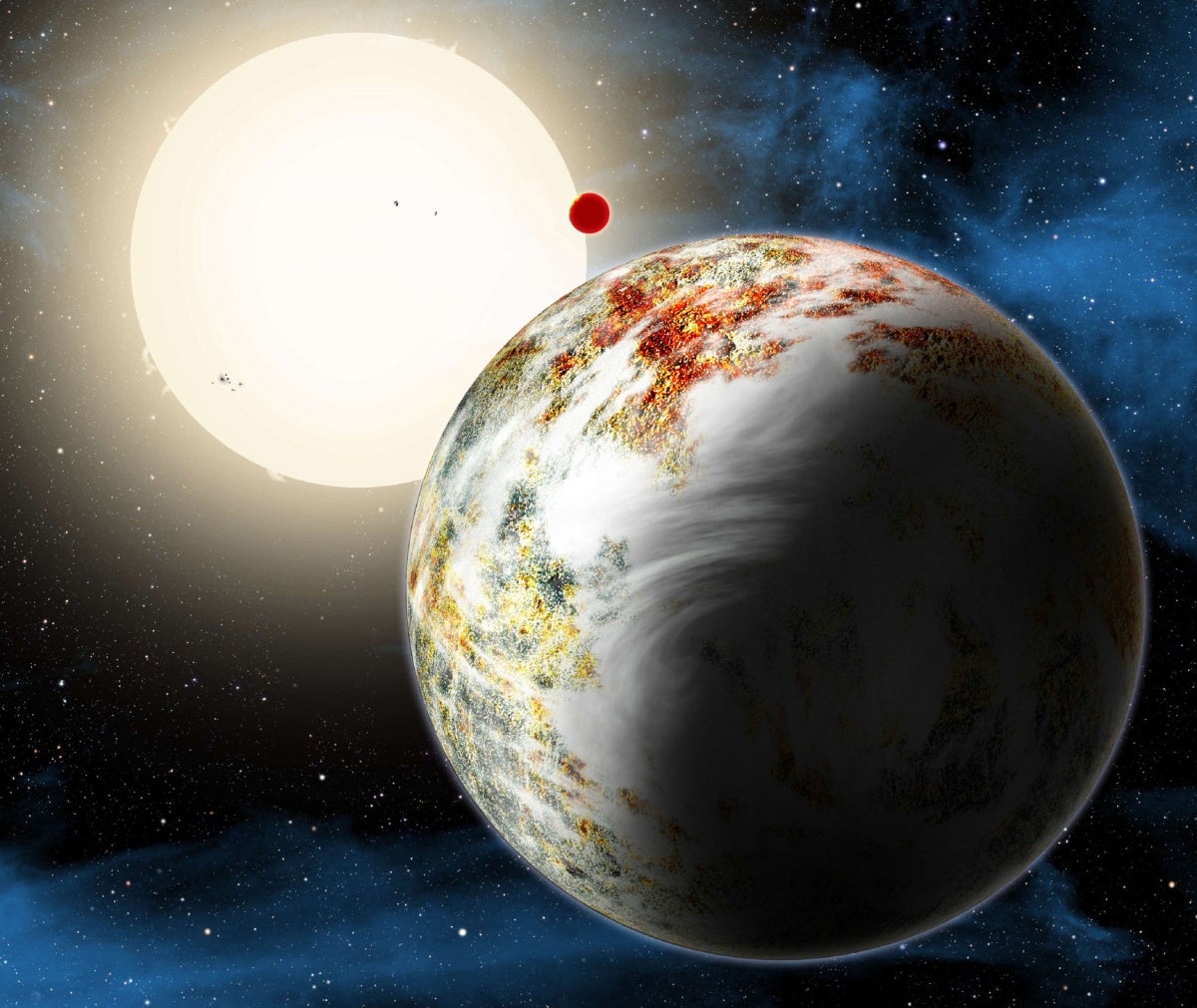

Kepler-10c : Scientists discover 'mega-Earth' with a density 17 times that of our planet

Planet orbits a sun-like star about 560 light-years away

A massive rocky planet twice the size of Earth has been discovered, which if it has an atmosphere could have a cool enough surface to support life.

Named after the Kepler telescope through which it was spotted, as is the convention, the planet has a hard surface which is unusual for one of its size, as usually they draw in hydrogen and become gas giants like Jupiter and Neptune.

The discovery has left scientists scratching their heads, even being given the nickname the 'Godzilla of Earths'.

"The proper way to call it is something bigger than a 'super-Earth, so how about 'mega-Earth," Prof Dimitar Sasselov, of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, told reporters, later opting for the phrase, "the Godzilla of Earths!".

Orbiting a star about 560 light-years away alongside a lava world called Kepler-10b, the planet is roughly twice the size of Earth but way more massive.

"It's 17 - in fact, it's more than 17 - Earth masses, and that brings the density to 7.5 grams per cubic centimetre, which is a lot more than what we know of rock here on Earth (5.5g/cm3)," Prof Sasselov added.

"But remember, this is a very massive planet, which means those same minerals are highly compressed."

"So, what you see in the density is mostly due to compression rather than different composition. The composition comes out as being a combination of rocks and some volatiles, probably 5-15% at most of water."

The hard surfaced planet of course drives us to question whether it could, or could have supported life (as we know it), which is dependent on whether it has an atmosphere and clouds.

"It is [on] solid planets that is the place, as far as we know - and we know very little about the origins of life - where we think the chemistry is capable of building those molecules that lead to the emergence of life from geochemistry," Prof Sasselov said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks