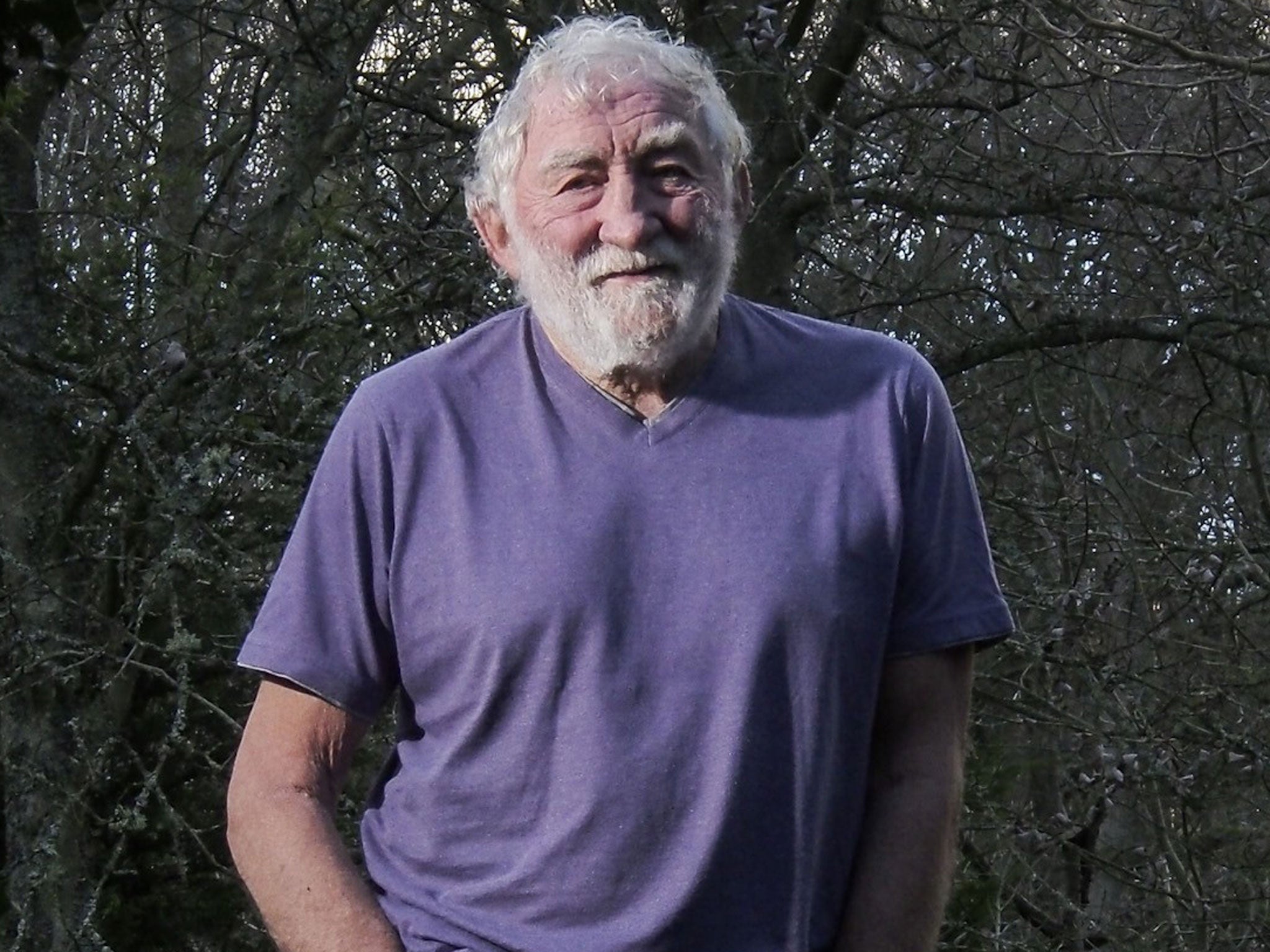

"You're early," David Bellamy roars, dropping the wheelbarrow he is pushing around his four-acre garden in Co Durham. He strides towards me, all rolling gait, unruly white hair and beard. "Go inside while I just finish off."

Though he turns 80 next Friday, Bellamy has a remarkable physique for a man his age, over 6ft tall and slender, muscular even, despite a little trouble when he walks. The voice and appearance have stayed in pretty good nick since his heyday as a scientist, conservationist and TV personality. He was a household name, inspiring Lenny Henry's "grapple me grapenuts" catchphrase and even a Ribena commercial.

But for the grace of God he would be revered as the man who brought botany to life through glorious rambling monologues in a time before CGI graphics and hi-tech film techniques became de rigueur. But his fame and acclaim rolled off the rails in 2004 when – in the teeth of public opinion and mounting scientific evidence – he said global warming was nothing but "poppycock". He was deserted by fans, shunned by peers and, he says, ostracised by broadcasters and conservation groups that once thrived through his endorsement: he was sacked as president of the Wildlife Trusts.

Bellamy, who appears not to be able to shake the habit of speaking as if the camera were still rolling, is unrepentant. He is clear his stance on climate change ended his TV career. Some point out that an ill-fated dip into politics before this, standing against the then Prime Minister John Major in Huntingdon in the 1997 general election for the Referendum Party, cannot have helped.

Nevertheless, in a flurry of rapid hand gestures, gravelly voice – oscillating between whisper and oratory – through the filter of that full beard, he is unequivocal. "All of the work dried up after that. I was due to start another series with the BBC but that didn't go anywhere, and the other side [ITV] didn't want to know. I was shunned. They didn't want to hear the other side." But does he still believe he is right? "Absolutely. It is not happening at all, but if you get the idea that people's children will die because of CO2 they fall for it," he says, perhaps buoyed by forecasters at the Met Office this week downgrading a prediction for global warming to suggest that by 2017 average temperatures will have remained about the same for two decades.

"Someone even emailed me [at the time] to say I was the worst paedophile in the world, basically saying I was killing children by denying global warming," he continues, "but in the last 30 years crops have got greener and grow quicker." CO2 acts as a fertiliser, he tells me, "and that is good news but we don't get". He can't resist dragging his namesake into things, saying David Attenborough "was on our side [denying climate change] at first but then he had a change of heart".

But, I ask, what if you are wrong? "Then I'm wrong. But I'm not."

Born in London and raised in Sutton, Bellamy says life as a boy during the Second World War taught him "to fight for things". By the time he was 14, he was a brawny 14 stone grammar school rugby fan, but with a fondness for ballet which endures. After work in a factory and as a plumber, at the age of 19 he met Rosemary – to whom he is still married – and won a place at Durham University, where he studied and later taught botany.

He claims good fortune played a part in his becoming the nation's best-known botanist. "I was lucky," he says too modestly. He worked on a project in Cornwall after the Torrey Canyon oil disaster off the British coast in 1967. It was published and led to his first interview where the distinctive voice and obvious intellect, together with an unmistakable screen presence, prompted the first TV offers. They turned into 20 years of relentless filming. There was little problem with being away from his family: he simply took them with him.

Is he sad no longer to be on TV? "No, I had made things about which I knew. I had pretty much run out of those. And TV has changed, with gadgets and all that," he adds, mentioning that other David. "Now he has people sitting there for six months to get one shot. But you can't knock him. He has opened the eyes of millions of people."

TV money allowed him to indulge whims – a foray into pop, comics, books and that shot at being an MP, for example. Nevertheless, he admits that the advancing years have started to take their toll. One obvious sign is forgetfulness which, by his admission, grows worse. Another is a new hearing aid, which causes him to cock his head wildly and bellow "ask me again", though it has the benefit of allowing him to hear more birdsong.

His career would not have been be possible without Rosemary, his "pillar", who is never far from his side during the interview and often finishes his sentences. She beckons us for a cup of tea and some nibbles into a kitchen that has the ordered chaos of a busy household, family photos competing with royal mugs and porcelain. The couple have five children – four adopted: Rosemary had five miscarriages, "which was a tough time", Bellamy says.

Since his TV work dwindled, Bellamy channelled the anger over his enforced hiatus into campaigning, which first stirred in him after a trip to Sierra Leone. "I met a local boy called Bodcco. He was nine and could point out more of the local plants than I. He was fantastic," he says. "One day he didn't turn up. When I asked why, they told me he had died from malnutrition. He died because we [humans] had gone in there and dug up the diamonds and chopped down the habitat."

In truth, he has always been ready to get stuck in for the environment. He was jailed during a campaign against a proposed dam in Australia in 1983, and, as well as starting charities, Bellamy was patron of more than 400 organisations at one time. "I helped start conservation. There were no groups when I was first around," he says. "Now they don't want to be anywhere near me. The WWF has saved a few pandas – but where are they with the forests? What are the groups doing? What we have lost is our common sense."

His relationship with the environmental lobby remains ambivalent: outspoken attacks such as the above did not ingratiate him, and nor did his dislike of wind turbines.

But is he happy? "I have been very lucky. I have a beautiful wife and family. I didn't think I would ever do it but I did and it got thrust on me."

How does he view his work? "I don't know. People still know me but now they say, 'David Bellamy? I thought you were dead'."

Curriculum vitae

1933 Born on 18 January in London, David James Bellamy is raised in Sutton and educated at Sutton County Grammar School. After leaving school he works in a laboratory at a technical college in Ewell before winning a place at Durham University, where he studies botany.

1959 Marries Rosemary Froy. The couple have one child and adopt another four.

1967 Comes to public prominence as an environmental consultant during the Torrey Canyon disaster. Makes TV appearances after publishing report on the disaster.

1970 Life in Our Sea on the BBC is the first of Bellamy's major TV shows.

1972 Writes Bellamy on Botany, the first of his more than 40 books.

1978 Receives Bafta's Richard Dimbleby Award for Outstanding Personal Contribution to Factual Television.

1982 Launches the Conservation Foundation with David Shreeve, aiming to help collaboration in environmental work.

1983 Jailed for blockading the Australian Franklin River in a protest against a dam.

1992 Questions the science behind climate change at an intergovernmental policy committee meeting.

1996 Speaks out against wind farms.

1997 Stands against John Major for the anti-European Referendum Party.

2002 Autobiography Jolly Green Giant.

2004 Again attacks climate change, calling it "poppycock".

2005 The Royal Society of Wildlife Trusts ousts him as president.

2010 Stars in an advert for an insurance company with a dog puppet.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments