In an age of science and cynicism, what does the future hold for the professional astrologer?

As thoughts turn to what 2016 has in store for us, Sophie Morris talks to the people at the heart of the horoscope business

Hopeful as I am of finding a room full of crystal balls, smoke and mirrors, a visit to a class run by the London School of Astrology (LSA) yields nothing of the sort. Altogether 29 students sit in the bowels of the Quaker Friends House opposite Euston Station, a good attendance for a rainy Thursday evening in December. There are 25 women and four men – all but a handful look over 40 – sitting in rows at long tables, studying the astrological chart at the front of the room, and not a crystal or cloak in sight.

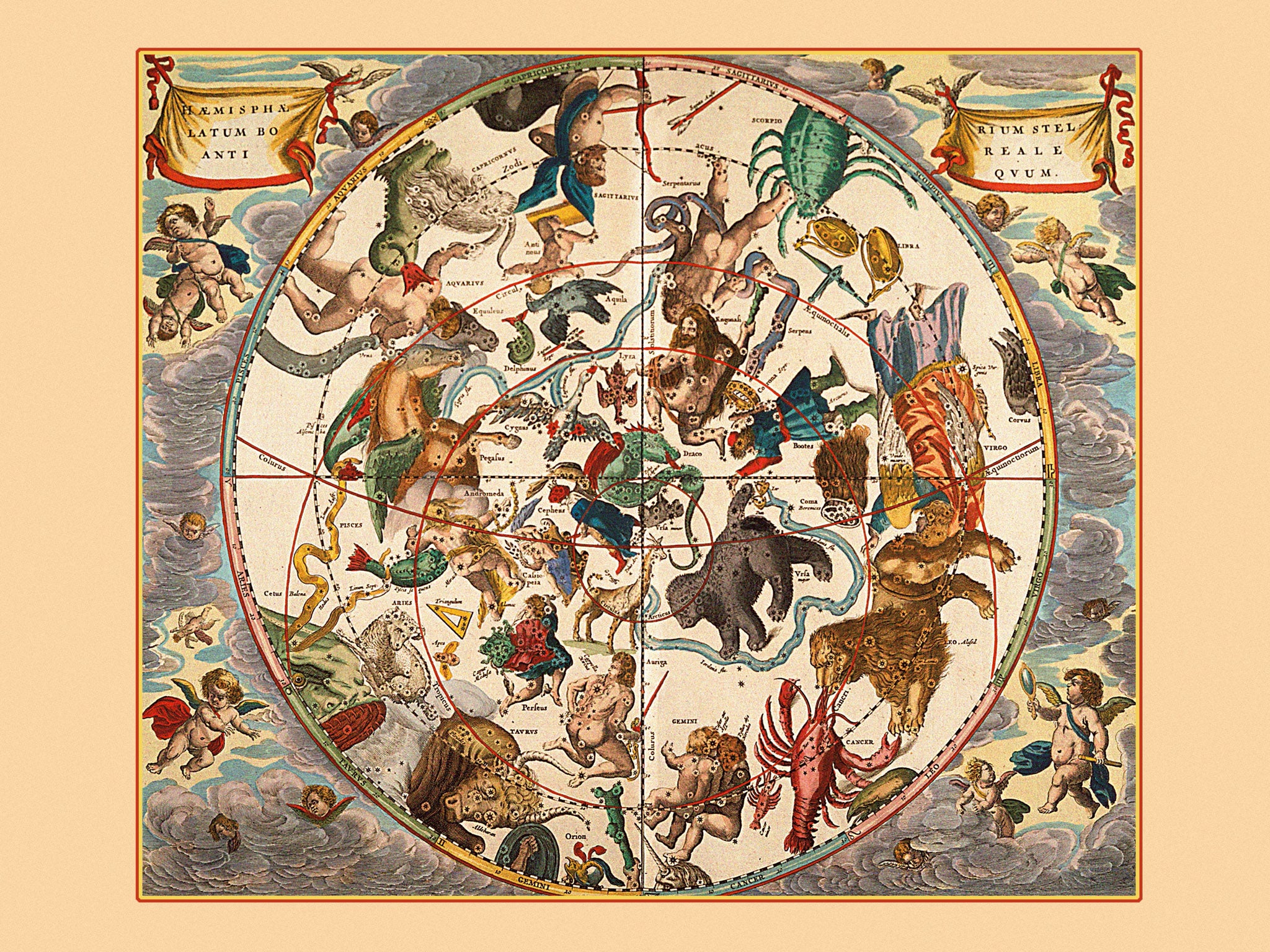

The chart is Gordon Brown’s. That’s to say it’s been established based on the time, date and location of the former Prime Minister’s birth. An astrologer’s first job is to draw up a client’s chart featuring the planets and signs of the zodiac, which their readings will be based on.

“If,” explains the teacher Frank Clifford, referring to the position of the planets on the circular illustration, “Gordon Brown had consulted an astrologer when making his deal with Tony Blair about handing over the leadership, we could have told him he’d be waiting for a very long time.”

Clifford is in his early forties but looks a decade younger. He’s wearing blue jeans, a black t-shirt and trainers. His long silver chain and goatee are borderline new-agey, but his most remarkable characteristic is his enthusiasm for astrology, which he’s been involved with since he was a teenager.

Now head of one of two schools in the UK still offering weekly face-to-face rather than correspondence or intensive residential courses ion the subject, he also writes books and acts as a media astrologer for a number of publications. Clifford has around 100 students studying foundation years or diplomas (three years) in astrology, costing from £690 a year for three terms of evening classes. The Advisory Panel on Astrological Education (APAE) lists 14 accredited member schools but not all offer regular classes.

Along with the LSA, the Faculty of Astrological Studies is the only school also running physical diploma courses. It currently has around 500 students across all its courses, who pay upwards of £285 per module to complete the eight diploma modules. Sharon Knight is chair of the Association of Professional Astrologers International (APAI). She tells me she has around 120 vetted astrologers, who have completed these types of diplomas, on her books.

Why bother to train, when anyone can declare they are an astrologer and start selling their services? There are fraudulent practitioners in all walks of life, but with astrology there’s no legal bar to reach, only an ethical one. Talking before the class, Clifford shares a classic astrology horror story. He met a woman in California whom he describes as an “emergency client”. She’d seen a vedic astrologer (Indian astrology, there are many kinds) who had told her she would die or lose a limb in an accident between two specific dates a few days apart. If she were to buy certain talismans from the astrologerhim however, he could work to reduce the effects of the coming trauma. “I can’t imagine anyone over here doing that,” says Clifford. “It’s about the power invested in the guru. We spoke about her giving her power over to others. I emailed her the day after the prediction and she did end up buying these things the vedic astrologer had recommended because she was scared. That made me feel sick, what an awful thing to be subjected to.

“Astrology is never really about advice, it’s about consultation or dialogue. I’d like people to learn a little bit before they get so critical. It’s not a belief system, it’s not a cult, it’s not a religion. It’s a way of looking at the world, it’s a language.”

Gordon Brown, as far as we know, did not consult an astrologer at the time of that now folkloric “Granita Pact”, nor is there evidence he ever has. We’d be surprised to learn that this unshowy politician looked to the heavens for insights and approval, but he wouldn’t be the first. John Major was reported to have consulted an astrologer while he was prime minister; David Tredinnick, serving Conservative MP for Bosworth, has said astrology could help our ailing NHS, and it’s no secret that astrologer Joan Quigley held as much sway over former US president Ronald Reagan as any of his official advisoers. According to Clifford, Quigley found ways for Reagan and Gorbachev to communicate, ultimately ending the Cold War.

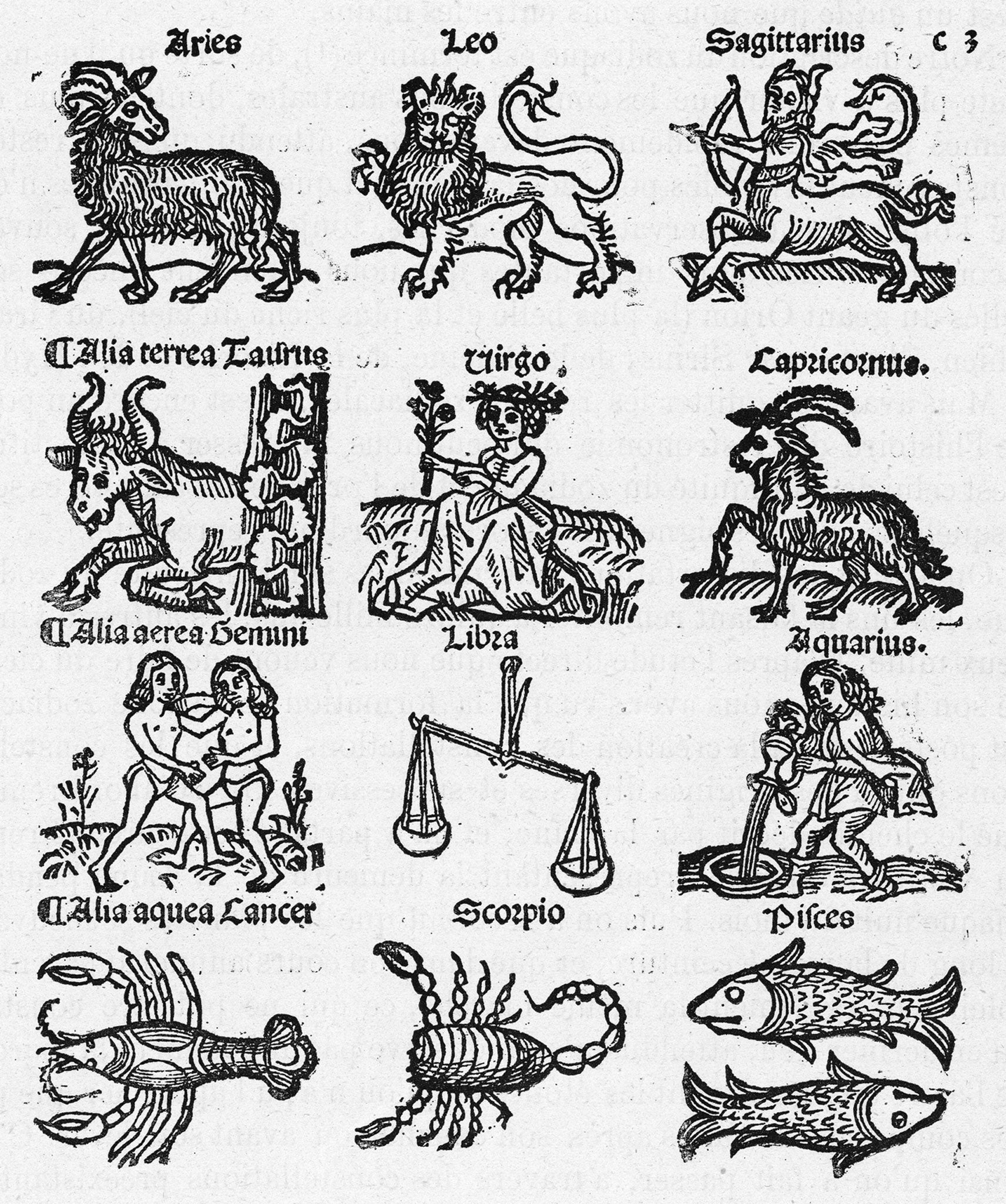

For a practice with ancient origins and a dubious premise – that the relationship between the planets and details about our birth can provide insights to our futures – astrology gets a lot of attention. Perhaps this is down to our desire, or desperation, to know the unknowable, and our fascination with gurus, leaders, divinators – anyone who might explain the inexplicable. It is also thanks to its popular accessibility through newspaper and magazine columns, a tradition which began in the 1930’s when astrologer RH Naylor wrote the horoscope of newborn Princess Margaret for the Sunday Express. The Daily Mail’s long-time astrologer Jonathan Cainer calls it “the oldest profession”, (“Long before anyone thought of charging for ‘that’, we were charging for ‘this’,” he claims).

To find the earliest written examples of astrology we need to go back to the second millennium BC, and most cultures have since been shown to have some ancient practice of interpreting events – often public events such as the weather, politics or war – by reading signs from the skyies. The astrologers I talk to emphasise that their job is not to “predict” the future, although much of their work involves “forecasting”, but to work with clients to see what hazards and opportunities may await them, and to provide guidance in how best to approach these life events. This contemporary strain of astrology is known as psychological astrology.

“Astrology is not deterministic,” says Cat Cox, president of the Faculty of Astrological Studies. “I think there’s a lot of confusion and misunderstanding about this in our culture.”

So if we can’t prove or disprove astrology by seeing predictions either play out or fail to materialise, how can we test it and trust it? “That question comes from our modern rational Western world view that deems what’s true is based on data and scientific results,” says Cox. “Astrology is a symbolic system, it doesn’t operate within that Western framework and our astrologers aren’t trying to demonstrate that. There are other ways to be in the world.”

Clifford alerts me to a famous quote by American financier JP Morgan: “Millionaires don’t use astrologers, billionaires do.” The banker Morgan was rumoured to have pulled out of his trip aboard The Titanic on advice from his astrologer.

Do we “play” astrology, much like we play the Lottery, in the hope of seeing untold billions in our futures? Remember Mystic Meg, the National Lottery’s in-house astrologer when it launched, with her crystal ball and spooky voice?

It is curious that while 97 per cent of us know our star sign (there is some controversy over calling zodiac or sun signs “star signs”, but it’s the most regular usage in the UK), according to a YouGov survey from July 2015, only 20 per cent of us believe star signs can tell us something about ourselves or another person. The survey also found that 8 per cent believe horoscopes can tell us something about the future, and 4 per cent have changed their behaviour based on something read in a horoscope.

Cainer is mindful of this 4 per cent, and subjects everything he writes to what he calls his “What if I was suicidal test” after a reader interpreted “If you’ve got something that’s big in your life go ahead and do it today” as a sign to kill himself, and did so.

As a business, Cainer – who has 30 staff and an annual turnover of £2mand 30 staff – says astrology is “recession-proof”. “The intelligentsia or chattering classes go through phases of liking or disliking astrology,” he says. “Most regular folk just like it and nothing much has ever changed, or ever will.”

There’s a clip on YouTube, some 20 years old, of a discussion between Cainer and Richard Dawkins, the scientist and polemic atheist.

“I take science very seriously,” begins Dawkins, dressed in a suit and speaking from BBC Television Centre. “I think science is a beautiful thing. I think astronomy is very beautiful. I think the universe is very beautiful. I think it is demeaning and cheapening to get ‘fun’ from this kind of thing.”

Cut to Cainer in a studio in Leeds, where he’s seated against a backdrop of tie-dye sarongs decorated in suns and stars, and wearing a waistcoat patterned with similar emblems. On a table in front of him are model planets, a novelty candle, and a huge book. He confirms to me he took his own props along that day.

The book turns out to be a dictionary, which he opens to look up the definition of “science”. “I don’t really know quite where we stand on science,” he says. “The point is, science is a word as far I understand it with quite a broad definition.”

This is the same argument that has dogged astrology through the 20th century and up to the present day. Really, it’s the same argument that has countered its veracity since the scientific revolution or emergence of modern science, which can be dated back to anywhere between the 16th century astronomy of Copernicus and Newton’s laws of motions and gravity, published towards the end of the 17th century. Several of the astrologers I talk to point out that their kind used to be revered as priests were, as if this provides credence. They point, too, to the significance of astrology in the story of the three wise men who travelled to visit the baby infant Jesus.

Those, like Dawkins, who believe in rational Western thought just cannot get their heads around the fact that musings based on the movement of the planets are printed alongside news stories, and intended as life advice. Even those who subscribe to other belief systems, such as Christianity, Islam and Judaism, people who are totally fine with the idea of a man walking on water and returning from the dead, even these people find it a bit far-fetched that here we all are, in 2016, planning out the day or the month ahead based on a few esoteric sentences pegged to our date of birth.

Since that BBC clip was filmed in the early 1990s, Cainer has moved on. “My Victorian and Edwardian predecessors were very keen to declare that astrology was some kind of a science,” he says. “Of course it isn’t and it can’t be, and it’s ludicrous and preposterous that anyone ever claimed that astrology was scientific. But it is based on measurable accurate astronomical information, and you can’t deny that.”

The physicist and television presenter Professor Brian Cox has also spoken out against astrology, describing it as “rubbish”, while Dawkins once asked in the Independent on Sunday, “If astrologers cannot be sued by individuals misadvised, say, into taking disastrous business decisions, why at least are they not prosecuted for false representation under the Trade Descriptions Act and driven out of business? Why, actually, are professional astrologers not jailed for fraud?”

Dawkins is one member of what Cainer enthusiastically describes as an “unholy alliance” of atheists, sceptics and humanists who, he says, are “making up for lost time by exerting their wrath equally on religions and on any people who claim to have some sort of a relationship and an understanding of the mind of the divine.”.

“I think they get so worked up about it because it’s almost like the lid has come out of a bottle of repression which has been in place for centuries. Intellectuals, free thinkers, intelligent individuals around the world have had years of having to bite their tongues while the most unutterable crap is recited as if it’s indisputable truth. So now they’re getting a bit slap-happy.

“Unfortunately, knocking established religion is not fashionable or popular at the moment, so here’s something you can take a pop at – you can take a pop at those stupid ignoramuses who are moronic enough to believe that the movements of some tiny items of rock and ice, thousands or millions of miles away from the eEarth, could have any relationship with events on planet Earth. It’s preposterous. It’s unproven and it’s more than unproven, it’s unprovable.”

Cainer has been with the Mail since the early 1990s except for a brief sojourn over at the Mirror. Shelley von Strunckel’s horoscopes appear in the Evening Standard and The Sunday Times. She says they feed our hunger for inner peace. She was the first astrologer to have a column in a broadsheet paper, The Sunday Times, when Andrew Neil hired her in 1992. Today Catherine Tennant writes in The Daily Telegraph, and the mid-market and red-top tabloid papers run horoscopes, as do a good number of the women’s weeklies and monthlies, but The Independent on Sunday dropped its horoscope, which was a spoof anyway, some time ago, as did The Observer.

Cainer’s strand of astrology is known as star or sun or zodiac sign forecasting. We know it as horoscopes. Von Strunckel and Cainer acknowledge that their work – to distil astrological readings into around 50 words and confined to the 12 signs of the zodiac – is limiting, but both see their regular newspaper columns as a gateway to readers’ deeper exploration of astrology.

If the noose is tightening around astrology in contemporary Western society, it is claiming fresh blood in other parts of the world. Cat Cox and Sharon Knight both attended adult education classes in astrology in the 1980’s, but these no longer exist.

“In the sanitised West astrology has declined dramatically,” claims Knight, but in eastern Europe, Turkey, India and China, business is booming. Cainer and Von Strunckel’s columns are syndicated around the world, with Cainer translated into Spanish and Japanese, while Chinese Vogue enlisted Von Strunckel for its launch in 2005 and she remains their resident astrologer. “It’s particularly in Britain that the climate has turned colder,” confirms Cainer. “It hasn’t affected business, but I’m getting more online trolling.” Von Strunckel says she isn’t subject to online abuse.

I find my Pisces mug at the back of a cupboard. How comforting to read that I am “imaginative, sympathetic, dreamy, sentimental, artistic and temperamental” – characteristics the mug attributes to all Pisceans.

“It’s a very two-dimensional picture to say to someone you’re a typical Cancerian or a classic Gemini,” says Cainer. “Nobody really is. Everybody is an individual with a full and complex tapestry of characteristics within their personality.”

To demonstrate this, I ask him to provide some more detail, and he creates my “Personal Profile”, a 25-page document containing my individual chart and guidance on what this may mean for me in general, along with a “Guide to the Future 2016”, which runs to 85 pages of commentary on situations I may, or may not, encounter over the coming 12 months. He charges £24.95 and £29.95 respectively for these services on his website.

For a layperson these charts don’t make the easiest reading. Here is one example of several hundred I have to work with for the year ahead:

You will first start to notice the effects of this transit around 13th September 2016. You will continue to experience this influence until 15th September 2016 after which time it will rapidly diminish. Great singers are forever insisting that, for the sake of something they love, believe in, or wish to honour,, they will ’“climb the highest mountain or swim the deepest sea.’” Perhaps they really would but it is hard to envisage. It is also hard to see why they would need to.

In life, we are far more likely to face some far less exciting challenge. Could you; sit through a hundred meetings, wait at a thousand bus stops, or wash a million dishes? That’s the true test of your current fantasy. Assuming, that it’s an inspiring one. If it’s a fearful fantasy that you keep entertaining now, the advice is even more simple and straightforward. Ignore it. It means nothing.

A million dishes? I’ll have to discuss this with my husband, because he does all the washing up, with the help of a dishwasher. But if 2016 has me waiting at a thousand bus stops – that’s three a day – I’ll wager there’s something off about this whole business. Or else it’s time to buy a car.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments