Steve Connor: Genetic testing can predict but not cure

Lab Notes

Huntington’s disease is a relatively rare genetic disorder that you wouldn’t wish upon your worst enemy. If you carry a single copy of the affected gene you are destined to die a horrible death involving uncontrollable movements, psychiatric disturbances and progressive dementia.

The first symptoms typically occur around the age of 40, and it takes between 10 and 15 more years for the gradual neurodegeneration to end life. Ten years after the excitement of mapping the human genome, and the revolution in the understanding of genetic disorders that the achievement has brought, it is easy to forget that some of those directly affected by inherited diseases have seen little in terms of practical benefit.

The gene involved in Huntington’s disease was mapped to chromosome 4 in 1983 by a team led by Jim Gusella at Harvard Medical School in Boston, but it took another 10 years of intensive effort to isolate and clone the gene itself. This allowed scientists to find the type of changes, or mutations, that cause the disorder – the mutated gene has about two or three times the normal number of ‘GAG repeats.

I remember on both occasions – in 1983 and 1993 – there were optimistic predictions that the discoveries would soon lead to a test for the carriers of the Huntington’s mutation and effective treatments – even possibly a cure – for the disease. The sad fact is that although a relatively cheap and accurate diagnostic test for the Huntington’s mutation has existed for some years, this medical advance has for the affected families arguably produced more misery than it has eradicated. For a start, there has been no accompanying revolution in treatment, largely because there are so few affected people (estimated to be about 12,000 in Britain) to make it worth the expense and effort of the drug companies to develop new therapies.

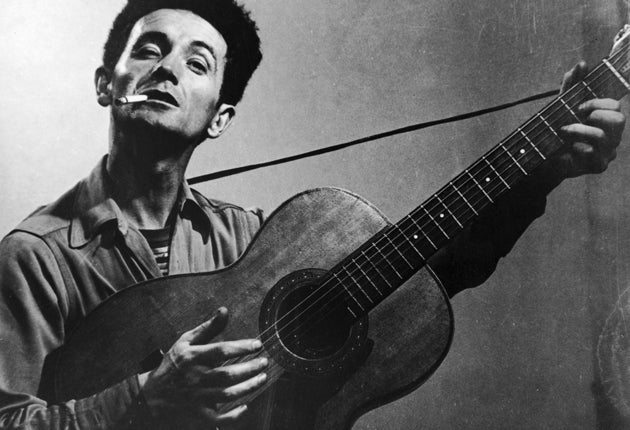

Secondly, although there is a moratorium in Britain on having to inform insurance companies of the result of such genetic tests, Huntington’s disease is the single, shameful exception. If you have had the test, and are a carrier of the mutation, you are obliged to tell any insurance company who asks for the result. This will come as little surprise to anyone with a passing interest in the history of this disease, which has affected several prominent people, such as the American folk singer Woody Guthrie, who died of the disease in 1967. Huntington’s disease is mired in stigma and prejudice. Early studies of it in the 20th century linked it with witchcraft, and it became a model for the sort of genetic disease that the eugenics movement wanted to target with programmes of compulsory sterilisation. Even today, many affected families prefer to keep their affliction secret because of the perceived stigma attached to it – it is believed that many people request for it not to be put on death certificates.

Alice Wexler was in her early twenties when her mother died of Huntington’s disease and she had no idea that her maternal grandfather and three uncles had also died of it – such was her mother’s sense of shame. Wexler, an historian who has written on Huntington’s, is closer to the science of the disease than are many other members of affected families. Her sister, Nancy Wexler, was part of the Gusella team that discovered the gene. Yet even Alice has declined to take the genetic test (although given her age she appears thankfully to have escaped the worst).

Indeed only 20 per cent of people at risk of Huntington’s actually decide to take the gene test. The reason for this low take-up is quite simple: if you carry the mutated gene there is little you can do about it. Why take the test, especially, if it will do nothing but affect your insurance cover? In the euphoria over the revolutionary advances in the brave new world of genetic medicine, we must remember that, for many people, science in the free-market world of drug development has yet to live up to expectations. Huntington’s disease remains a painful reminder that scientific advances do not always offer practical benefits.

***

As exclusively predicted by this column last year, the Royal Society has confirmed that its next president will be Sir Paul Nurse, Nobel laureate and currently president of the Rockefeller University in New York. Sir Paul is one of those rare scientists whose brilliance has not gone to their head. He will make a good PRS - president of the Royal Society.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks