New genetic map of Britain shows successive waves of immigration going back 10,000 years

White indigenous English people share about 40 per cent of their DNA with the French

A remarkable new map of Britain shows how the nation was forged by successive waves of immigration from continental Europe over 10,000 years since the end of the last Ice Age.

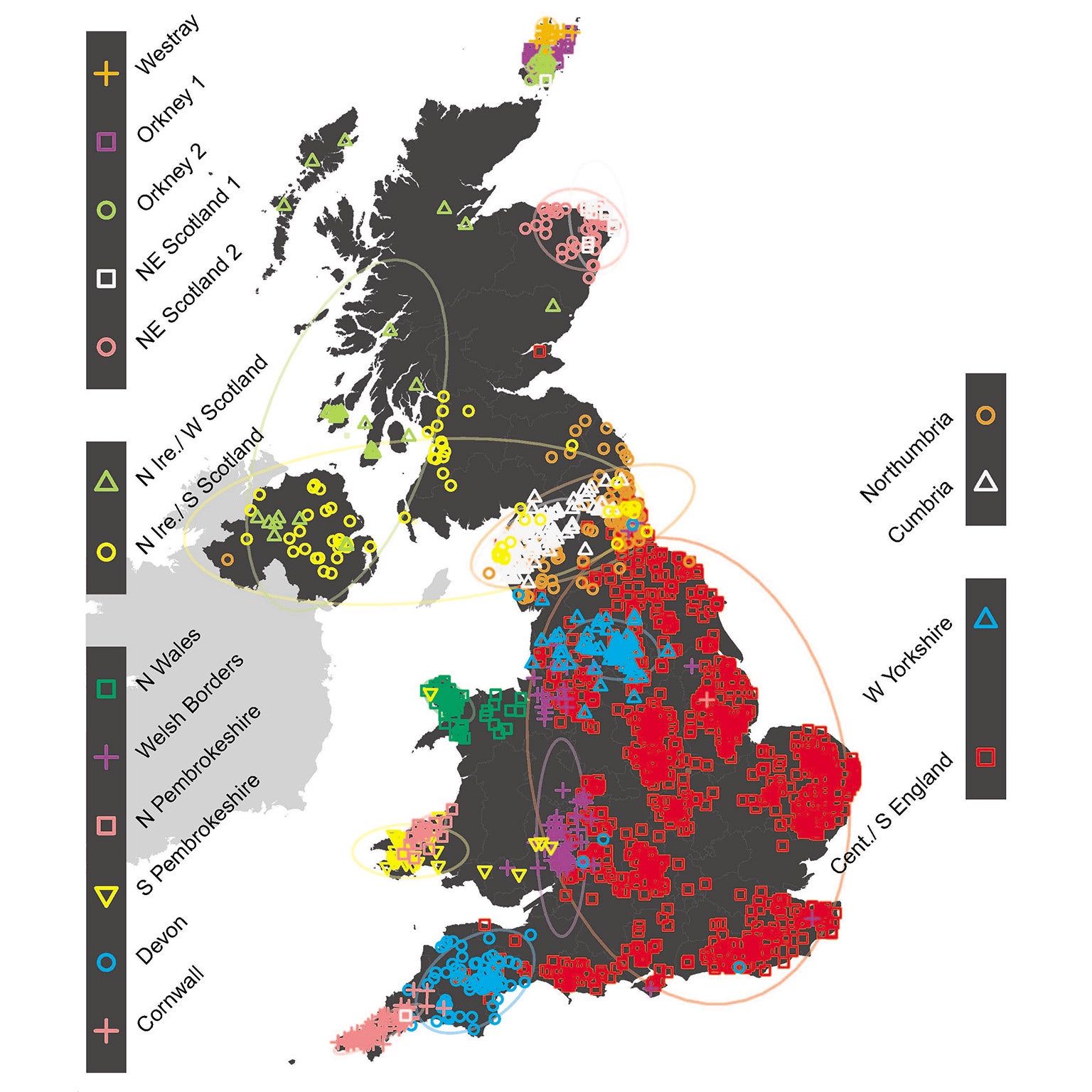

The map was drawn up by analysing the DNA of more than 2,000 people whose four grandparents had all been born in the same locality. It is the most detailed and far-reaching genetic analysis of the original inhabitants of these isles.

It reveals that the white, indigenous English share about 40 per cent of their DNA with the French, about 26 per cent with the Germans, 11 per cent with the Danes and in the region of nine per cent with the Belgians.

Geneticists and historians collaborated closely on the 10-years project and have been astonished to find that patterns in the DNA of Britons living today reflect historical events going back centuries, and in some cases millennia.

The genetic map shows 17 clusters of similarities in the DNA of modern-day people that echo major moments in history, such as the collapse of the Romano-British culture in the 5th Century and the subsequent rise of the Anglo-Saxons, and the Norse Viking invasion of the Orkneys in the 9th Century.

It also reveals much older movements and separations of people, such as the ancient ancestry of the Celtic people of North Wales who are probably descended from some of the oldest inhabitants of Britain, and the clear genetic division between the people of Cornwall and Devon that still persists along the county boundary of the River Tamar.

“It has long been known that human populations differ genetically, but never before have we been able to observe such exquisite and fascinating detail,” said Professor Peter Donnelly, director of the Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics at Oxford University.

“By coupling this with our assessment of the genetic contributions from different parts of Europe we were able to add to our understanding of UK population history,” said Professor Donnelly, one of the lead authors of the study published in the journal Nature.

One of the most intriguing signatures seen in the genetics of present-day English is the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons from southern Denmark and northern Germany after the end of Roman rule in 410AD. The DNA samples showed this migration involved intermarriage with the Romano-British Celts rather than wholesale ethnic cleansing, as some historians have suggested.

“The results give an answer to the question we had never previously thought we would be able to ask about the degree of British survival after the collapse of Roman Britain and the coming of the Saxons,” said Professor Mark Robinson, an archaeologist at Oxford University.

“This has allowed us to see what has happened. The established genetic makeup of the British Isles today is reflecting events that took place 1400 years ago,” Professor Robinson said.

Other major events in history, such as the Roman invasion and occupation between 43AD and 410AD, the large-scale invasion by the Viking Danes in 865AD and the subsequent establishment of Danelaw, as well as the Norman invasion of 1066, cannot be seen in the genetic profiles of Britons today.

This probably reflects the fact that often major cultural shifts are carried out by relatively few people within an elite who do not leave their genetic mark on the conquered masses, said Sir Walter Bodmer, the veteran population geneticist who first had the idea of the study.

Most soldiers serving under Rome who came to Britain were in any case more likely to be recruits from Gaul and Germany rather than being born in Italy, Sir Walter said.

“The people of the British Isles study gave us a wonderful opportunity to learn about the fine-scale genetic patterns of the UK population. A key part of our success was collecting DNA from a geographically diverse group of people who are representative of the location,” Sir Walter said.

“It was not a simple problem to get so many samples. It’s an extraordinary result and one that has provided a lot more than I had expected,” he added.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments