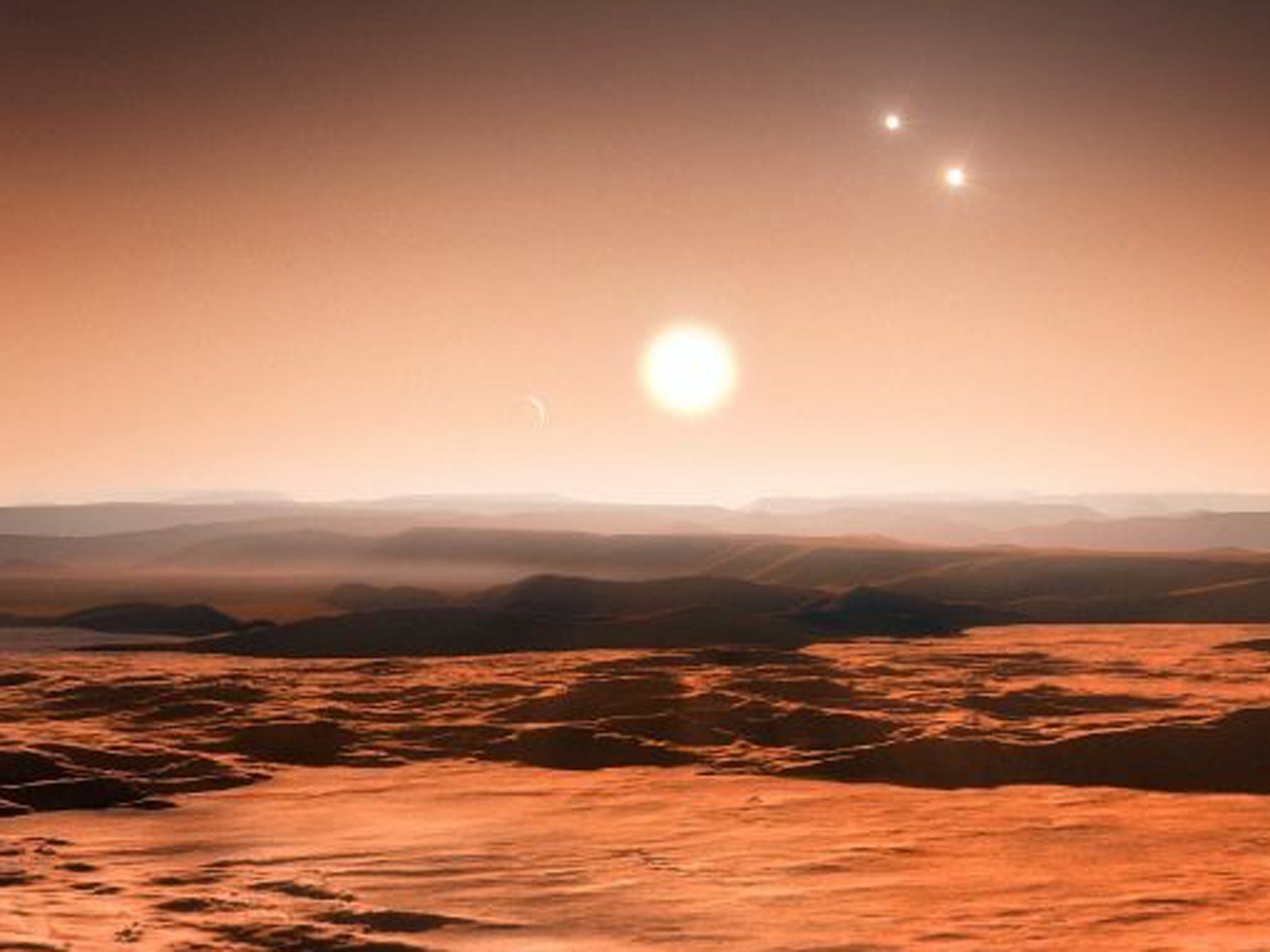

Three 'super-Earths' discovered: Are planets found orbiting Gliese 667C in nearby solar system capable of supporting human life?

They orbit Gliese 667C, one of three stars 22 light years away in the constellation of Scorpius

A nearby solar system is packed with up to seven planets including three "super-Earths" that may be capable of supporting life, say scientists.

The planets orbit Gliese 667C, one of three stars bound together in a triple system 22 light years away in the constellation of Scorpius.

Astronomers believe they fill up the star's "habitable zone" - the orbital region just the right distance away to permit mild temperatures and liquid water.

Three of the new worlds are categorised as "super-Earths", meaning they have between one and 10 times the mass of the Earth.

If like the Earth they are rocky and possess atmospheres and watery lakes or oceans, they could conceivably harbour life.

Because Gliese 667C is part of a triple system, anyone standing on one of the planets would see its two companions as very bright daylight stars. At night, the companion stars would shine as brightly as the full moon on Earth.

Previous studies had identified three planets orbiting the star, including one in the habitable zone.

The other planets were discovered after astronomers revisited previous data and made new observations using a range of telescopes.

Lead scientist Dr Guillem Anglada-Escuda, from the University of Gottingen in Germany, said: "We identified three strong signals in the star before, but it was possible that smaller planets were hidden in the data.

"We re-examined the existing data, added some new observations, and applied two different data analysis methods especially designed to deal with multi-planet signal detection. Both methods yielded the same answer: there are five very secure signals and up to seven low-mass planets in short-period orbits around the star."

Gliese 667C is smaller, fainter and cooler than the Sun, having just over a third of its mass. As a result its habitable zone - where conditions are warm but not scalding hot - is relatively close in.

This is helpful to astronomers because the limits of current technology make it hard to detect smaller Earth-like planets in more distant orbits.

The astronomers believe the star's habitable zone is full - there are no more stable, long-lived orbits available within it that could contain other planets.

If the Earth circled the Sun at the same distance it would be far too hot to support life. But much milder conditions may exist on planets orbiting close to dimmer, cooler stars such as Gliese 667C.

Since low-mass stars make up around 80 per cent of the stars in our galaxy, the Milky Way, astronomers hope they might provide a rich harvest of other potentially habitable close-orbiting planets.

"The number of potentially habitable planets in our galaxy is much greater if we can expect to find several of them around each low-mass star," said co-researcher Dr Rory Barnes, from the University of Washington in the US. "Instead of looking at 10 stars to look for a single potentially habitable planets, we now know we can look at just one star and find several of them."

The findings, released by the European Southern Observatory, are to appear in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Although the planets are far too small to see with a telescope, they could be detected by looking for the effect of their gravity on the star.

The gravitational "tug" of an orbiting planet makes a star "wobble" which in turn causes its light wavelength to fluctuate. By measuring these tiny changes astronomers can calculate the planet's orbit and mass.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks