Divine Eagle: How much of a threat is China's new high-flying drone to US air superiority?

The US has led the way in the use of stealth aircraft in combat. Now the game could soon be up, as scientists in China and Russia are discovering ways to make the invisible visible. Mark Piesing reports

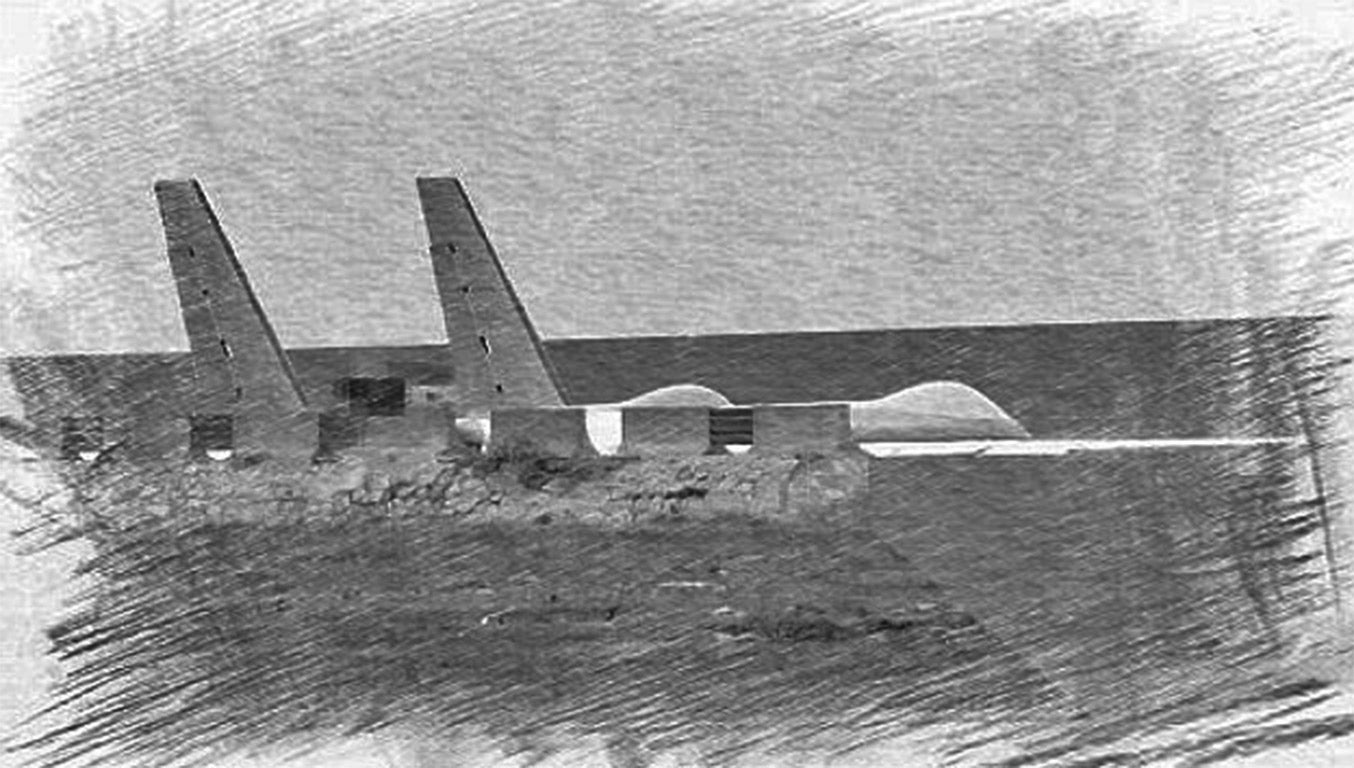

In May, grainy pictures emerged of a huge new twin-fuselage, high-altitude Chinese drone called the Divine Eagle. Those in the know instantly labelled it the "stealth-hunting drone". Stealth technology is the equivalent of electronic camouflage for planes, making them hard for enemy radar to spot – but the Chinese drone is certainly big enough to carry the special radars developed to detect stealth aircraft. It's able to fly high enough to detect them long before they can reach their targets. Its radar is rumoured to have been able to pick out an American stealth F-22 Raptor off the coast of South Korea almost 500km away.

To some analysts, the Chinese drone represents the death of stealth – for others, merely a serious threat to the future of the technology on which America has based its air superiority.

Stealth, or "low observable technology", is a combination of aircraft design, tactics and electronic countermeasures designed to make planes less visible to radar and other systems, which the US has pioneered. As well as trying to create the lowest possible radar signature by getting rid of the tail, it also tries to reduce things such as infrared emissions from the engine exhaust and electromagnetic emissions from the computers on board. Stealth tactics involve looking for gaps in air-defence systems.

When people think of stealth aircraft, they tend to picture the triangular black F-117 stealth fighter and B-2 bombers that penetrated Saddam Hussein's much-vaunted air defences at the start of both Gulf wars – or perhaps the troubled Lockheed F-35 Lightning stealth fighter programme on which the UK has gambled the future of its aircraft carriers. However, the Horten Ho 229 flying wing developed by the Nazis during the Second World War was probably the first. While the Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird spy plane used some basic stealth technology, the great leap forward in stealth really occurred in the 1970s with the Lockheed Have Blue project to develop a stealth fighter. This programme led directly to the F-117 and B-2.

However, success has a downside: your rivals begin to take stealth seriously and start the race to make the invisible visible. For some time the answer was a technology that the West had discarded but the Soviets had continued to develop – and which was responsible for the headline downing of a supposedly invisible F-117 in 1999 during the Kosovan conflict by the supposedly obsolete Serbian air defences.

"In reality, stealth planes are never completely invisible, as they will always generate a radar signature in the end," Douglas Barrie, senior fellow for military aerospace at the International Institute for Strategic Studies in London, says. "What you are trying to do is hold this moment off for as long as possible. If you are seen five miles from your target, compared to be being spotted 100 miles away, then it will have done its job.

"If there was a window when stealth fighters and bombers were undetectable, then it was when the F-117 had completely free rein with Iraq's poor old air defence; however, rivals such as Russia and China have over the past 25 years started to develop countermeasures, including radar that can pick up stealth planes."

Bill Sweetman, the editor-in-chief of Defense Technology International, part of the Aviation Week Network, argues that these kind of countermeasures are now "proliferating". Whereas most radars operate between 2GHz and 40GHz, a low-band equivalent such as VHF radar operates between 1MHz and 2MHz and is able to pick out most stealth planes that are known to be flying today. That's because the scientists realised that – while it can pick up "noise" such as clouds and rain, which was a reason why the West abandoned it – it does have basic physics on its side: its wavelength is the same magnitude as the prominent features on many stealth planes, so that its signal bounces back. The US military was warned about this then-theoretical vulnerability back in the 1980s.

"The Russians persevered with low-band radar due to their technological conservativism," Dr Igor Sutyagin, senior research fellow at the Royal United Services Institute, says. "And in the end they had great success."

"The most visible piece of counter-stealth in the past couple of years has been the public display – by both Russia and China – of VHF-Aesa radars," Sweetman says. Put simply, Aesa radars like those supposedly on the Divine Eagle drone are made up of a large number of solid state, chip-like modules that each emit an individual radio wave; these meet in front of the antenna to form a beam that can be easily aimed at a very specific target – and, combined with VHF, are an effective stealth-hunting tool.

"Big VHF radars were always known to be effective against anything other than a B-2 [which has no tail], but they had very large antennae that made them very cumbersome, with low scan rates," Sweetman says. "On the other hand, if an Aesa gets a hint of a detection, it can use electronic scanning to focus a lot of energy on the target."

The final trick is "to combine together different radars into an integrated air-defence system and a central information-processing centre that can make life very difficult for any stealth fighter or bomber", Sutyagin says. And stealth planes are not always stealthy from every angle (it costs too much money). So if you have radar in front, at the sides and above – with a high-altitude drone such as the Divine Eagle – along with satellite tracking of any target, then it might well be a case of RIP stealth.

However, it might not be game over yet. Not everyone has these capabilities and centralised air defences are also vulnerable to hacking, or even special forces. While one response might be to reduce the profile of the plane – using electronic warfare systems and stand-off weapons to increase survivability instead of stealth – there is, according to Sweetman, another option: develop weapon systems like that of the Dassault nEURon drone, which can be programmed to visually seek out large radar arrays.

Not yet, though, Sweetman says. "You can take stealth to the next level," he says, meaning a large, flat, tailless subsonic flying wing and active stealth technology. "In theory, by transmitting a signal just half a wavelength off the wavelength of the radar, your plane can disappear."

The US might have already reached the next level, even though the decision on its new stealth Long Range Strike Bomber is still some way away. In the end, says Barrie, "The US isn't standing still and we are continuing to spend significant amounts on classified programmes." Whether that is enough to keep stealth alive, only time – and war – will tell.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments