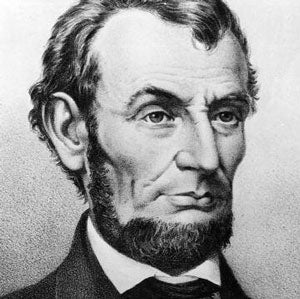

Abraham Lincoln

16th president - 1861-1865

The genius of Abraham Lincoln is such that almost all American presidents and presidential aspirants since have turned to him for guidance and inspiration. Theodore Roosevelt hung a portrait of Lincoln above the fireplace of his White House office, saying that he wanted "so far as one who is not a great man can model himself upon one who was" to do "what Lincoln would have done". Franklin D Roosevelt considered Lincoln to be the ultimate political operator and sought to emulate his deeds. Harry Truman, a Democrat with strong connections to the Confederacy and who consequently would never easily identify with a Republican president, admired the fact that Lincoln had had the strength of character to follow his instincts and, in the face of strong opposition, do what he thought was right.

There are other noteworthy examples. A few days after his nomination for the presidency in 1952, Adlai Stevenson, a man who had always been inclined to the loftiest political ideals, left the Illinois governor's mansion in Springfield and walked to Lincoln's old home just after midnight to sit in the famous Lincoln rocking chair for nearly an hour. The American magazine Newsweek recently recalled Stevenson saying that, once he had done that, he felt a "deep calm" about the possibility of taking on the enormous burden of being President of the United States. The great communicator himself, Ronald Reagan, whose speeches were so well crafted by his writers and then so brilliantly delivered, invoked Lincoln's name several times to describe his new vision for America. Even Richard Nixon found it useful to quote a few lines from a Lincoln speech, although they were deployed in a rather self-serving, and ultimately perverse, attempt to justify his role in the Watergate scandal.

But none of these comes as close to President-elect Barack Obama's respect for Lincoln as perhaps one of the most extraordinary individuals in American history, and certainly one of the greatest presidents. Asked on American television about the book he would consider required reading in the Oval office, the senator from Illinois chose Team of Rivals, Doris Kearns Goodwin's magisterial biography in which she describes Lincoln's political ascent from humble beginnings to a presidency marked by such uncommon magnanimity that it allowed him to embrace his enemies and invite them into his cabinet; people against whom he fought the fiercest political battles and who all wanted to be president. In his book The Audacity of Hope, Obama recalls that he once wrote an article for Time Magazine in which he said: "In Lincoln's rise from poverty, his ultimate mastery of language and law, his capacity to overcome personal loss and remain determined in the face of repeated defeat – in all this, he reminded me just... of my own struggles."

Obama may have been guilty of going too far in comparing himself to Lincoln, but few would disagree that in the way he conducted his recent campaign, in his speeches and in his recent political appointments he has tried to reach out, as Lincoln did, beyond the comfort lines of his own party. In one memorable passage of the speech he delivered to the Democratic convention years before he was even thought of as a possible presidential candidate, Obama appealed to his audience in the hall and to Americans everywhere, to act and to think beyond mere party affiliations, and to regard themselves not as being a part of blue states or red states, but as being part of the United States of America. Lincoln would have approved. That was essentially the theme of his political life, and is one to which Obama has returned time and time again.

So why has Lincoln attracted such unbounded admiration over so many years? At a time of the greatest crisis in the life of his country, he was blessed with the political skill and good sense to forge a team of the best available talents that preserved a fledgling nation and freed America from the scourge of slavery. And he did it with diligence, magnanimity, honesty and integrity. His abiding faith in politics as an instrument to improve the lives of all citizens is still inspiring today and ennobles the concept of democracy.

Lincoln came from no established political class. He was born in a log cabin on an isolated farm in rural Kentucky on 12 February 1809. So aware was he of the poverty all around him that throughout his life he would describe his childhood to any questioner by simply reciting a line from Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard by Thomas Gray: "The short and simple annals of the poor."

Young Abe was a boy who loved books. In a culture that rated manual labour more than intellectual pursuits, it was fortunate that he was allowed to spend so much time reading, which he was encouraged to do by his doting stepmother. His father was much less tolerant. Reading on his own and solidly for long hours, shutting out all contrarian noises, he developed great powers of concentration and a phenomenal memory.

Lincoln reached manhood at a fascinating time in the life of the emerging American nation. For the first time, people began to feel good about their prospects for a better life. It was indeed morning in America. They saw their country as a land of opportunity for all, not just the fortunate few. The American Revolution had removed almost every barrier to success. It was perhaps the birth of the feeling that everything was possible. Both the privileges and disqualifications of class were rapidly disappearing and men had broken through "the bonds which once held them immobile". The French visitor Alexis de Tocqueville was so impressed by what he saw that he was moved to write that "the idea of progress comes naturally into each man's mind; the desire to rise swells in every heart at once and all men want to quit the former social position". Ambition, he observed had become a "universal feeling". As if to emphasise the point, the Frenchman went on to say, as Doris Kearns Goodwin relates in her Lincoln biography, that every American "is eaten up with longing to rise".

What a powerful sentiment that was and what a great time to be alive. Young men such as Lincoln and those with whom he would eventually compete for high office, William Henry Seward, Salmon Chase and Edward Bates, accurately judged the mood and reacted to the temper of their times by deciding to devote their talents to public service. This was almost certainly due to the fact that Americans had fought for and won the right to govern themselves and thousands of young men, seeing a career in politics as a vindication of their struggle for self-determination, were bursting to throw their hats into the ring.

It must be said though that many did this, not in the interest of serving the public, but as a means of personal advancement. But that was not necessarily considered a disgrace. Upward mobility, however it was achieved, was no bad thing. Newspapers were becoming more popular, and people anxiously sought them out to inform themselves about the newest trends. Politics was in vogue. It was the big game in town and participation was the thing. The ability to speak well and by oratorical brilliance to command the attention of the listening crowds was considered one of the finest arts. Voters turned out in record numbers in state and national elections.

Just past the age of 20, the bookish Lincoln left his family home in the country and headed for the budding town of New Salem, Illinois to devote his time to studying law. He attacked his legal studies with the same single-minded dedication and passion he reserved for reading and spent many hours trying to make up for the early learning he felt he lacked. As a practising lawyer in the courts he was admired by his fellow professionals and regarded by everyone who met him with great affection. He had been in New Salem for a few months when, at the age of 23, he decided to try to win a seat in the state legislature. It was an ambitious move and Lincoln knew it. He was largely unknown and he did nothing to hide his humble origins. His speeches on the campaign trail, as they would be all his life, were spiced with self-deprecating humour and a fund of anecdotes that had earned him a growing circle of friends and supporters.

Lincoln's inexperience proved to be too big a handicap and he lost. But even in that failed campaign, he demonstrated some of the qualities that would serve him well in his later life as a senator and as the President. He spoke the truth as he saw it. He was almost never pompous or too arrogant to admit that he might be wrong. He tried to understand the position taken by others. He was a man of integrity and high principle. Those virtues would be important to him, because when he did get to the state legislature a few years later, he would face the issue that defined his career in politics and sparked a period of unequalled turbulence in the country.

The issue of slavery would in various ways follow Lincoln to his death. Slavery was legal in Lincoln's home state, Kentucky, but his parents were against it. Their conviction had caused them such social and religious discomfort that they were forced to move, but that was as nothing compared with the trouble it was about to cause the young state legislator Abraham Lincoln. Moves to abolish slavery in the northern states led legislatures across the country to debate the right to keep slaves. When it came up for discussion in Illinois, the assembly voted by an overwhelming majority of 77 to six to defend the "right of property in slaves".

Lincoln was one of the dissenting voices and he had nailed his colours to the mast. He explained later that he had never wavered from the belief that if slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong. He never did change that view in the years that followed. What is interesting is that, in many respects, Lincoln's position on slavery was what would be called, in the world of politics today, very finely nuanced. For a long time, he found it difficult to convince the abolitionists that he was on their side. He believed that enslaving people was fundamentally wrong and should come to an end, but he repeatedly made it clear he did not believe Congress had the power to interfere with the practice in states where it was already established. And right up to the time he arrived in Washington in 1847 as a congressman from Illinois, he felt slavery was such a bad practice that it would eventually wither on the vine and die of natural causes. Many other politicians felt the same way, but they, as with Lincoln, were ignoring the economic reality.

The American south had quickly been transformed into a vast and prosperous cotton empire trading with the world. The Industrial Revolution in Britain had opened up a seemingly unending demand for American cotton and very soon it accounted for no less than 57 per cent of all American exports. Central to this success were the industry's four million slaves.

This was not the kind of prosperity the south would ever willingly give up, and when Lincoln began his run for the Senate in 1858, he was forced to acknowledge the dangers the slavery issue posed to the very existence of the Union. The time had come for him to make a more emphatic statement about slavery and the way in which it threatened to tear the country apart. Quoting from the Gospels and referring to the North-South polarisation of opinion on the issue, he said: "A house divided against itself cannot stand." Further, to state his intentions in a way that could not be misinterpreted, he said plainly: "I believe this government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free."

He was applauded in the North but castigated as an enemy of the slave-owning South. As Doris Kearns Godwin wrote, it set the stage for "a titanic battle, arguably the most famous Senate fight in American history, a clash that would make Lincoln a much better known figure and propel him to the presidency". Lincoln's opponent was Stephen Douglas, a Democrat who knew how to woo an audience and debunk the claims of his opponent. He went straight for the jugular. He attacked Lincoln as a "Negro-loving agitator bent on debasing white society". And when in his public speeches he asked voters whether they would entrust their government to a man who wanted black people to serve on juries and to be eligible for high office, he got just the response he expected – they shouted, "Never!"

Douglas's face-to-face debates with Lincoln energised the electorate as never before. People turned up in their thousands to hear their encounters which, unlike their pale imitations in our own century, frequently lasted for hours. But the race and the campaign had so captured the public's interest that everyone who came to listen to the candidates stayed to the end, frequently interjecting their own comments and observations as the two protagonists slugged it out. Newspapers lapped it up; reports of the debates circulated around the country and one observer described the verbal gymnastics of the candidates like watching two prize fighters locked in deadly combat. In the end, Lincoln was forced to respond to his opponent's jibes by saying that he had never suggested "political and social equality between the white and black races" nor suggested that they should be able to vote, sit on juries or be allowed to intermarry. Douglas had put him on the defensive. Lincoln picked up some support when he urged voters to look beyond the present and to remember the essential message of the Declaration of Independence that "all men are created equal", but he had failed to take the sting out of his opponents' attacks and lost that race for a seat in the Senate. Not the kind to brood too long over failures, he was disappointed but not downcast. He was determined to find himself a role in the political life of his country and only two years later he found himself in an even bigger battle, this time to be the Republican party's nominee for president, competing against his old rivals, Seward, Chase and Bates.

The Republican convention in Chicago was the political event of the decade. Party representatives from all over the country poured in to be part of the event. There was palpable excitement over the possible outcome of the party's deliberations and when the convention doors opened, people who had been waiting for hours swarmed in. In no time at all every seat had been taken by the 10,000 delegates. Seward's chances of clinching the nomination seemed good and, after intense discussions on a series of procedural matters, he duly emerged as the firm favourite. His supporters thought he was so comfortably ahead that at one point very early in the proceedings they were preparing victory celebrations. Seward had immersed himself in politics, cultivated a number of influential friendships, and had never lacked self-confidence. He had also carefully prepared the ground before making his bid for the nomination by travelling widely in America and in Europe, where he had been accorded the honour of audiences with Queen Victoria, the kings of Belgium and Italy, and Pope Pius IX, and meetings with Lord Palmerston and William Gladstone. To have met such an impressive list of the great and the good would represent quite an achievement for any American politician in any age, and it was seen as a boost to Seward's chances. And although some colleagues said he had shown bad judgement in spending so much time grandstanding outside the country, among people who had no votes, he remained the candidate of stature at home and abroad.

But political gatherings are unpredictable; they have a way of turning conventional wisdom on its head, and strong doubts emerged about the number of states Seward could carry for the party in a general election. Bates was then considered as the possible nominee, but his national popularity was also questioned. All hopes that Chase had of getting the nomination died, because his campaign team were unable to cope with the ferocious political infighting that swirled around the choice of a nominee. With those three fading in the home straight, thoughts turned to another candidate – when one delegate moved to propose the name Abraham Lincoln, 5,000 people jumped to their feet in noisy acclamation. More soundings were taken and there was more balloting of the delegates.

As tension mounted, the move to nominate Lincoln gathered momentum. Seward's people fought on. Chase and Bates continued to push their agendas, but across the convention there was a call for unity to give Lincoln a unanimous victory. And so to the consternation of the other candidates the deed was done. The convention hall and the city of Chicago erupted into wild celebration. Seward was distraught and badly shaken by his party's failure to choose him. For many months, Chase reflected on how close he had come and couldn't quite come to terms with how he had failed to clinch it. Bates accepted the outcome with frustrated resignation. All were terribly disappointed.

A journalist at the time described how the surprise choice, Lincoln, was surrounded by throngs of joyful well-wishers. They filled the streets, converging on his house, and church bells tolled. The candidate received their congratulations with typical modesty, saying that it had been a victory not so much for him but for the party. Perhaps even at this early stage, Lincoln realised that his nomination would have far-reaching consequences. He knew his well-known anti-slavery reputation meant that the prosperous slave owning south would always be implacably hostile to his election, and he was right. Slavery was still the issue dividing the country, but there were others about which Lincoln had said little in his fight for the nomination, and consequently there were questions about his suitability to be a president.

Some commentators at the time concluded that the Republicans had simply made a bad choice. They felt that in comparison with men like Seward and Chase, Lincoln was a political pygmy, a backwoodsman, still largely unknown, and a speaker who tried to conceal his inadequacies by telling homespun stories. Others bluntly expressed the view that Lincoln was rather boring. It was even noted waspishly that he was very spare in his personal habits, not very convivial and never smoked tobacco or drank. The presidential election was close. The Republicans won, but without the decisive mandate they had sought. Lincoln got less than a majority of the popular votes but achieved a solid majority in the Electoral College.

The President-elect immediately set about selecting his team for government, and in an extraordinary gesture of magnanimity the first names on his list were, Seward, Bates and Chase, the very men he had only recently fought and defeated in the nomination process. William Henry Seward, perhaps Lincoln's fiercest opponent, was persuaded to become Secretary of State. Chase was given the top job at the treasury and Bates was asked to become Attorney General. Lincoln's decision to bring them into his government was a shock even to his associates. One of them remarked that it was possible to offer a job to one of his former opponents, but to offer jobs to all three was insane. And in Team of Rivals, Doris Kearns Goodwin relates that President Lincoln was closely questioned by a journalist about his philosophy of choosing to give jobs to men who had been his sworn political enemies, men who were still smarting at losing to him and who in all probability still harboured the belief that they were much better qualified to be President than he was. His reply is sage advice to any political leader or head of state.

Lincoln said: "We needed the strongest men of the party in the cabinet. We needed to hold our own people together. I looked the party over and concluded that these were the very strongest men. Then I had no right to deprive the country of their services." This was in many ways the very essence of Lincoln's approach. All his life he'd wanted to feel worthy of the positions in which he found himself, but he also wanted to make sure that all his actions were based not on political expediency but on principled belief. The soubriquet "Honest Abe" was sometimes employed by Lincoln's detractors as a term of derision, but the man himself would never have thought it so.

One month before the new President was formally adopted into office, the storm clouds that had been gathering over the new administration burst open. Seven states, later to be joined by four others, seceded from the Union and declared the creation of a new nation, the Confederate States of America. Mr Lincoln's house was now truly and dangerously divided. One of the many historians of the period has suggested that the tragedy of the Civil War that followed was that neither North nor South realised until it was too late that the other side was not bluffing and was desperately in earnest. It is interesting, as Roger Osborne points out in his book Civilisation, that in his inaugural address, Lincoln never promised to outlaw slavery and even offered to make the right to own slaves part of the constitution – but he was against any extension of slavery or secession from the Union. And so he promised at his inauguration to do everything in his power to "hold, occupy and possess" the property and places belonging to the Federal government that lay in Confederate territory. It is almost certain that what he had in mind was Fort Sumter, a stronghold on an island near the mouth of Charleston Harbour in South Carolina.

The building flew a United States flag, a source of great offence to South Carolina and the Confederacy. Southerners appealed to the White House to take the flag down and leave the fort; to show that they meant business they surrounded the harbour with troops and guns. Lincoln responded by saying that he would send supplies to the beleaguered stronghold. That was taken, quite rightly, to mean that the President had no intention of giving up Fort Sumter. The die was cast. The Confederate commander General PGT Beauregard was given the order to turn his guns on the place. The bombardment went on for 30 hours. With supplies running low and with few options left, the Union officer hauled down the flag, ordered his men to leave and turned the fort over to the Confederacy.

No one died from the shots fired at Fort Sumter, but the Civil War had begun. The conflict was a profound tragedy for Lincoln's America. It claimed the lives of more than 700,000 people and devastated large parts of the country. The Union and Confederate armies had fought to a standstill and there was national relief when, after four years of bitter fighting and unconscionable brutality, General Robert E Lee bowed to the inevitable and, to avoid more pointless slaughter, surrendered to Lieutenant General Ulysses S Grant at Appomattox in Virginia in April 1865. The war was over, but it left a legacy of rancour and mistrust that would course its way through the veins of American politics and life for generations. Arguments about slavery did not directly start the conflict, but slavery was the issue around which all the disagreements between the North and South converged.

One highlight is the effect of the war on slavery. At great risk, slaves in the Confederacy deserted their plantations to join the Union armies. By the end of the war there were more than 180,000 black soldiers fighting in 166 Union regiments. Emancipation was becoming a reality. Three years before, in 1862, Lincoln and his cabinet declared slavery to be illegal and all slaves free. One year later, dedicating a part of the Gettysburg battlefield as a final resting place for fallen Union troops, he made the speech for which he is famous, reminding his countrymen: "Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in Liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal." The battle for true equality for all men in America went on for many years after Lincoln's tragic assassination by the mentally unbalanced John Wilkes Booth on 14 April 1865. As recently as March 1965, millions of black Americans in 11 southern states were still unable to vote. When they tried to register they were confronted by a number of humiliatingly frivolous questions to "test" their literacy, the most infamous of which was "how many bubbles are there in a bar of soap?" When they couldn't answer, they couldn't vote. Later that same year, President Lyndon Johnson drove past a crowd of demonstrators and went up to Capitol Hill to urge Congress to pass the Voting Rights Act.

The Civil Rights march from Selma to Alabama had taken place only a few months before and Johnson adopted the anthem of the marchers' movement as his own. He said: "Even if we pass this bill the battle will not be over. What happened in Selma is part of a larger movement that reaches into every section and state of America. It is the effort of American Negroes to secure for themselves the full blessings of American life." The President continued: "Their cause must be our cause... because it is all of us who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice." Johnson paused and concluded that speech to Congress with the words: "And we shall overcome."

Lyndon Johnson's biographer, Robert Caro, has written that while Lincoln cast off the chains of black Americans, it was Lyndon Johnson who led them into the voting booths, "closed democracy's sacred curtain behind them and placed their hands on the lever that gave them a hold on their own destiny." It is that hold of their destiny that began with Lincoln and continued with Johnson that let Barack Obama, a black American, to be nominated by his party and to fight and win the election to become the 44th President of the United States. The new President will almost certainly invoke the memory of Lincoln's life and career at his inauguration. A few days before the election on 4 November last year, when their private polls convinced the Democrats they would defeat John McCain, word reached his speechwriter that Senator Obama wanted to "lean into bipartisanship a little more. Even though the Democrats have won a great victory, we should reach out and be humbled by it. Figure out a good Lincoln quote and bring it all together. Take a look at Lincoln's first inaugural address". The speechwriter duly obliged and came up with the line in which Lincoln appealed to "the better angels of our nature". At his speech in Chicago on the night of his victory, Obama used Lincoln's words to great effect: "We are not enemies, but friends. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection."

At the stroke of midnight on New Year's Eve members of many black churches in America concluded their ritual "watch night", a traditional prayer service that took on new meaning for African-Americans in 1862, on the eve of the enactment of Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation. This time the churches gave thanks too for the election of an African-American President who will be inaugurated a few weeks before the 200th anniversary of Lincoln's birth.

In his own words

"With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation's wounds..." (From his second inaugural address)

"Whenever I hear anyone arguing for slavery [to be allowed to continue], I feel a strong impulse to see it tried on him personally."

"You can fool some of the people all of the time, and all of the people some of the time, but you can't fool all of the people all of the time."

The gettysburg address

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate — we cannot consecrate — we cannot hallow — this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us — that from these honoured dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Delivered at the dedication of the Soldiers National Cemetery at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, on 19 November, 1863.

In others' words

"He was not born a king of men... but a child of the people, who made himself a great persuader, therefore a leader, by dint of firm resolve, patient effort and dogged perseverance." Horace Greeley

"The president is nothing more than a well-meaning baboon. He is the original gorilla. What a specimen to be at the head of our affairs now!" General George B McClellan

Minutiae

Lincoln was famously ugly, and self-deprecating. Accused in a debate with Stephen Douglas of being two-faced, he replied: "If I had another face, do you think I would wear this one?

Lincoln's son, Robert Todd Lincoln, was in the vicinity when his father was assassinated. He went on to witness the assassinations of two other presidents: Garfield, and McKinley.

In the weeks following Lincoln's assassination, $22,000 worth of presidential china was stolen from the White House by souvenir-hunters.

Lincoln oversaw the largest mass hanging in US history: of 38 Sioux Indians in Mankato, Minnesota, on 26 December, 1862.

As a child, he was kicked in the forehead by a horse.

He was an accomplished wrestler, who once ejected a violent troublemaker from a political meeting by throwing him 12 feet out the building.

He received so many death threats that he had a special file in his desk, marked "Assassinations", in which to keep them.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks